Stockpicking: What goes up may go down

- Published

Everybody loves Warren: At the Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting

If what goes up, must come down, it stands to reason that a professional stockpicker can't get it right all the time.

Sooner or later, the fairy dust evaporates, as Neil Woodford found out this week when he was forced to suspend his flagship fund.

A stockpicker, or fund manager, analyses the potential of different shares to see if they will make a good investment.

Investors, like big institutions such as pension funds, put money into funds run by these stockpickers, hoping the savings will grow.

What makes Mr Woodford's travails so startling is that he was one of a very small group of fund managers able to attract investors on the strength of his name alone.

Powered by glittering success in the past, Mr Woodford's troubles show that even these Pied Piper-like figures have their bad years.

"No one would expect a fund manager to keep beating the index or their rivals every year," said Russ Mould, investment director at AJ Bell. "Each has a different style and angle which might not work in some years."

As the following fund managers show, no-one is infallible, but they can also recover.

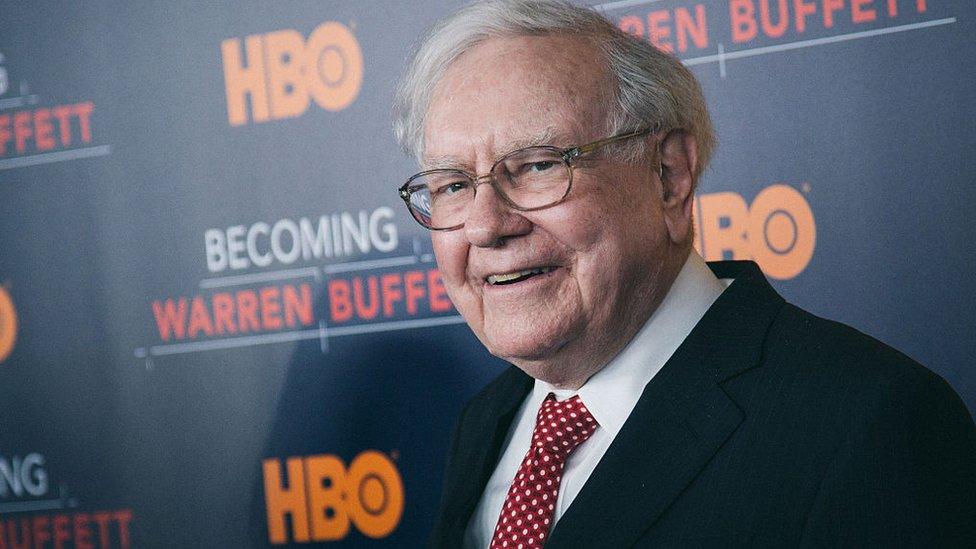

Warren Buffett

When it comes to stockpickers, none is bigger than the big cheese himself, Warren Buffett.

He is chairman and chief executive of Berkshire Hathaway, but devotees call him the Oracle (sometimes Sage) of Omaha, a reference to the Nebraska city where the company is based.

Warren Buffett is known as the Sage of Omaha

His somewhat folksy and outwardly simple approach to investing - buy low, buy what you understand, and hold - has helped him to amass 1.5 million Twitter followers.

That's not exactly Kim Kardashian West territory, but it's not bad for a bridge-playing, 88-year-old who lives in the same house he bought in 1958.

He's worth close to £85bn.

A measure of Mr Buffett's popularity is Berkshire Hathaway's annual meeting, an event that attracts tens of thousands of investors to Omaha, with millions more watching online.

