Rishi Sunak warns 'economic emergency has only just begun'

- Published

- comments

What you need to know about Chancellor Rishi Sunak's speech – in two minutes

The "economic emergency" caused by Covid-19 has only just begun, according to chancellor Rishi Sunak, as he warned the pandemic would deal lasting damage to growth and jobs.

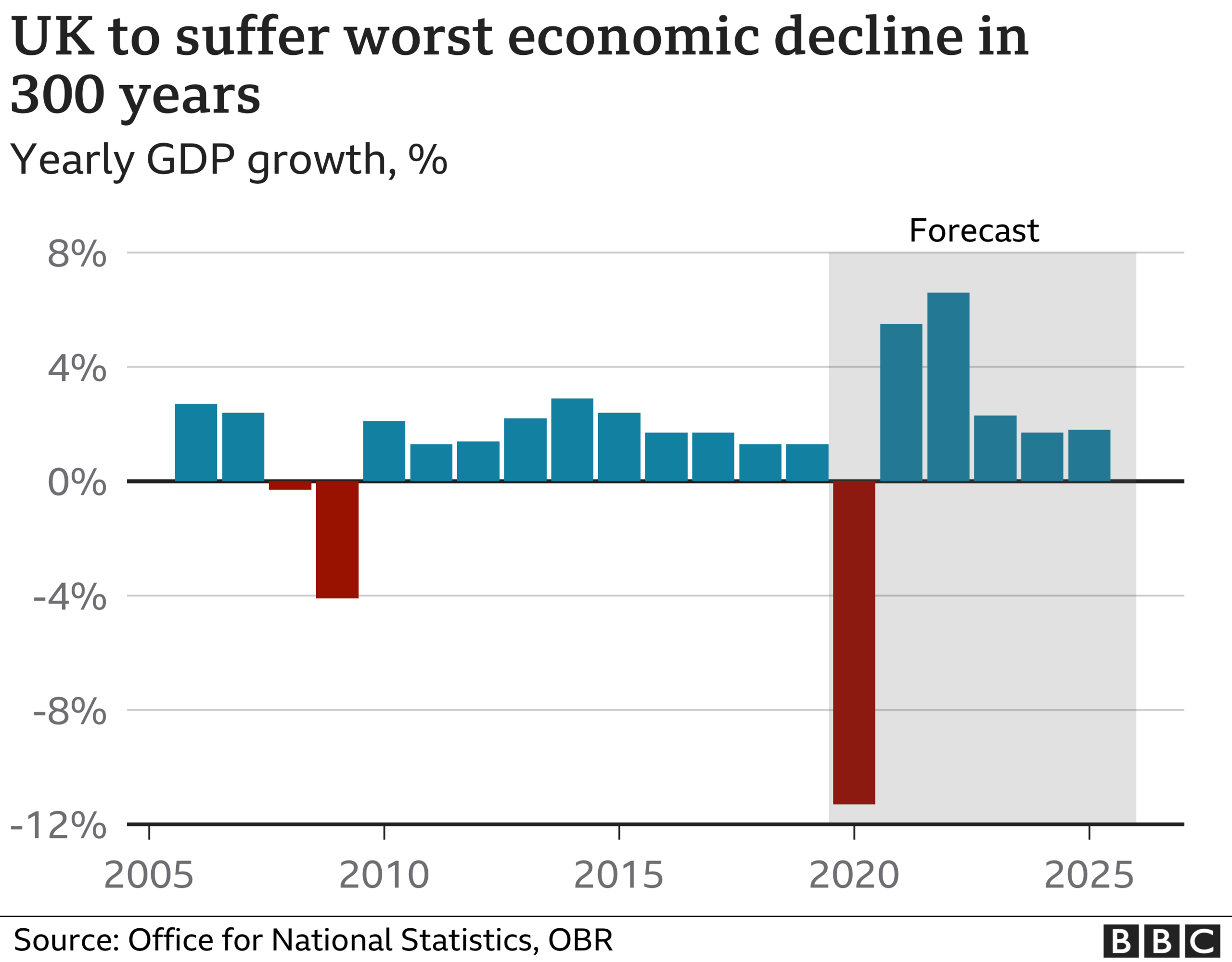

Official forecasts now predict the biggest economic decline in 300 years.

