Life after a devastating mining disaster

- Published

"My café was my dream. I don't know what will happen to it now," says Geruza França

It was a slow, rainy Saturday summer evening and tourists were beginning to fill up restaurants and cafés in Macacos, a beautiful district in the valleys of Minas Gerais State.

Suddenly the evening calm was broken by the spine-chilling announcement from warning sirens.

"Attention, this is a real emergency. A dam has just broken, evacuate immediately from your homes, follow the exit route to a safe place and wait for further instructions."

The whole place went into panic mode as tourists and residents got into their cars and clogged the town's narrow streets. Some left all of their belongings behind.

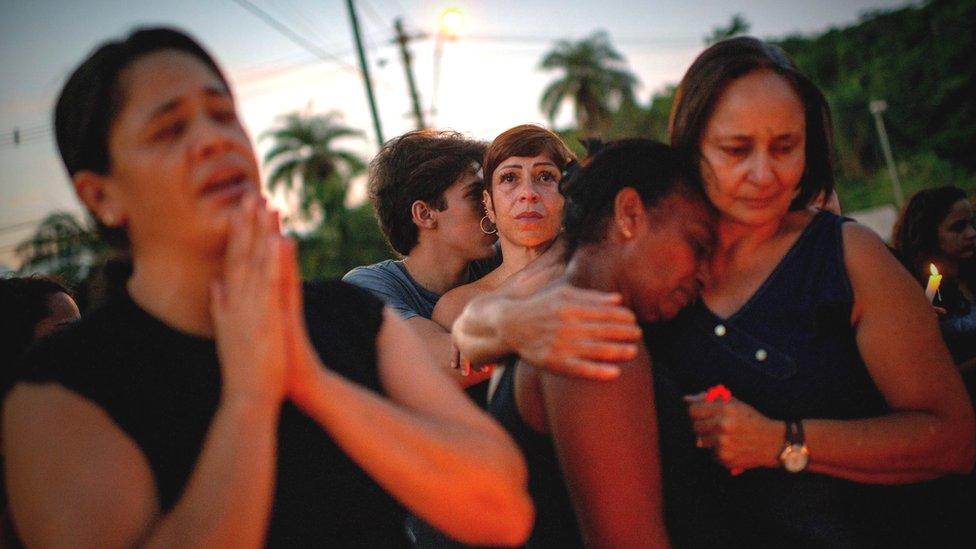

Just two weeks earlier, in neighbouring Brumadinho, an earth embankment tailings dam operated by Brazilian mining giant Vale had broken, killing 308 people. It was the worst industrial disaster in Brazil's history.

Tributes to victims of the Brumadinho dam collapse at an iron-ore mine in Minas Gerais state

Everyone in Macacos thought the same thing was about to happen.

False alarm

But it was a false alarm. Vale had detected a problem in the dams and decided to sound the alert, but the dams hadn't actually been breached.

Fortunately no lives were lost, but Macacos has still been affected. This had been a paradise-like district for wealthy tourists, with high-end restaurants and elegant hotels.

It used to be fully booked all year, but now that everybody is more aware of the tailings dams in the area, nobody wants to come here. Hotel reservations have been cancelled and its most prestigious restaurant has shut down.

I visited Macacos just after Carnival week, which is usually the busiest time of the year. Most residents in lower-lying areas have had to abandon their homes. Among the few still left are business owners. But they don't know whether to wait for things to change or restart their lives and businesses elsewhere.

Tourists have stopped coming to Macacos since the Brumadinho disaster

"Our economy is over, business owners will not be able to make a living any more. All the peace and quiet we had of waking up in a safe place, is gone," Geruza França, who owns Café Judith, tells me.

All her savings from years of working in Europe were put into her café and properties around Macacos.

"My café was my dream. I don't know what will happen to it now. I keep thinking: did I lose my entire dream overnight? It's like someone came and snatched it all away."

Leonardo Batista, who runs the Pousada Kumaru hostel, argues that most of the district is on higher ground and would not be affected by any dam break, but he doesn't know whether businesses will be able to convince the tourists to come back.

Safety 'revolution'

Macacos is one of dozens of districts and towns in Brazil's Minas Gerais state that are feeling the effects of the Brumadinho tragedy.

"Now what Vale?" asks this sign in Macacos

In the aftermath of the disaster, mining practices are finally being overhauled.

Vale and other firms, alongside local authorities, are working to eliminate the risks of further tragedies by decommissioning 50 tailings dams - draining the water from them.

After years of inaction, things are now moving. I recently visited five such dams in Minas Gerais and saw work being done in all but one.

But there are economic consequences as well. The work will take three years to finish and mining activity is being severely disrupted, with Vale having to halt production in some mines.

Having unsafe mining would be catastrophic; having no mining at all is economically devastating.