This event - which has been dubbed the Woodstock for capitalists - is where investors get insights and strategy from Mr Buffett and his long-time partner Charlie Munger,

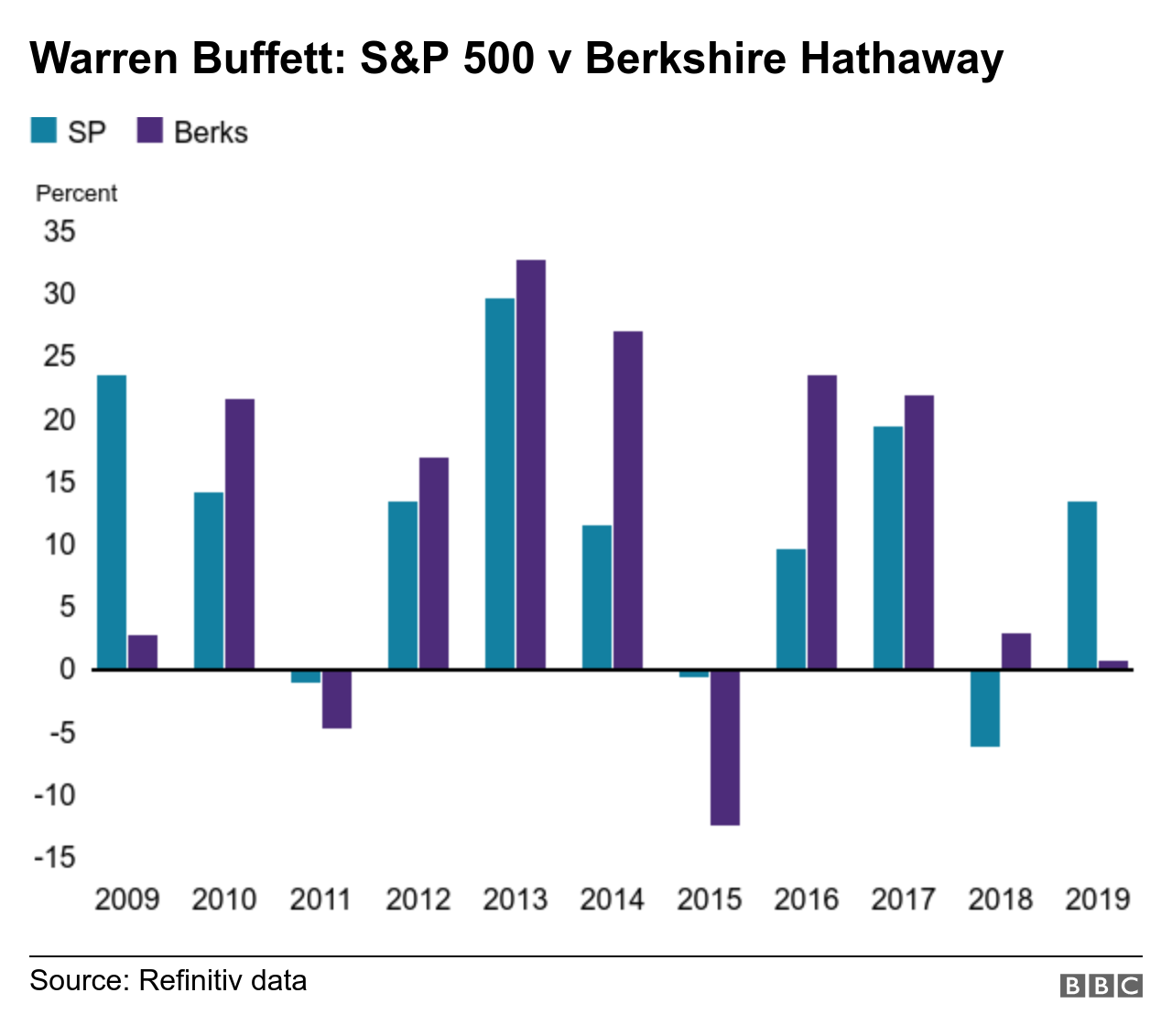

If you'd invested $100 in Berkshire Hathaway in 1965, the year Mr Buffett took over, it would be worth well over $2m now. But such returns shouldn't mask some mistakes, many in recent years.

Berkshire's 2013 purchase of Heinz, and subsequent merger with Kraft, lost billions. And Mr Buffett described his investment in Tesco as a big mistake. "An attentive investor... would have sold Tesco shares earlier," he said.

Berkshire Hathaway is a big investor in Wells Fargo, a bank that has been beset by scandal. And Mr Buffett came late to the tech share boom, saying he didn't fully understand the market. But he started buying Apple stock in 2016, and more recently began investing in Amazon.

