Sacked and silenced for being pregnant

- Published

"I was made redundant four months into my maternity leave.

"I was the bread winner, I had no legal cover and so was advised to sign a 'hush agreement', I felt I had no choice."

These are the words of a mother who contacted the BBC after we published our article about greater rights for pregnant women at work.

Her story - and those of others - suggests that discrimination continues at some of Britain's companies where senior managers flout the law to put pressure on women who become pregnant.

But the victims are too scared to speak out because they've been forced to sign non-disclosure agreements.

In some cases, the gagging orders even warn them about speaking 'anonymously' about their treatment.

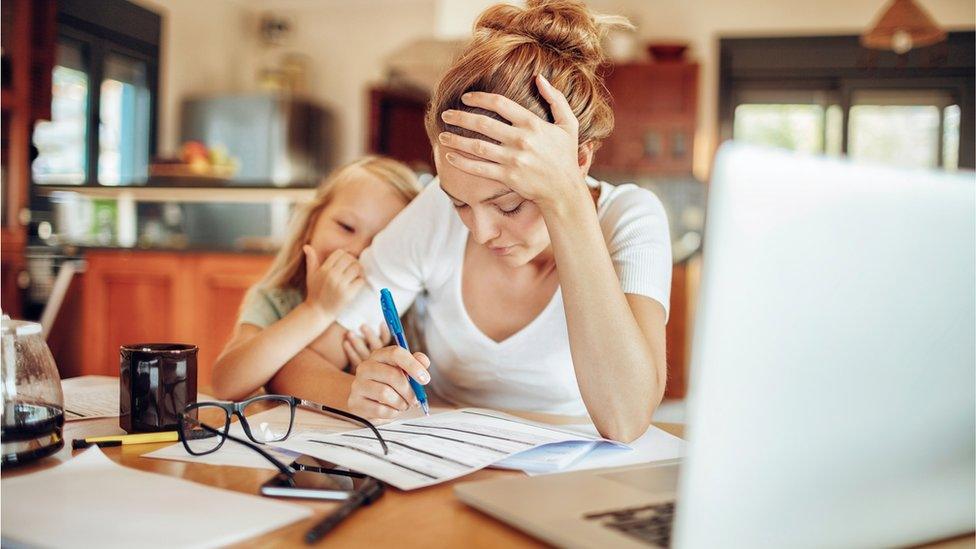

Stressful time

"It effectively allows companies to break the law," the mother who got in touch with the BBC said.

"You need a very strong case to succeed in court as well as needing a lot of tenacity.

"I had a newborn baby to focus on and the worry of paying the mortgage so couldn't fight the case.

Nearly five years on, she said: "Please don't publish my name, I just needed to tell my story. I want the law to change. It does not protect women at all."

The law is clear: it is illegal to make someone redundant due to pregnancy or maternity.

Yet women are still being badly treated, a point that was conceded last week by Business Minister Kelly Tolhurst, who said: "Pregnancy and maternity discrimination is illegal, but some new mothers still find unacceptable attitudes on their return to work which effectively forces them out of their jobs."

Another woman whose baby is only a few months old also contacted the BBC but, once again, only if she could remain anonymous.

Her problems began with a new senior manager at her workplace, she said.

"He called me in to have a discussion about my future and career goals and all seemed very positive. But after I told him I was pregnant his attitude completely changed. He just didn't speak to me after that, which was very odd."

When she was on maternity leave last year she put in an an application for flexible working but was shocked when it was turned down.

"They chose the wrong person with me. I know my rights and am very stubborn so I took it to appeal.

"The company offered a settlement which my lawyer advised me to accept, but it meant I had to sign a non-disclosure agreement."

She feels very bitter now. "I just felt like there was no empathy or understanding of my situation.

"To make matters worse, my husband has just had his application for flexible working turned down by his employer. It means we have to rethink our plans which we made based on our rights."

She said the government should do more to publicise people's rights at work and encourage people to speak out about being treated badly.

'Buying silence'

Campaigner Joeli Brearley, founder of Pregnant Then Screwed, which aims to support and promote the rights of mothers suffering discrimination at work, said: "NDAs are being used regularly to hold employees to ransom. They are a way of an employer buying an employee's silence."

She is campaigning for the use of NDAs to be monitored.

"You can't ban non-disclosure agreements as, in some cases, they do benefit the victim. The employer is prohibited from bad-mouthing the victim to potential future employers, and without NDAs there would be little reason for the employer to settle before court."

However, Ms Brearley believes that monitoring NDAs would help stop them "being used by employers to mask abhorrent behaviour".

She wants all NDAs to be reported to an independent body which has jurisdiction to investigate and act if it has concerns.

'Draw a line'

Phil Allen, employment law specialist at law firm Weightmans, also said NDAs could "benefit both parties".

Employees often wanted to "exercise some control" over what future employers would be told and to prevent them being told that a settlement or complaint existed. "Frequently, they also often want their colleagues to be told something positive," he added.

"Employers usually want the terms of exit to be confidential because they don't want other employees knowing that an exit package may be available, or because they want the agreement to permanently draw a line under a dispute."

And he said settlement agreements could not be used to stop someone making a "public interest disclosure".

"They also should not be used to stop issues being raised with the police or a regulator. Employees are also usually permitted to tell members of their immediate family in confidence."

What are NDAs?

Sometimes known as "gagging orders" or "hush agreements". In employment law, they're parts of contracts, or sometimes standalone contracts, between employees and companies. They typically prevent staff and ex-staff making information public. In legal practice they are often described as "confidentiality clauses", but are better known to the public as NDAs.

They can apply to commercially sensitive details such as inventions and ideas, or anything likely to damage an organisation's reputation.

If someone breaches an NDA, they break a contract, leaving them open to being sued.

But if a company thinks the NDA is going to be breached, it can apply for an injunction.

If someone breaches an injunction, this is a criminal offence, and can lead to a fine or jail for those found guilty.

In the US, it's thought that a third of workers have signed NDAs but, according to Marc Jones, a partner at IBB Solicitors, it's "impossible to say" how widespread they are in the UK.