Can hit songs be worth more than gold?

- Published

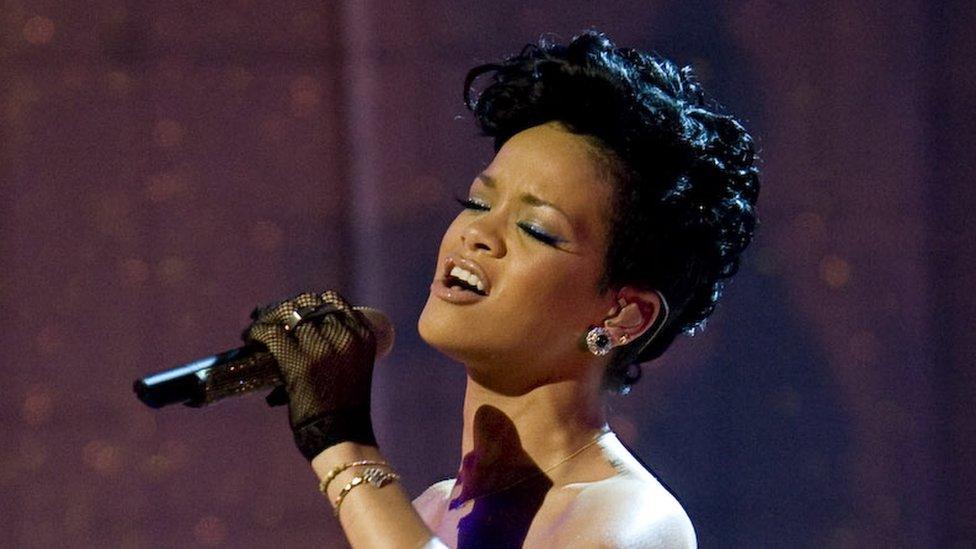

Rihanna's Umbrella could be an investment for a rainy day

Ever wondered who gets paid when you hear a hit record played out loud?

Maybe you've spent money on buying the music or subscribing to a streaming service.

Or perhaps the makers of a TV series or a commercial have paid to use it.

So who benefits from that money? Well, the people who sang and played on the session (or some of them, anyway), plus the songwriters, plus the record company, plus the publishing company.

But these days, it doesn't stop there. Nowadays even songs can have shareholders.

Hipgnosis Songs Fund is steadily building up a catalogue of hit songs and inviting big institutional investors to share in the proceeds.

That means a much wider group of people can see an income from music royalties.

The fund floated on the London Stock Exchange in July 2018 and recently published its first-ever annual results.

The man who founded it, Merck Mercuriadis, says hit songs are "as investible as gold or oil".

What does that mean exactly?