Mr Buffett has always been honest about his failures, another reason the general punter admires him.

Anthony Bolton

For many years, when Mr Woodford was mentioned in a sentence, it would very often be alongside Anthony Bolton - a fund manager of "rock star" status with a penchant for composing classical music.

Mr Bolton achieved near legendary status for delivering average annual returns of nearly 20% over the 28 years he managed Fidelity's Special Situations fund.

An investment of £1,000 in 1979 would have grown into £143,200 by the time Mr Bolton handed over control of the Special Situations fund in 2007.

Anthony Bolton was known as the "quiet assassin"

During his time in the City, the 69 year-old was known as the "quiet assassin" - a nickname he loathed - for preventing Carlton Communications boss Michael Green from becoming chairman of a newly-merged ITV.

A self-confessed "contrarian", Mr Bolton avoided the ill-fated dot.com boom while others piled in.

Going against the crowd was part of Mr Bolton's investing style, which also included avoiding complicated businesses - a particular philosophy that made his next career move all the more baffling.

Anthony Bolton mixed stockpicking with composing classical music and released his own CD

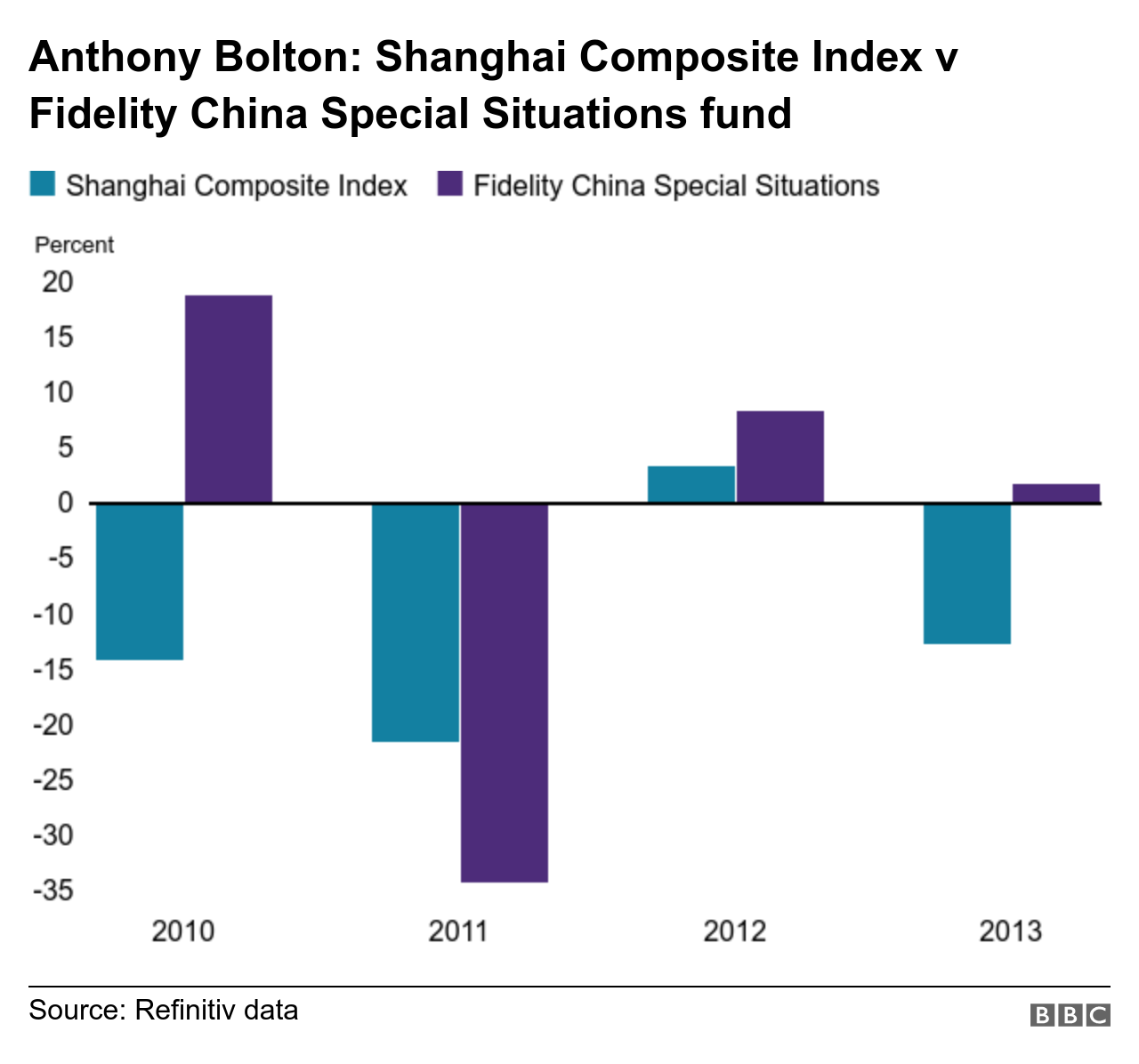

In 2010, Mr Bolton emerged from semi-retirement and swapped Sussex for Hong Kong to launch the Fidelity China Special Situations fund, based on the idea that the country would become less export-led and its economy would be fuelled by an emerging middle class.

His star power attracted 80,000 small investors and millions of pounds to the fund, but it became clear early on that even the mighty Mr Bolton could be wrong-footed.

After three years, a person who had invested £1,000 and reinvested their dividends was left holding £945.

Mr Bolton admitted in 2014 - the year he really did retire - that he had got it wrong in China, that he had expected the stock market to rise when in fact it went the other way.

Though still remembered as a City titan, Mr Bolton's Chinese adventure left his star a little tarnished.

Terry Smith

Terry Smith once said: "I don't start fights with people but I will finish them."

The East End-born fund manager, 66, who now lives in Mauritius, is known for his combative style.

Terry Smith is known for his combative style