"We don't want Vale to stop mining here but we don't want to be the ones to pay for their problems," says mayor of Itabirito, Alex Salvador.

In his town, 65% of its revenues come from Vale operations that have now stopped due to court orders. He is already having to plan cuts in education, health and public cleaning.

Alex Salvador: "We don't want Vale to stop mining here but we don't want to pay for their problems."

On top of that there are safety concerns. Should the two dams near Itabirito break, the town would be hit within a few hours. Just a few days after Brumadinho, the town's authorities came up with an evacuation plan.

Itabirito now has signs pointing to escape routes and meeting points on high ground. Warning sirens will be installed next month.

Global consequences

The problems of Minas Gerais and Vale are not just affecting local economies. Global iron ore prices have soared since January, as Vale is the world's number one producer - and Minas Gerais state accounts for 45% of its iron ore output.

Iron ore was trading at $74 a tonne before Brumadinho. It reached $95 a tonne immediately afterwards and is now about $85 a tonne.

Analysts say prices will remain high for some months, as many questions remain. How much will Vale have to pay in compensation and fines? Will new mining regulations increase production costs?

In a few months, these disruptions will start pushing up the costs of steel and construction worldwide.

Yet because Vale is such a powerful player in global commodities, it is actually benefiting financially from this supply disruption.

Immediately after the disaster it saw some $19bn wiped off its share value. But as no other firm has the capability to take over Vale's market share, the iron ore price rise is now working to its advantage.

Mud from the Vale dam collapse - iron ore prices have soared since the disaster

Even with drastic production cuts, Vale shares are now at the same level as they were shortly before the tragedy, increasing the anger felt by communities claiming reparation from the firm.

Stricter control

One thing is virtually unanimous amongst iron ore experts: Brazil needs stricter control of its mining practices, and decommissioning the tailings dams is a matter of urgency.

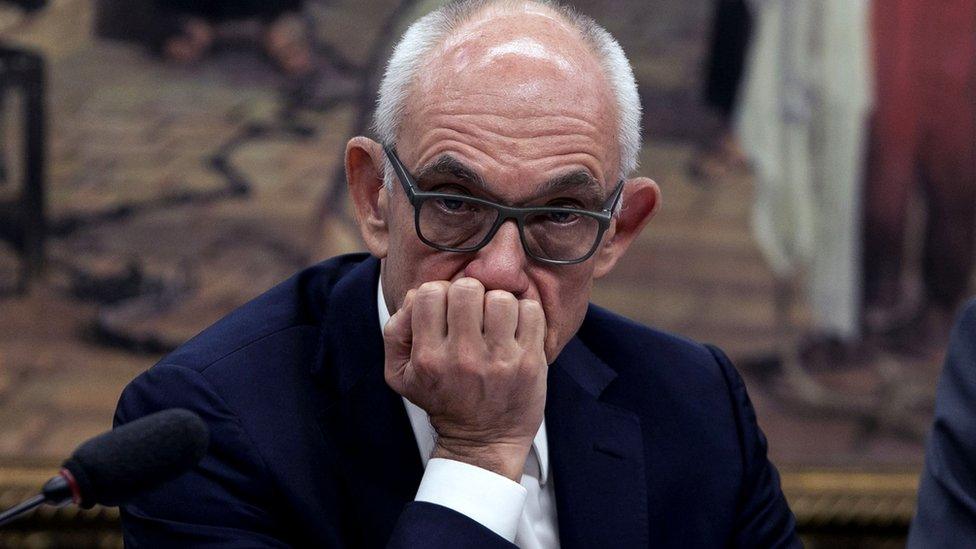

Brazilian authorities are still investigating the causes of the Brumadinho tragedy. Some Vale executives have been arrested and questioned, but no one has yet been charged.

Earlier this month Vale's chief executive Fabio Schvartsman stepped down after a disastrous appearance in Congress where he told MPs that "Vale is a Brazilian jewel" and "should not be condemned" for what he described as "an accident".

Vale's Fabio Schvartsman was forced to step down after a disastrous press conference

Vale executives declined a BBC request for an interview. In a statement the company said it is "100% focused on supporting those affected and responding to the dam break".

Apart from decommissioning mines, Vale has made donations to those affected and organising relocation for those in areas at risk.

Back in Macacos, where local business owners are desperately looking for answers from Vale, there is still much anger and little faith in the company.

Geruza França is now thinking about closing down her café. What she can't understand is how such a powerful company caused so much destruction in so many people's lives.

"How can these executives behave like this? I don't think they are made of flesh and blood. I think they are made of iron ore."

- Published3 March 2019

- Published15 February 2019

- Published1 February 2019

- Published30 January 2019

- Published30 January 2019

- Published28 January 2019

- Published26 January 2019