Boeing admits it 'fell short' on safety alert for 737

- Published

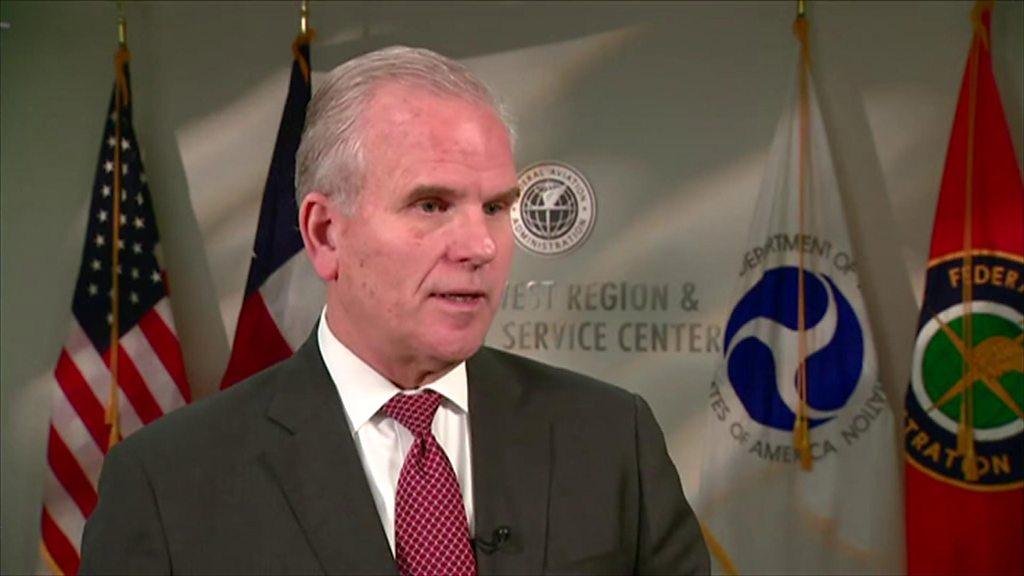

Boeing boss Dennis Muilenburg speaking in May: 'We're confident on the plane's safety'

Boeing has admitted it "fell short" when it failed to implement a safety alert system on the 737 Max.

The aircraft was grounded globally in March after two crashes within months.

Boeing boss Dennis Muilenburg said a mistake had been made in the software for a cockpit warning light called an "angle-of-attack (AOA) disagree alert".

He said: "We clearly fell short and the implementation of this angle-of-attack disagree alert was a mistake, right, we did not implement it properly."

In an interview with Norah O'Donnell of CBS News he said Boeing was now fixing the problem.

The alert could have notified pilots and maintenance crews that there was a problem early in the flight.

One flight safety expert said if there had been an AOA disagree alert on board the Ethiopian airlines flight it "would have been the very first clue" for the pilots that something was wrong.

Chris Brady, a pilot and author of The Boeing 737 Technical Guide said: "I'm fairly confident that the Ethiopian Airlines flight probably would not have crashed if they had had the AOA disagree alert" on the aircraft.

The Ethiopian Airlines crash killed all 157 on board

Erroneous reading

Ethiopian Airlines flight ET 302 crashed after an erroneous reading from one of the AOA sensors triggered a flight control system (MCAS) which repeatedly pushed the nose of the aircraft down.

All 157 people on board were killed.

Mr Brady believes that if there had been an alert warning light showing that the AOA sensors were giving different readings, then the pilots might have followed an emergency procedure at an earlier point in the doomed flight.

The procedure, detailed by Boeing in a bulletin to airlines and pilots in November subsequent to the Lion Air crash off Indonesia, involves flipping two switches, and turns off an automatic control system for the plane's stabilisers.

Boeing said in a statement a month ago that the "alert has not been considered a safety feature on airplanes and is not necessary for the safe operation of the airplane".

Analysis by Tom Burridge, BBC Transport Correspondent

This is perhaps the clearest admission so far from Boeing that at least one aspect of the aircraft's build wasn't done properly.

We can't say for certain that an angle of attack disagree alert, which was missing, would have made a big difference.

However, it could have provided the pilots with a useful clue, possibly within seconds of take-off, that something was not right.

Ask any pilot if they would have wanted the alert in their cockpit and you'll get a resounding "yes".

The alert is about flagging that the readings from the plane's two angle of attack sensors don't match.

And the fact that an erroneous reading from one of those sensors kick-started a flight control system, which pushed the plane's nose repeatedly down before it crashed, means the missing alert will surely be of interest to investigators and lawyers representing relatives of those who were killed.

Mr Muilenburg also admitted in the CBS interview that the company knew that the alert system was not active on all 737 Max jets in 2017 and yet did not tell the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) for 13 months.

He said: "Our communication on that was not what it should have been."

And he issued another apology, saying "it feels personal".

He said that the crashes have had "the biggest impact on me" of anything in his 34 years at the planemaker.

Return to service

The head of the airline industry's trade body, IATA has said the 737 Max is unlikely to re-enter service before August.

Director General Alexandre de Juniac said "we do not expect something before 10 or 12 weeks", although he added a final decision was up to regulators.

Mr de Juniac told reporters in Seoul on Wednesday that IATA was organising a summit with airlines, regulators and Boeing in five to seven weeks to discuss what is needed for the 737 Max to return to service, he said.

Boeing's 737 Max aircraft was grounded in March

He hoped that regulators could "align their timeframe" on when the aircraft would be back in the skies.

US operators United Airlines, Southwest Airlines, and American Airlines have removed the 737 Max from their flight schedules until early to mid-August.

Earlier in the day, Mr Muilenburg had told shareholders Boeing aimed to ramp up its long-term production rate of the 737 Max to 57 a month after cutting monthly output to 42 planes in response to the groundings.

- Published29 May 2019

- Published23 May 2019

- Published23 May 2019