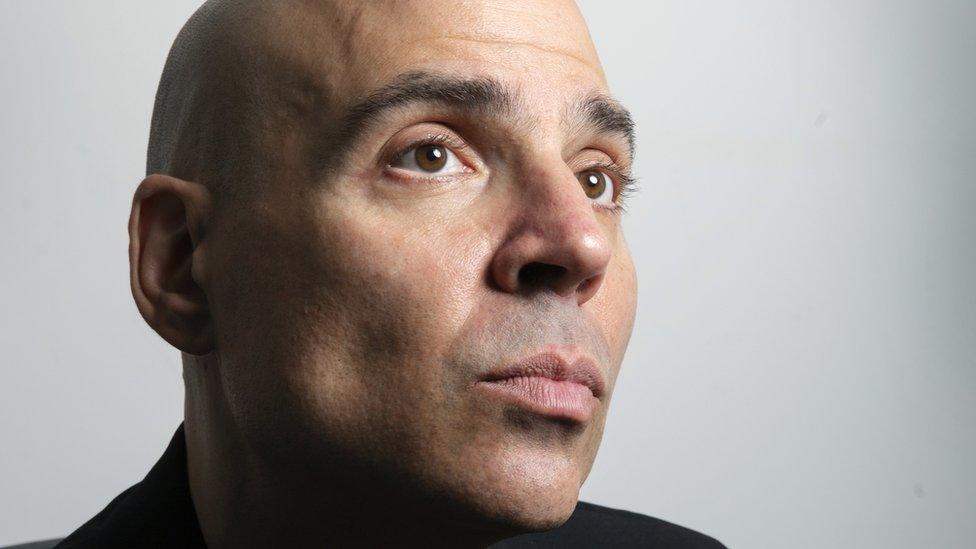

Mr Mercuriadis has a solid pedigree in the music industry, having managed artists including Beyoncé, Elton John, Iron Maiden and Guns N' Roses.

Merck Mercuriadis is a music industry veteran

"I have 35 years' experience in this business, managing some of the greatest artists of all time, and I know what's a good song and what's not," he told the BBC.

However, the songs Hipgnosis buys have to be established earners. "We don't speculate on new songs. The proven hit songs that we buy have predictable and reliable income streams and a track record that goes back many years."

Mr Mercuriadis says songs are "uncorrelated assets". That means their performance is not subject to random events, such as Donald Trump's tweets or Brexit uncertainty.

"When people have a good time, they celebrate to music," he says.

"When times are hard, people use music as their escape. So music is always being consumed."

How did all this start?

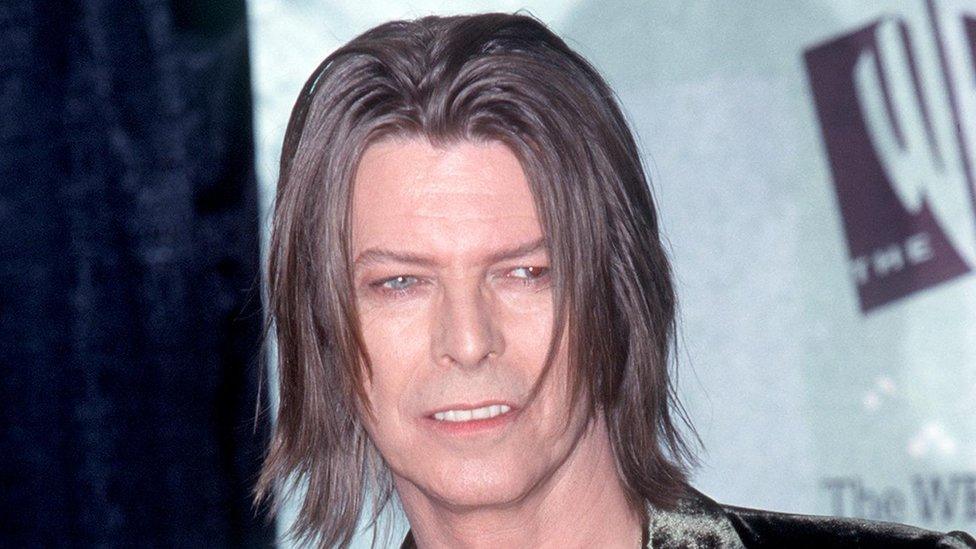

The idea of investing in songs goes back at least as far as 1997, when David Bowie convinced the financial world to buy securities that gave people a share in his royalties for 10 years.

These "Bowie bonds", which were snapped up by US insurance giant Prudential Financial for $55m (£38m), committed Bowie to repay his new creditors out of future income and gave a fixed annual return of 7.9%.

David Bowie was influential in finance as well as in music

But that was down to the Thin White Duke himself peddling his own intellectual property. Hipgnosis, on the other hand, is deliberately buying up the rights to other people's songs, treating them as an asset that can provide a stable income.

Its figures show that by the end of March this year, it had spent £120m on buying up the rights to 3,096 songs.

Since then, it has bought even more and now has a portfolio of 5,891 songs.

Have I heard of any of these songs?

Well, you probably know Rihanna's Umbrella, which spent 10 weeks at number one in the UK in 2007.

