No-deal Brexit 'could cost farms £850m in profits'

- Published

- comments

Farmer Colin Ferguson says he wants "the Brexit uncertainty to end"

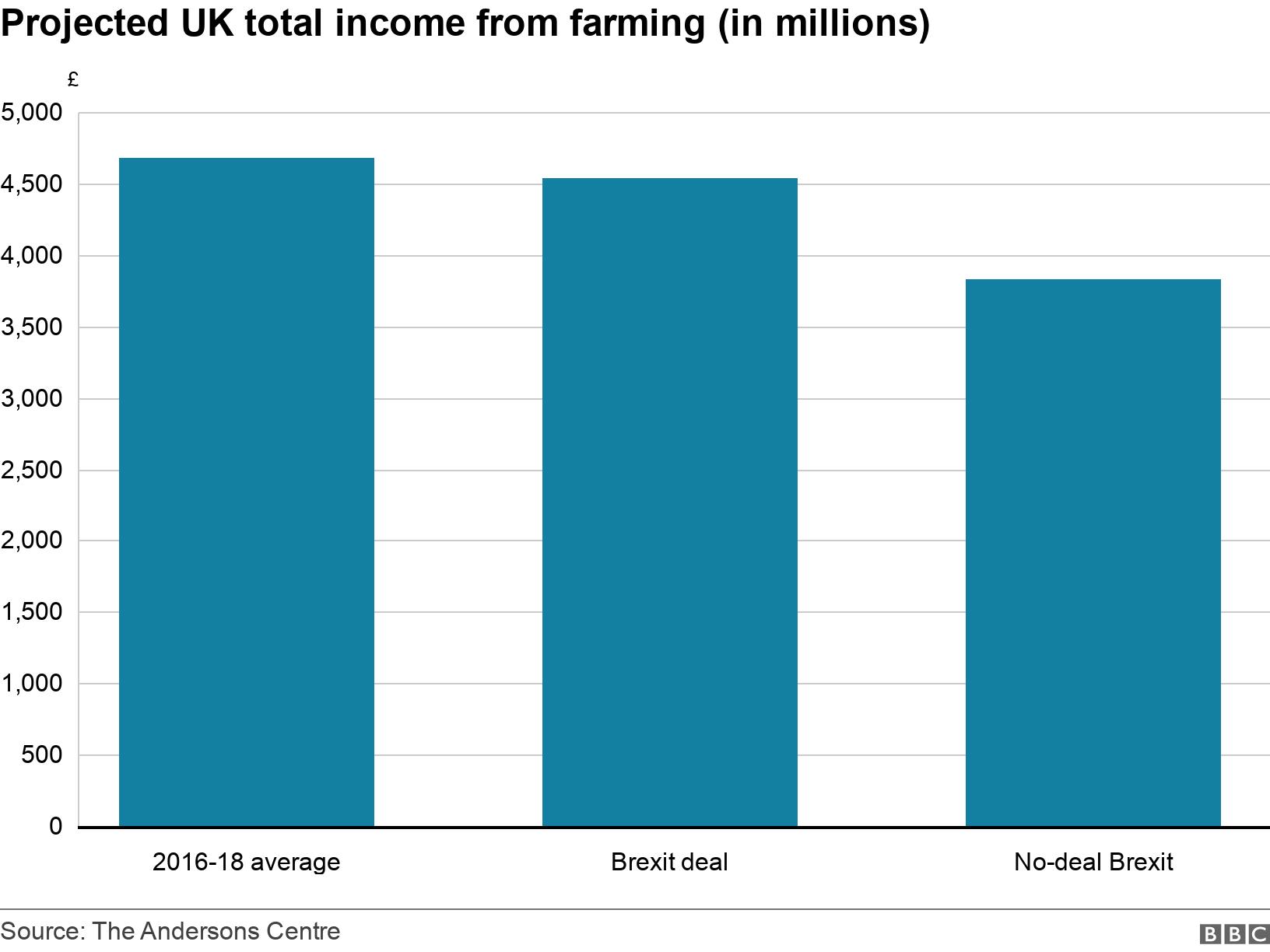

A no-deal Brexit could cost the farming industry £850m a year in lost profits, new research seen by the BBC suggests.

Farm business consultants Andersons said that without government support increasing significantly, some farms would inevitably struggle to survive.

The author of its research described a no-deal Brexit as a greater challenge than the BSE and foot-and-mouth crises.

