What's wrong with buying a dinosaur?

- Published

Tyrannosaurus rex is the rock star of the dinosaur world; specimens fetch more than older fossils

Fossils are in fashion, with private buyers snapping up prehistoric remains online and at auction but the trend is raising concerns within the scientific community.

In the saleroom at Christie's auction house in London, buyers are crowding round to view - not works of fine art, antique furniture or jewellery - but fossils from an era so far in the past it is hard to fathom.

There are Triceratops horns, the teeth of a Tyrannosaurus rex, and the tail of a duck-billed dinosaur from 66 million years ago.

Bidders from as far apart as California and Hungary join the auction online and the murmurs of excitement rise as the room is shown slides of such palaeontological treasures as oil-black teeth from a Megalodon - a giant prehistoric shark - or Sauropod eggs and fossilised dragonflies.

Private buyers have been showing a growing interest in ancient remains over the past few years. Bidders from more than 50 countries regularly participate in sales like these, says James Hyslop, head of science and natural history at Christie's.

Mosasaur skulls are popular with private buyers

Celebrity interest - Leonardo DiCaprio, Russell Crowe and Nicolas Cage are all known to have bought prehistoric treasures - has helped make them fashionable.

Such fossils may not yet compete with fine art in terms of the most expensive sale tags, but the boom in interest means that prices are rising.

Elephant bird eggs sold for £20,000-30,000 a decade ago, for example - now they're selling for £100,000.

Mr Hyslop points out one of the sale's rarest specimens: a female ichthyosaur fossil. At 3.5m (11ft) this is the largest ever sold at auction. This prehistoric fish-lizard swam the oceans of the early Jurassic, 184 million years ago.

Christie's recently sold this rare pregnant ichthyosaur fossil

On close inspection there are also the rare remains of two embryos in its rib cage: it was pregnant. Bids for it reach £240,000.

Mr Hyslop puts the growing interest in prehistoric remains down to a generation that grew up on the first batch of Jurassic Park films (1993-2001).

"We love this subject," he says. "People just love what it stands for". What it stands for is a combination of popular science and popular history, but also the excitement of breaking new ground. According to National Geographic, 50 new species of dinosaur are being discovered every year.

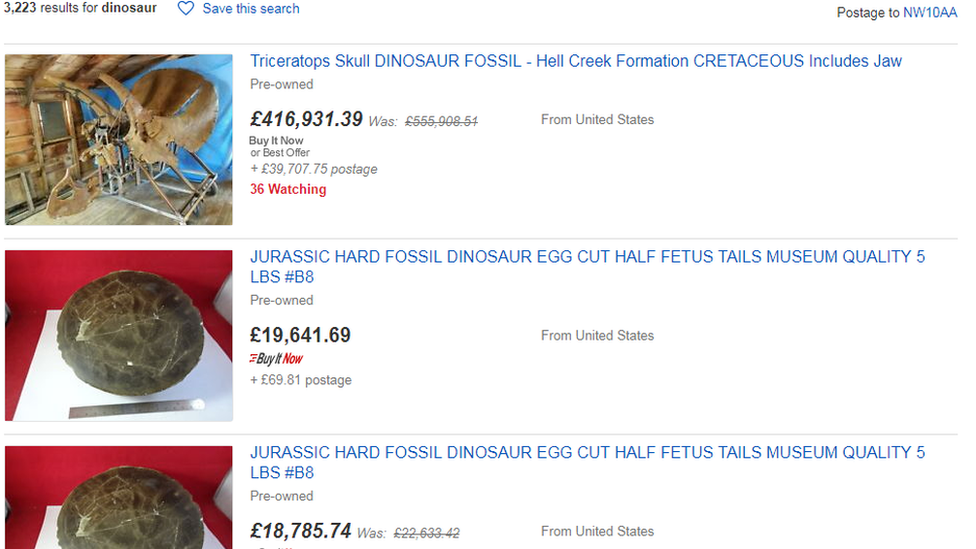

On the online trading site eBay, Mosasaur fossils are popular. The remains of these striking marine reptiles are now changing hands at a rate of around 100 every month in the UK - a 42% increase on the year before.

Searching eBay turns up hundreds of specimens for sale

But you can also find Triceratops skulls and baby Allosaurus skeletons, ranging in price from a few thousand pounds to hundreds of thousands - eBay reported a 22% increase in fossil sales last year.

However this rising popularity is concerning scientists: for one thing it is fuelling the illicit trade in fossils.

While some countries like the US, will allow private fossil hunters to sell-on their finds on a "finders keepers" basis, many others including China, Mongolia and Brazil ban the export of all specimens. They're also working to reclaim illegally excavated specimens.

US Immigration and Customs Enforcement has seized $44m worth of dinosaur fossils over the last five years

The 70 million-year-old skull of a Tyrannosaurus bataar, an Asian relative to Tyrannosaurus rex, that actor Nicolas Cage bought at auction in the US in 2012, was later reclaimed by the Mongolian government, for example.

Yet the palaeontologist who won that legal battle, Bolortsetseg Minjin, says despite the Mongolian government's determination to stem the flow there are still plenty of new cases of poaching, which she says risk causing irrevocable damage to the specimens.

"Poachers don't have skills and only go for the parts that'll make them money, like destroying whole skeletons just for teeth," she says. "It's treating them like a commodity but these fossils are priceless."

Private buyers might not realise it, she says, but unless they are sure of a fossil's provenance, buying it could indirectly be causing harm by fuelling that black market trade.

Bolortsetseg Minjin has fought to repatriate more than 30 fossils originally excavated in Mongolia

The booming private market can have a knock-on negative effect even when legal, says Dr Susannah Maidment from the Earth Sciences department of London's Natural History Museum.

"The problem is these specimens go on sale for huge amounts of money, far more than museums can afford.

"Our acquisition budget for specimens across the entire museum, not just palaeontology, amounts to tens of thousands of pounds annually. But many of these big dinosaur specimens will sell for well over a million dollars," she explains.

When specimens are privately owned that can act as a barrier to scientific research, she argues.

Dr Maidment studying a Stegosaurus specimen at the Prehistoric Museum in Price, Utah

One of the London Natural History Museum's prize exhibits is Sophie, a 151 million-year-old complete Stegosaurus skeleton. Before the museum acquired it, no-one actually knew how many bones there were in the backbone of a Stegosaurus or how many plates it had along its spine, says Dr Maidment.

The museum, like many other scientific institutions, won't research or publish work on privately-owned specimens as a matter of principle, because scientific rigour relies on replicating research. A private owner may allow one researcher to examine their fossil but then might refuse access to others.

Global Trade

On the other hand, the process of exploration and excavation is labour intensive and expensive.

"It's a conflict because we don't have the resources to collect these ourselves, and we wouldn't know about them if commercial dealers weren't digging them up," Dr Maidment says.

Yet when the purpose of the excavation is private profit there's the risk that gathering essential contextual data will be neglected, she adds.

Sophie the Stegosaurus is one of the London Natural History Museum's prize exhibits

Mr Hyslop argues we shouldn't demonise private buyers as if they were "a Bond villain who's sitting on his dinosaur bones and never letting anyone else look at them". Many private buyers are happy for their items to be displayed and studied, he points out.

But often the problem is on a much simpler level, says Dr Matthew Carrano, curator of Dinosauria at The Smithsonian in Washington - that new discoveries may just be missed altogether.

With the rate of dinosaur discoveries showing no sign of slowing, he says a private find may slip under the radar as "there's no catalogue or account of them aside from the occasional high-profile example that might make the news.

"The rest are sold and bought without any publicity and just disappear into private hands, often without science knowing they exist."