UK employment at highest since 1971

- Published

- comments

The number of employed people in the UK has risen again, to a new record number of 32.7 million people between November and January, figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) show., external

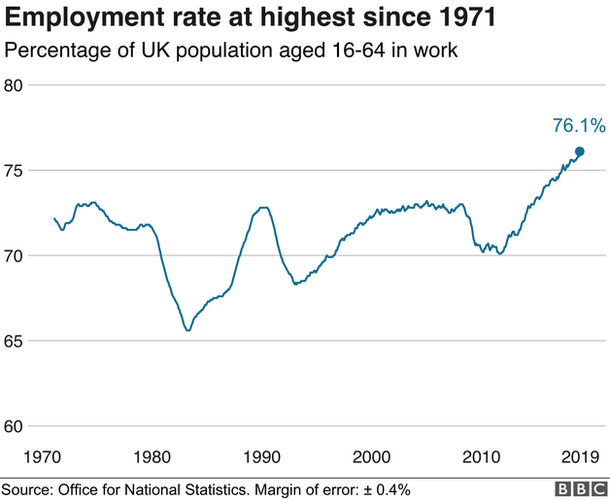

The 76.1% employment rate is the highest since records began in 1971.

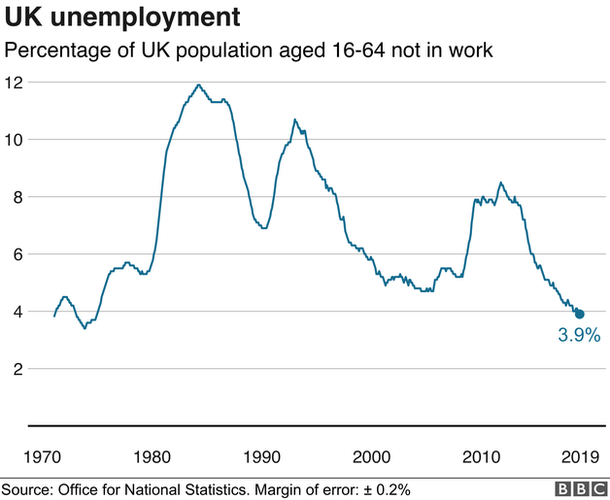

Unemployment fell by 35,000 to 1.34 million in the period, putting the rate below 4% for the first time since 1975.

The figure is 112,000 lower than a year ago, giving a jobless rate of 3.9%, well below the EU average of 6.5%.

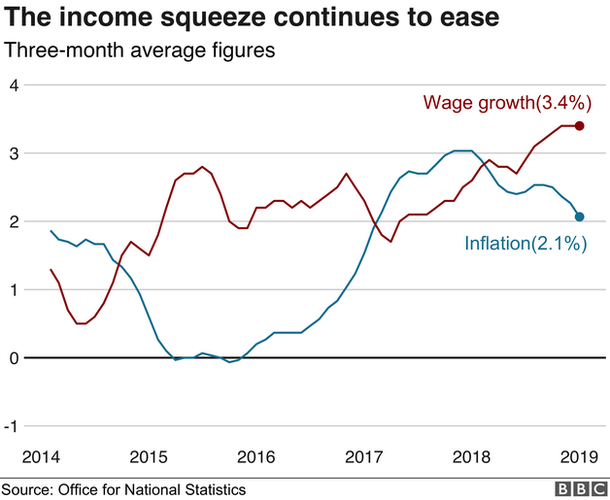

Average weekly earnings, excluding bonuses, were estimated to have increased by 3.4%, before adjusting for inflation, down by 0.1% on the previous month but still outpacing inflation.

ONS senior statistician Matt Hughes said: "The employment rate has reached a new record high, while the proportion of people who are neither working nor looking for a job - the so-called 'economic inactivity rate'- is at a new record low."

Employment Minister Alok Sharma said: "Today's employment figures are further evidence of the strong economy the chancellor detailed in last week's Spring Statement, showing how our pro-business policies are delivering record employment."

Where are the new jobs being added?

The number of men in employment increased by 77,000 to a record high of 17.32 million.

The number of employed women rose by 144,000 to a record high of 15.40 million - the largest increase since February-to-April 2014.

The UK's highest regional employment rate was in the south-west of England (79.9%), while the largest estimated increase in workforce jobs was in the south-east of England (59,000).

In December, London (91.5%) had the highest estimated proportion of people working in the services sector, while the East Midlands had the biggest proportion of production jobs (14.5%).

The ONS figures also reveal a record number of 1.67 million people working for the NHS in December - 32,000 more than a year earlier.

What has happened to unemployment?

The unemployment rates for both men and women aged 16 years and above have been generally falling since late 2013.

Men's unemployment then stood at 7.4% and women's at 6.9%.

The new total unemployment rate of 3.9% has not been lower since the November 1974 to January 2015 period.

The 4% figure for men is at its lowest since April to June 1975, while the 3.8% for women is the lowest since comparable records began in 1971.

Meanwhile, the number of economically inactive people fell by 117,000 to 8.55 million, a rate of 20.7%, the lowest on record.

The number of job vacancies in the economy increased by 4,000 to 854,000.

Why are jobs, but not investment, flourishing?

By Andy Verity, BBC economics correspondent

If you were being uncharitable to politicians, you might say today's jobs figures demonstrate how little they matter. "Crisis, what crisis?" said recruiters as they hired 220,000 people in the three months to the end of January.

How can you reconcile all that job creation with talk of a Brexit-induced slowdown?

One answer is that the jobs market lags behind the rest of the economy.

Recruiting people takes time; it can be months between noticing you need some new staff and their starting work, so the recruitment decisions reflect recruiters' sentiments months ago.

Another reason may be that our jobs market is highly flexible, which is to say the risks fall on employees.

In uncertain times, a company whose order book is expanding may prefer to take on people who can be "let go" later if things go wrong.

That can be less costly than investing large sums in new plant and machinery, for example - investment which might prove wasted if demand for your goods shudders to a halt in a few months' time.

If that story is right, it helps explain why the economy is generating jobs, but not much investment.

And although there are more of us working, notably women and older people joining the workforce, the amount we each produce is barely growing. That puts a question mark over the sustainability of real wage growth of 1.4% - the strongest in more than two years.

Are companies ignoring Brexit uncertainty and continuing to hire?

It appears that Brexit is not stopping firms hiring staff - at least, not yet.

Tej Parikh, senior economist at the Institute of Directors, said: "Businesses have been steadfast in bringing on board new staff and in creating vacancies, despite question marks over the future path of the economy.

"But with uncertainty around Brexit reaching a crescendo, firms are becoming more and more cagey over their hiring decisions."

Andrew Wishart, UK economist with Capital Economics, said: "There was no sign in the labour market data of Brexit concerns at the start of the year, as the data beat expectations in every regard."

Stephen Clarke, senior economic analyst at the Resolution Foundation think tank, said that Britain was closing in on Nordic employment rates and added: "While business investment has stagnated, firms are choosing instead to invest heavily in new staff."

Wages are still ahead of inflation, despite a lower increase than last month.

What does this all mean for interest rates?

Analysts think that the outcome of Brexit could lead to an interest rates rise later this year.

Mr Wishart said: "If there is a long delay to Brexit or a deal is struck, we suspect the [Bank of England's] Monetary Policy Committee will raise interest rates this summer."

And Mr Parikh added: "Employers will want to avoid a disorderly withdrawal from the EU and will above all be urging policymakers to return some much-needed oxygen to the skills and productivity agenda."

- Published11 March 2019