When he launched his Fundsmith Equity Fund in 2010, he did so with the aim of shaking-up the "fat and bloated" UK fund management industry.

There are no sacred cows for Mr Smith.

As a research analyst at investment bank BZW in the 1980s, he recommended that client sell shares in Barclays - which also happened to own BZW.

The image of a bruiser, however, is at odds with his patient and meticulous approach to investing which is "buy good companies, do not overpay, and do nothing".

The former boss of broker Collins Stewart and Tullett Prebon, invests his main equity fund in around 25 high quality firms such as Microsoft and Nestle.

The Fundsmith Equity Fund has £17bn of investors money and even though it returned 2.2% in 2018, its weakest since it was set up, it still beat the MSCI World benchmark, which was down 3%.

However, Mr Smith very recently stepped back from the day-to-day management of the Fundsmith Emerging Equities Investment Trust which, although in positive territory, has failed to outperform wider emerging market stocks since its launch in 2014.

It's a little bit of a bloody nose for Mr Smith, but he can take it.

Jack Bogle

Jack Bogle, who died this year aged 89, is hailed as the inventor of the index mutual fund - pooling resources to invest in a wide spread of shares. It opened investment to people with limited resources.

"Jack did more for American investors as a whole than any individual I've known," Mr Buffett said earlier this year.

In his heyday: Jack Bogle in 1995

His Vanguard group of investment firms now has more than $5 trillion under management, built on his belief that "wise investors won't try to outsmart the market". Instead, they'll buy cheap funds and diversify.

The fact that so many highly-paid money managers failed to predict the crash only strengthened his belief that mom and pop investors should beware the experts.

When Mr Bogle started out, his mutual fund strategy left the finance industry aghast. His rock-bottom fees, and marketing of funds directly to investors rather than through brokers, eroded the earnings of established firms.

But in his later years he became a strong critic of the very industry he established, chiefly for the high charges.

He advocated that young investors, if they needed an adviser at all, opt for online robo-advisers where human intervention was kept to a minimum.

- Published7 June 2019

- Published6 June 2019

- Published5 June 2019