Boeing announces fixes for its 737 Max aircraft

- Published

Debris from Ethiopian Airlines flight 302

Boeing has issued changes to controversial control systems linked to two fatal crashes of its 737 Max planes in the past five months.

But it is still not certain when the planes, which were grounded worldwide this month, will be allowed to fly.

Investigators have not yet determined the cause of the accidents.

As part of the upgrade, Boeing will install an extra warning system on all 737 Max aircraft, which was previously an optional safety feature.

Neither of the planes, operated by Lion Air in Indonesia and Ethiopian Airlines, that were involved in the fatal crashes carried the alert systems, which are designed to warn pilots when sensors produce contradictory readings.

Boeing said that airlines would no longer be charged extra for that safety system to be installed.

Upgrade

The planemaker has also issued an upgrade to the software that has been linked to the crashes.

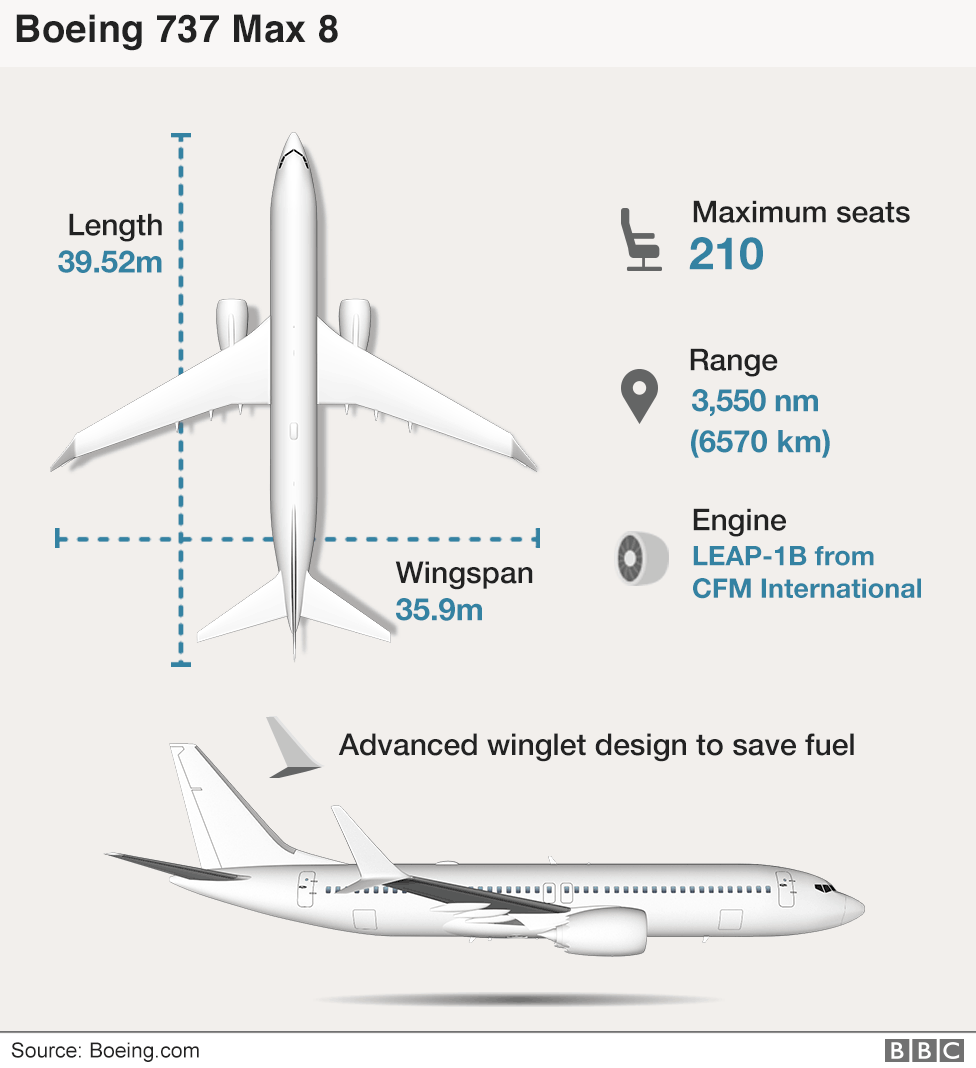

The Manoeuvring Characteristics Augmentation System, better known as MCAS, is software designed to help prevent the 737 Max 8 from stalling.

It reacts when sensors in the nose of the aircraft show the jet is climbing at too steep an angle, which can cause a plane to stall.

But an investigation of the Lion Air flight last year suggested the system malfunctioned, and forced the plane's nose down more than 20 times before it crashed into the sea killing all 189 passengers and crew.

The US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) says there are similarities between that crash and the Ethiopian accident on 10 March.

Boeing has redesigned the software so that it will disable MCAS if it receives conflicting data from its sensors.

Ethiopian Airlines crash: Six charts on what we know

In a briefing to reporters, Boeing said that the upgrades were not an admission that the system had caused the crashes.

Oversight

The FAA itself also came under scrutiny on Wednesday.

At a Senate hearing to discuss airline safety, senators questioned the FAA's acting head, Daniel Elwell, about the regulator's practice that involves employees of a plane manufacturer in the process of inspecting, testing and certifying the company's own aircraft.

The practice was described by one senator, Richard Blumenthal, as leaving "the fox guarding the henhouse".

Mr Elwell denied that it was "self-certification" arguing that the FAA "retains strict oversight authority" of the process. He said that the practice was used "globally", including by the European Aviation Safety Agency.

Mr Elwell added that if the FAA were unable to delegate these tasks to planemakers, it would have to recruit 10,000 more employees, costing the regulator an additional $1.8bn.

Mourners attend a mass funeral for victims of the crashed Ethiopian Airlines flight

The FAA was also criticised for being the last safety regulator to ground the Boeing aircraft following the Ethiopian Airline crash on 10 March.

Calvin Scovel, inspector general of the Department of Transportation, who also appeared before Congress, said: "Other safety regulators around the world decided in their role as safety regulators, they needed to drive risk to zero and they did that by grounding the aircraft."

However, Mr Elwell said the FAA wanted to wait until they received relevant information before they made a decision.

"We may have been the last country to ground the aircraft, but the United States and Canada were the first countries to ground the aircraft with data for cause and purpose," he said.

Mr Elwell said that he was "confident" in the MCAS system and that pilots were trained in how to deal with a situation where a plane drops suddenly.

However, when asked about how he would have handled a plane that dropped 21 times in a matter minutes as the Lion Air flight in Indonesia did before it crashed last October, Mr Elwell, a trained pilot, said: "I'd have to get back to you on the specific."

Timetable

Earlier, announcing the package of cockpit upgrades, Boeing said a final version of the software would be submitted to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) by the end of the week.

But it added that airlines would have to install the new software, give feedback on its performance, and train pilots before the changes could be certified and the planes passed safe to fly again.

There is no timetable for the Boeing 737 Max plane to return to operations

A joint investigation by the US National Transportation Safety Board, France's aviation investigative authority BEA and Ethiopia's Transport Ministry is expected to release a preliminary report into the Ethiopian crash this week.

A Boeing official said: "Following the first incident in Indonesia we followed the results of the independent authorities looking at the data, and, as we are always looking to ways to improve, where we find ways to improve, we make those changes to make those improvements."

- Published14 March 2019

- Published14 March 2019

- Published15 March 2019