How a ransomware attack cost one firm £45m

- Published

Aluminium maker Norsk Hydro refused to pay ransomware hackers - many others pay up

When malicious hackers disable your business and demand a ransom, should you pay up? Many firms do out of desperation, turning to intermediaries to help broker the deal. But law enforcement says this just makes things worse.

Imagine the excitement when hackers gained a foothold in the computer system of Norsk Hydro, a global aluminium producer.

We don't know when it was, but it's likely that once inside they spent weeks exploring this group's IT systems, probing for more weaknesses.

When they eventually launched their ransomware attack, it was devastating - 22,000 computers were hit across 170 different sites in 40 different countries.

Chief information officer Jo De Vliegher reopens the ransom note that appeared on computers all over the company. It read: "Your files have been encrypted with the strongest military algorithms... without our special decoder it is impossible to restore the data."

Watch: The factory brought to its knees by ransomware hackers

The entire workforce - 35,000 people - had to resort to pen and paper.

Production lines shaping molten metal were switched to manual functions, in some cases long-retired workers came back in to help colleagues run things "the old fashioned way".

In many cases though, production lines simply had to stop.

Imagine the hacker's anticipation as they waited to receive a reply to their ransom note. After all, every minute counts for a modern manufacturing powerhouse. They probably thought they could name their price.

But the reply never came. The hackers were never even asked how much money they wanted. Imagine the shock.

All that work. For nothing.

Technology explained: what is ransomware?

It's been more than three months since Norsk Hydro was attacked and they are still many months away from making a full recovery. It's so far cost them more than £45m.

But what they've lost in productivity and revenue, they've arguably gained in reputation.

The company's response is being described as "the gold standard" by law enforcement organisations and the information security industry. Not only did they refuse to pay the hackers but they've also been completely open and transparent with the outside world about what happened to them.

But there are many other companies and organisations who make the opposite choice, and evidence is growing that ransomware hackers are increasingly being paid off secretly by victims - and their insurance companies - looking for the easy way out.

"It's become a simple business case for many organisations to pay, and at this point it's a known secret that this is happening," says Josh Zelonis, cyber-security analyst at Forrester.

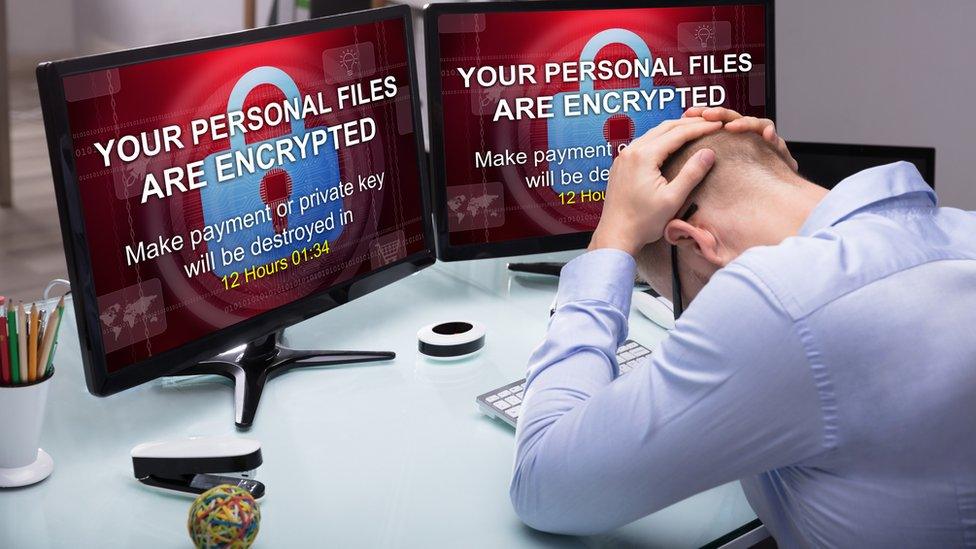

A ransomware attack can cause huge damage to a company's operations

Secrecy surrounds the practice because organisations are concerned about the possibility of litigation and the damage to their reputations following an attack, says Mr Zelonis.

"And a lot of the time incident response companies are being brought in to broker the transaction with the adversaries themselves in order to ensure that the payment is made and recovery is possible," he says.

Sources in the information security industry have described multiple occasions when large, well-known companies have paid out thousands of pounds - in some cases hundreds of thousands - to hackers and not told the public or even shareholders.

Just last week, a Florida town paid hackers $600,000 (£475,000) to get its computers working again after a ransomware attack disabled email, hit emergency response systems and forced staff to use paper-based admin systems.

It's a troubling trend that's prompted Europol, the European Union's law enforcement agency, to re-issue its warning that paying ransoms fuels hackers and often leads to more organised crime.

One US-based company, Coveware, specialises in negotiating ransoms between hackers and their victims. Visiting its offices in Connecticut, it's clear it operates at the sharp end of cyber-crime.

There is no permanent office, instead people move around shared workspaces. The entire team is dispersed around the world.

Coveware's Bill Siegel says ransomware attacks can destroy a company

Chief executive and founder Bill Siegel admits that the service is an "unpalatable" one, but insists that it is needed. He wouldn't give details on the companies that he's helped but says: "At any one time we have half a dozen to a dozen cases, some of the companies are big, including public companies and name brands."

The company's own research indicates that the hackers' demands, usually an exchange of untraceable Bitcoin, are increasing.

"Ideally we wouldn't pay or we'd negotiate down a lot," says Mr Siegel, "but we recognise that when a company needs to pay - and it's a large number - then that's what needs to happen, and that can be seven figures.

"Everybody recognises that this is not a good outcome but you're dealing with the life or death of a company."

The most infamous ransomware virus was called WannaCry and infected 200,000 computers in at least 150 countries, including causing notable disruption to the National Health Service in the UK.

Since then ransomware attack numbers have actually declined significantly.

Cyber Security vendor Trend Micro estimates that numbers could have dropped 91% in the past year. But data from many other vendors points to a rise in more targeted attacks, where companies and organisations, instead of individuals, are in the cross-hairs.

Norsk Hydro's Jo De Vliegher says "it's a very bad idea to pay"

Researchers at cyber-security company Malwarebytes say that compared to the same time last year, business detections of ransomware have risen more than 500%.

Back at Norsk Hydro, Mr De Vliegher said he tries not to think of the hackers and takes no satisfaction in knowing he foiled their plans.

"I think in general it's a very bad idea to pay," he says. "It fuels an industry and it's probably financing other sorts of crime. It goes against our company values and we have good foundations and good people.

"But I understand why, for some companies who are less secure, this can be the only option."

His words are echoed by Europol's head of the European Cybercrime Centre, Steven Wilson.

"Companies need to understand that if you continue to pay a ransom it perpetuates the crime," he says. "It encourages the criminals to commit further crimes.

"If you pay, you're fuelling organised crime on a global basis."

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external