The government says it will "provide direct support to boost some sectors in the unlikely event this is required".

Read more on the BBC's Focus on Farming here.

'Decimate' industries

Under a no-deal Brexit, farms could have to pay a tariff on goods exported to the EU for the first time.

Lamb and live sheep exports could face tariffs of 45-50%, while trade and farming groups say some cuts of beef could see tariffs of more than 90%.

If European firms suddenly start having to pay more for UK meat, the fear is they could quickly switch to suppliers in other countries.

Other so-called "non-tariff barriers", like extra veterinary and customs checks at the border, could also increase costs to farmers.

Jo and Lindsay Best fear a no-deal Brexit could "decimate both the sheep and cattle industries" in Northern Ireland

"It could wipe out the sheep industry in Northern Ireland," farmers Jo and Lindsay Best, from County Antrim, told the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme.

"A large percentage of our sheep are exported into France and the Republic of Ireland, and the price of feed could go up as well. It could decimate both the sheep and cattle industry here."

Andersons modelled the impact on typical farms, external in different parts of the UK.

Farms already receive more than £3.5bn a year in EU subsidies under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

The government has told farmers those support levels will be maintained until the next general election and that is included in Andersons' calculations.

In the first year after a no-deal Brexit, profitability across the whole industry would fall by 18% - or between £800m and £850m - compared with the 2016-2018 average, its research suggests.

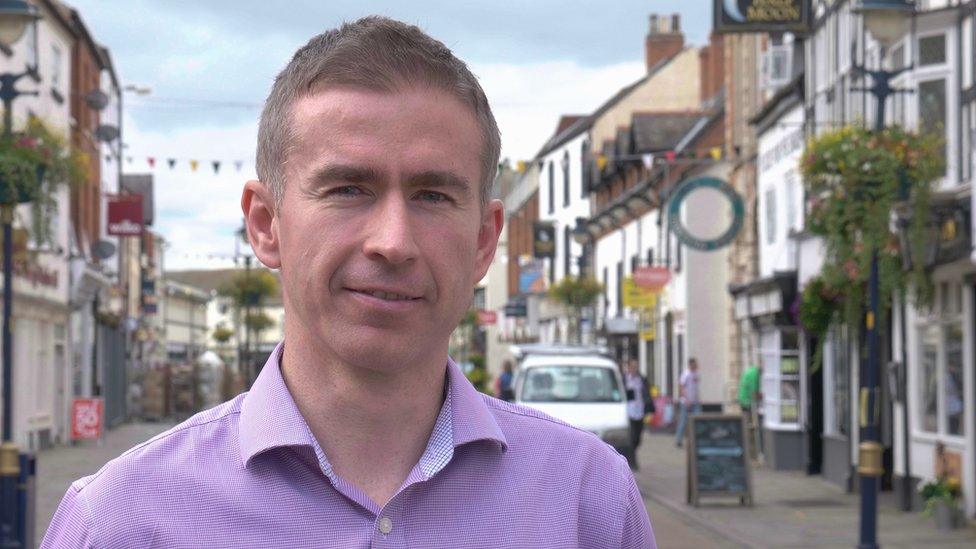

"At the moment a number of farms across numerous sectors are heavily reliant on support," says Michael Haverty, who compiled Andersons' research.

"Many farms are struggling to break even. If they get a hit in terms of profitability of 18%, and for some sectors significantly more, then that has huge implications for the viability of those farms."