Umbrella was co-written by Rihanna with Christopher "Tricky" Stewart, Kuk Harrell and The Dream (real name Terius Youngdell Nash).

Hipgnosis now owns 100% of Tricky Stewart's stake and 75% of The Dream's bit, having done deals with those two songwriters. Put that down to the fragmented nature of modern music copyright.

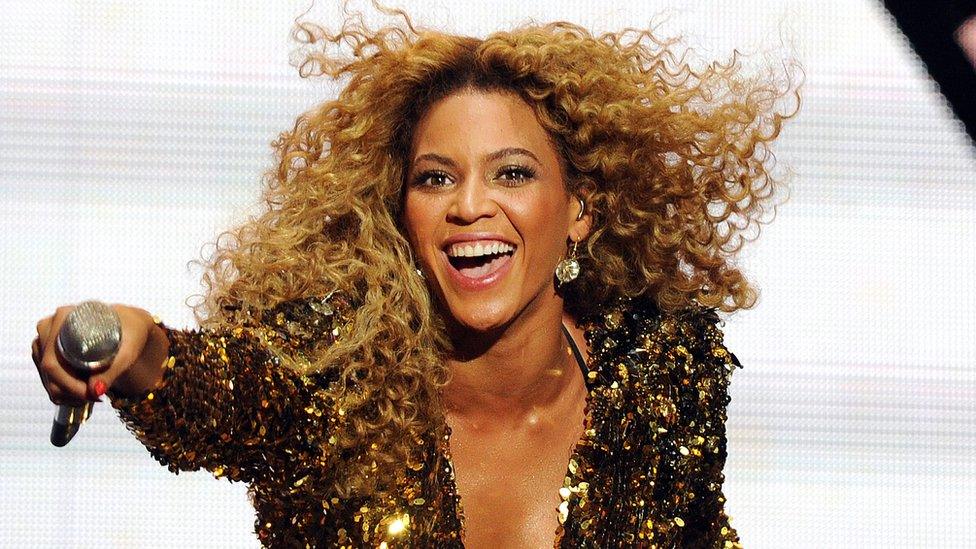

Tricky Stewart and The Dream also teamed up with Beyoncé to write her song Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It), so Hipgnosis owns a chunk of that too.

Perhaps its biggest single acquisition so far came in May, when it bought Eurythmics musician Dave Stewart's 1,068-song catalogue.

The main prize there is Stewart's half of Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This), which he co-wrote with Annie Lennox. That's the UK's most streamed song of 1983, so future revenues seem guaranteed.

Hipgnosis has a stake in Beyoncé's repertoire

Still, Mr Mercuriadis says Hipgnosis doesn't just sit back and wait for the money to roll in.

"We actively manage the songs better than they've been managed previously," he says.

Many large music publishers have as many as 20,000 songs per person they employ, so each song doesn't get that much attention.

In the case of Hipgnosis, there is a team of 15 people working the catalogue, which means about 300 songs per person.

"We treat each song as if it was a business in its own right," he says.

That means maximising the opportunities for that song to generate income, whether in TV commercials and video games or in cover versions by new artists.

Is there a catch?

Well, you can see how the rise of music streaming is central to all this.

In the old days, when CDs ruled the roost, consumers would make a one-off payment to buy an album.

Now, however, a music stream means a continuing revenue stream. Those Spotify, Deezer and Apple Music payments may be small, but they keep on coming.

Mr Mercuriadis points to research by JP Morgan that forecasts huge growth in the number of users of streaming services, from 200 million today to an estimated two billion worldwide by 2030.

"What streaming has done is, it's given the consumer a more convenient way to consume music - and that's something they're willing to pay for," he said.

Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This) is being played on streaming services 36 years after it was released. However, there is of course no guarantee we will still be listening to Umbrella in 2043.

Hipgnosis is taking an informed punt on the future viability of the tunes it acquires. But then, just like chart placings, investments do go down as well as up.

- Published23 June 2019

- Published24 May 2019

- Published4 January 2017

- Published11 January 2016