Spending Review: What is it and how does it affect me?

- Published

Chancellor Rishi Sunak has announced how much money the government will spend on hospitals, schools and other public services over the next financial year, starting in April 2021.

In his Spending Review, he also unveiled a new set of official forecasts for the economy, which are predicting the biggest economic decline more than 300 years.

How does the Spending Review affect me?

The Spending Review determines how much is spent on public services.

So anyone who ever visits an NHS hospital, or goes to school, or uses roads or any of the other service provided by government will be directly affected.

It's also a chance for the government to deliver on some of the promises it made at the last election, such as improving the economy of less wealthy areas of the UK.

The Spending Review also included details of public sector workers' pay next year.

One million NHS workers and anyone earning less than £24,000 will be given a pay rise. But everyone else, including police officers, fire fighters and teachers, will have a pay freeze,

The chancellor's decisions will affect how much the government borrows next year and beyond. The cost of paying back those debts, or at least paying the interest on them, will fall on future taxpayers for years to come.

Will teachers get a pay rise in the Spending Review?

How has coronavirus affected the Spending Review?

Usually a Spending Review would cover a period of three or four years to give government departments enough certainty to make long-term plans.

The coronavirus pandemic disrupted so many aspects of life this year that long-term planning is particularly difficult.

So the government decided that this Spending Review would only cover the 12 months from April 2021.

Normally the amount of money a chancellor would allocate in a Spending Review would be strictly limited by how much they would be prepared for the government to borrow.

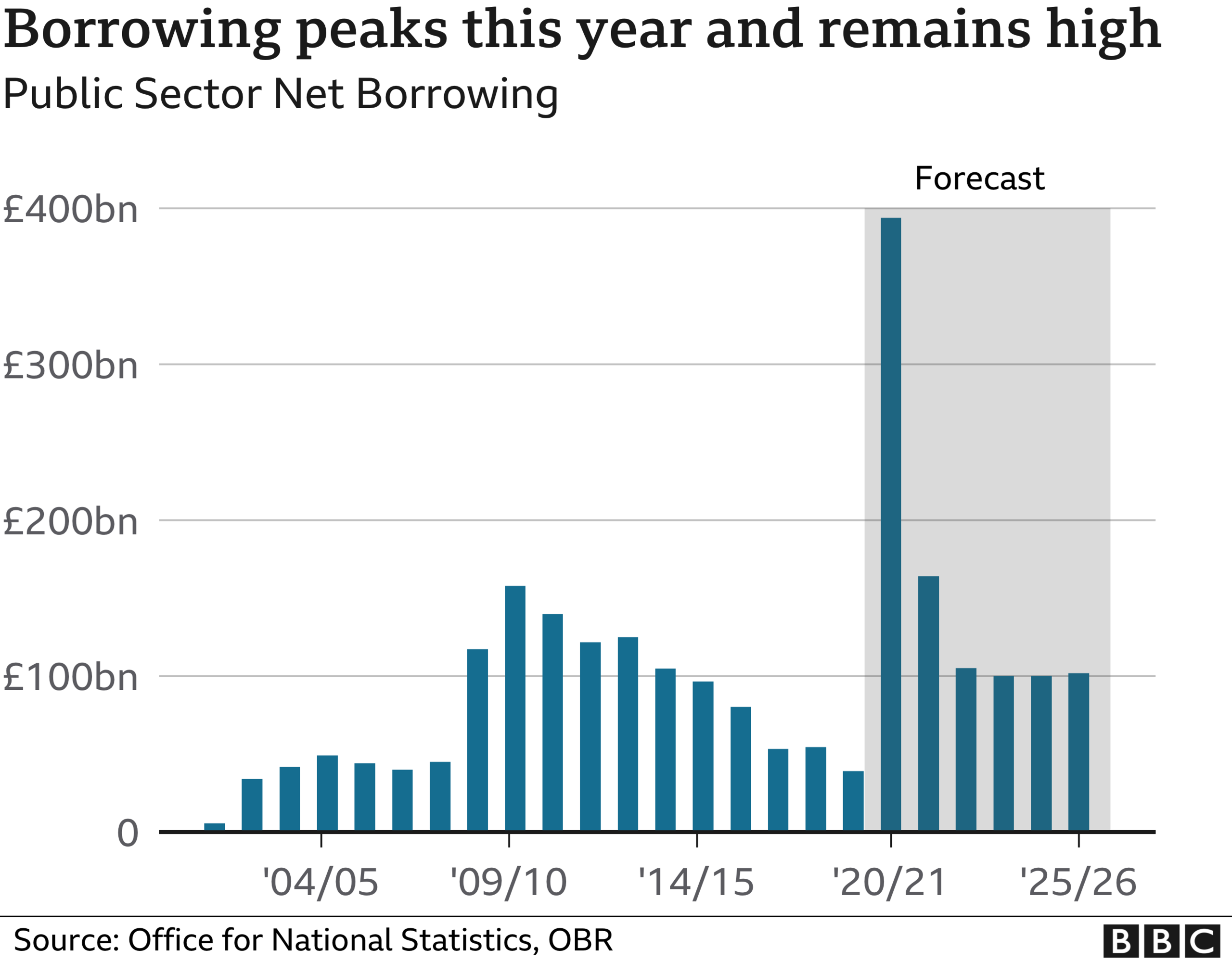

But this year the pandemic has caused government borrowing to skyrocket.

With businesses closed and workers on furlough, the government is taking less money in taxes. And it's spending more than planned on measures to fight the virus and support the economy.

Before the pandemic, the government expected to borrow around £55bn this financial year.

Seven months in, the government has already borrowed £215bn, and the total is expected to hit £394bn this year, the highest level seen in peacetime.

The government can't keep borrowing that amount of money for very long.

So the chancellor has to balance the fight against coronavirus with the need to keep borrowing to manageable levels.

What measures were announced in the Spending Review?

Among the major decisions in the 2020 Spending Review were:

The NHS in England will get an extra £6.3bn to help meet the government's commitment to get the NHS budget to £148.5bn by 2023-24

Schools in England have been promised an extra £2.2bn in 2021-22, taking total spending to £49.8bn

Defence will get an extra £16.5bn over four years

The government's target for overseas aid spending will be cut from 0.7% of national income to 0.5%,

A new £4bn levelling up fund for upgrading infrastructure such as roads

A full list of measures is here.

The government has already announced an increase in defence spending

What did we learn about the state of the economy?

Alongside the Spending Review, the Office for Budget Responsibility, which keeps tabs on government spending, unveiled a new set of government forecasts which were dismal.

It estimates that the economy will shrink by 11.3% this year, the worst figure for more than 300 years.

The unemployment rate will peak at 7.5% next year, with 2.6 million people out of work.

And the long-term damage to the economy will be severe - even in 2025, national income will be 3% lower than expected before the crisis began.

That will present the chancellor with a stark choice in coming years - cut spending, raise taxes, or allow the government to keep on borrowing.

How does the Spending Review affect the rest of the UK?

Many announcements in the Spending Review only apply to England.

Much of government activity elsewhere in the UK is controlled by the devolved administrations - the Scottish government, Welsh government and Northern Ireland Executive.

If the chancellor spends extra money on a service which is covered by devolution, such as education, the devolved administrations get extra money too.

The idea is that a £100 increase in spending per person in England on education, for instance, should be matched with an extra £100 per person for each of the devolved administrations to spend as they choose.

The way money gets allocated is set out by the Barnett formula, named after Lord Barnett, the politician who devised it in the late 1970s.

- Published25 November 2020