Rent control: Does it work?

- Published

The claim: The arguments for rent control are overwhelming.

Reality Check verdict: It has been helpful for existing tenants in areas with particularly fast-rising rent, but it can be at the expense of new renters. In some places, it has also led to a shortage of supply. While the arguments for rent control are not overwhelming, it is possible that a well-designed policy combined with significant new homebuilding could be effective.

Mayor of London Sadiq Khan has called for a range of measures to help renters in the capital, including rent control.

He conceded that as mayor he does not have powers to regulate the rental sector,, external but said that he would lobby the government to implement rent control.

Rent control refers to a variety of ways in which the amount that landlords are allowed to charge may be limited.

Deputy Mayor James Murray told Reality Check that he and Westminster North MP Karen Buck would be taking time to look at a package of measures and said, that in addition to rent control, London needs to build a lot of affordable housing.

He added that there are already plans, external to build 11,000 council homes at social rent over the next four years.

Standard economic theory is that rent control does not work, because if you force rents down, landlords may decide not to rent out their properties, which reduces the amount of rental property available. So, what has happened in cities that have introduced it?

San Francisco

Research conducted at Stanford University, external looked at the impact of the expansion of rent controls in San Francisco in 1994.

The city had originally introduced controls in 1979, which covered buildings with five or more apartments but excluded new-build properties.

In 1994, this was expanded to cover any building with more than one household, but still excluded new-builds.

The researchers, led by Prof Rebecca Diamond, found that between 1994 and 2010, people who were living in rent-controlled properties had benefited from lower rents by about $2.9bn (£2.2bn) between them.

But they found that, coincidentally, renters who came to the city later paid an extra $2.9bn in higher rent over the same period, largely because of a shortage of available housing.

So the expansion of rent control had, in effect, been a transfer of money from newer (generally younger) renters to ones who had been living in the city for longer (and were generally older).

Researchers also found that the controls helped accelerate gentrification, because some landlords demolished their older properties in favour of new-builds, which were exempt from the limits.

Prof Diamond concluded that what is needed is a form of rent control that means the landlords do not have to pay for all of it, such as government subsidies or tax credits, to help renters absorb price increases.

There were demonstrations against high rents in Munich last year

Germany

Another example of rent control often cited is Germany, which has one of the lowest home ownership rates in Europe at 51%.

In Berlin there are about 1.9 million homes, of which about 1.6 million or 85% are rented, external.

Under the rules introduced in 2015, landlords in 313 of the 11,000 towns and cities in Germany (home to about one-quarter of the population including Berlin and Munich) cannot set rent for new tenants any higher than 10% above the local average from the previous four years. Existing tenants benefit from similar limits.

But, again, there are exemptions for newly-refurbished properties and those being rented out for the first time.

Research from the German Institute for Economic Research, external (DIW) found that the measure had worked in areas of Germany, such as parts of Berlin, that had experienced the biggest increases in rental prices, with rises of at least 4% in each of the previous four years.

But, in other areas subject to rent controls, it had not had the same effect.

Susanne Marquardt, from the Berlin Social Science Centre, told the BBC that rent control and stronger rights for tenants had balanced the needs of landlords and tenants for decades and helped encourage long-term thinking by both landlords and renters.

But she warned that "things have changed now as international investors come to the country and see real estate investment opportunities".

This problem involved the loopholes in the system. For example, a landlord may decide to do renovation work on a property and require the existing tenant to pay increased rent of up to 11% of the total cost of the work each year. This can be done without the consent of the renter and has been used to get rid of tenants who could not afford it.

The researchers from DIW suggested that the solution would be only to impose rent controls in the areas with the fastest-growing rents.

London

So what does this tell us about London?

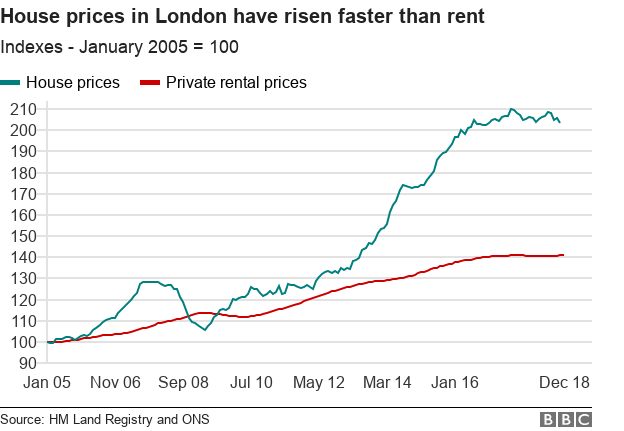

Rent is high in London, although it has not been rising as fast as house prices and average private rent has barely changed in the last two years.

The chart above shows how much rent and house prices in London have risen from a starting point in 2005.

Gemma Burgess from Cambridge University's Centre for Housing & Planning Research, points out that the example of cities such as Berlin, where landlords tend to be institutions that own lots of properties, may not be applicable to London.

"The overwhelming majority of landlords in England own one property," she says.

Her department conducted research for the London Assembly in 2015,, external which found that minor rent control measures such as a three-year freeze on existing private rents, would not make much difference to affordability.

However, it said that more radical measures, such as a cap on private rents set at two-thirds of their current market value, could lead many landlords to sell their properties.

She concludes that it will be difficult to find a policy that works. "I'm very dubious that rent control could help tenants and not reduce the stock of rental properties," she says.

"You need to significantly increase supply before you look at rent control."

- Published12 December 2018

- Published24 September 2018

- Published11 May 2018

- Published17 April 2018

- Published30 September 2017