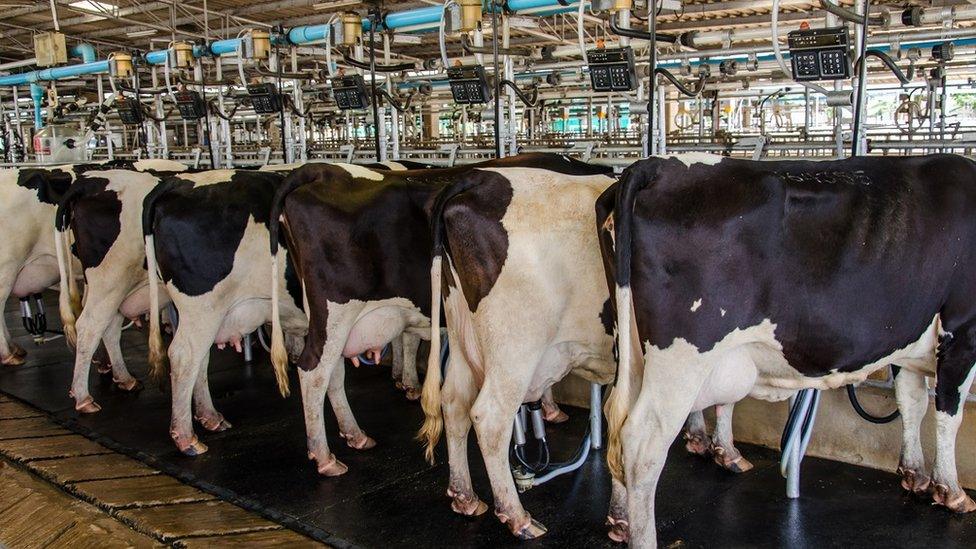

The firm's model shows the profitability of a typical dairy farm in England will fall from 3.4 pence per litre of milk to 0.9 pence per litre under no deal.

In Scotland, the typical dairy farm would struggle to break even, it suggests, while in Northern Ireland it is likely to become loss-making.

Uncertainty 'the biggest challenge'

Under a no-deal Brexit, dairy exports would attract higher tariffs and other restrictions which, it is feared, could lead to an oversupply of milk in the UK and falling prices.

At the same time, tariffs on imports from outside the EU could be cut substantially, meaning British farmers would face competition from low-cost butter and cheese made overseas.

Colin Ferguson, who runs his own herd of 200 dairy cattle on the Machars peninsula in south-west Scotland, said that would be his "biggest concern".

"[Produce from overseas] doesn't need to meet the high welfare or production standards that we conform to, therefore our market gets undermined by cheap produce and the consumer quite rightly will buy the cheapest item on the shelf," he added.

Mr Ferguson - who voted Leave in 2016 - said uncertainty around the UK's relationship with the EU was the "biggest challenge" and had already made it harder to invest in new livestock or machinery.

Colin Ferguson with some of his cattle

"That clarity is vital," he added. "We just need to know what's going to happen."

In the longer term, he is positive about leaving the EU - seeing it as an opportunity to redesign the system of financial subsidies paid to farms in the UK.

Increase in support 'inevitable'

The research by Andersons shows the impact of a no-deal Brexit will not be felt equally across the industry.

Lamb and beef farming are likely to be hardest hit, especially in Wales and Northern Ireland.

Other businesses - like fruit and vegetables, pigs and poultry - could see modest increases in profitability as rivals like Danish bacon attract import tariffs and become more expensive.

That though is dependent on migrant labour remaining available after 31 October.

Michael Haverty says a no-deal Brexit would be "the biggest challenge this industry has faced probably since World War Two"

Mr Haverty said it was "inevitable" the government would have to put in place substantial levels of financial support over a number of years, while farms in some sectors adjust.

"If we look at some of the other key challenges of the past - BSE and foot-and-mouth for instance - they were significant in their own right but perhaps a bit more confined," he said.

"A no-deal Brexit is more encompassing. It's not just within the agricultural sector, it's within the wider economy as well. On that basis it's the biggest challenge this industry has faced probably since World War Two."

The Department of the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs said in a statement: "We have been very clear that once we leave the EU on 31 October, we will replace the Common Agricultural Policy with a fairer system of farm support and our new trade deals must work for UK farmers, businesses and consumers."

It added: "As we have said before, the cash total for farm support will be protected until 2022, even in the event of a no-deal Brexit.

"We will also intervene to provide direct support to boost some sectors in the unlikely event this is required."

How do tariffs work?

If countries do not have free trade agreements, they trade with each other under rules agreed by members of the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Each country sets tariffs on goods crossing its borders. All EU countries share common tariffs because they are all signed up to the customs union.

EU tariffs on most agricultural products can be very high - dairy averages more than 35% and for some meat products, such as lamb, it is more than 40%.

As the UK is still a member of the EU, it applies EU tariffs to goods coming in from the rest of the world, but has no tariffs with the EU itself.

But Brexit will change that.

The UK has said that under a no-deal Brexit most imports would not attract a tariff, in order to keep trade flowing through ports like Dover. But it would have to offer the same reductions to all other countries as well.

Follow the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme on Facebook, external and Twitter, external - and see more of our stories here.

- Published15 August 2019

- Published13 August 2019