The UK economy is expected to shrink by 11.3% this year and not return to its pre-crisis size until the end of 2022.

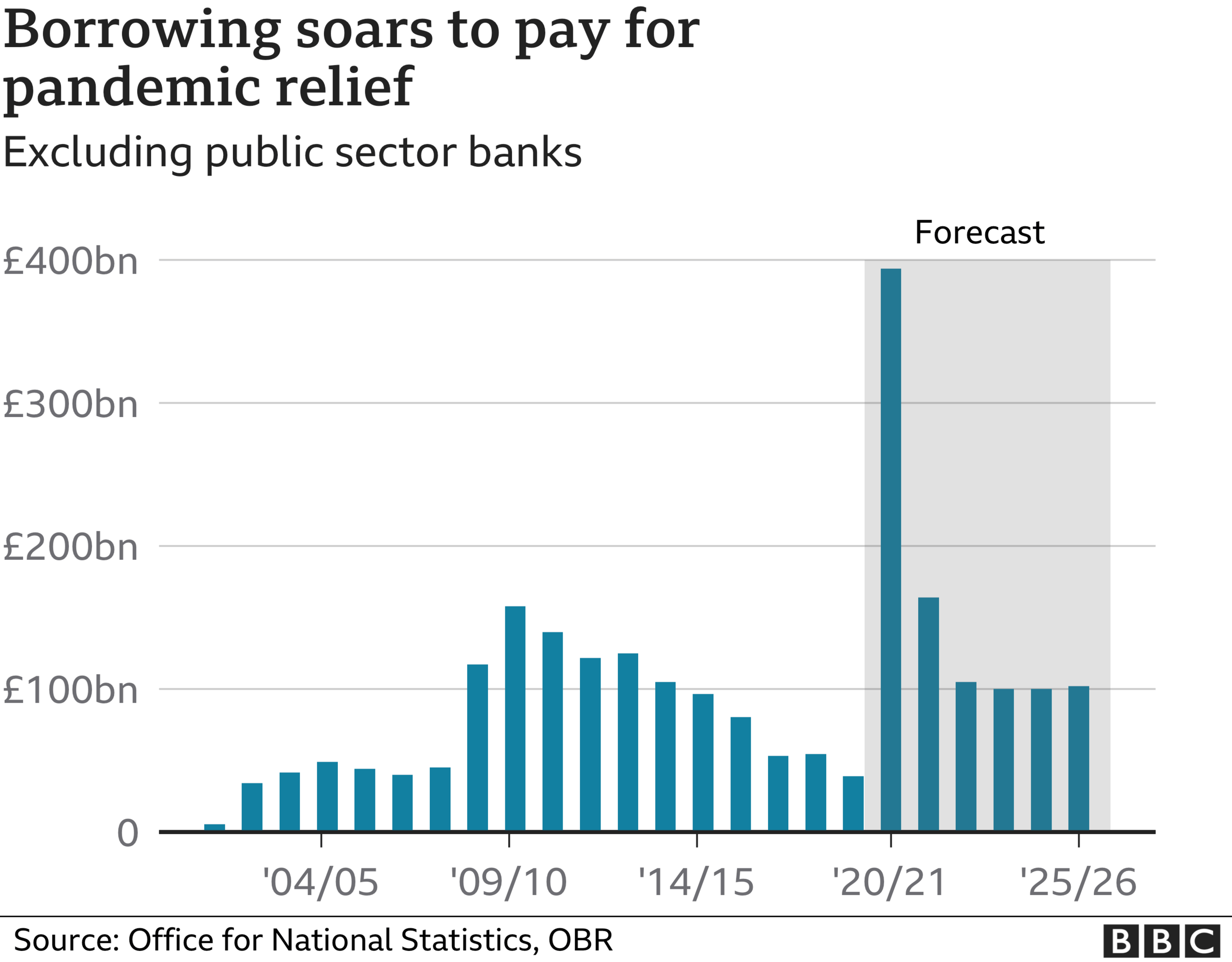

Government borrowing will rise to its highest outside of wartime to deal with the economic impact.

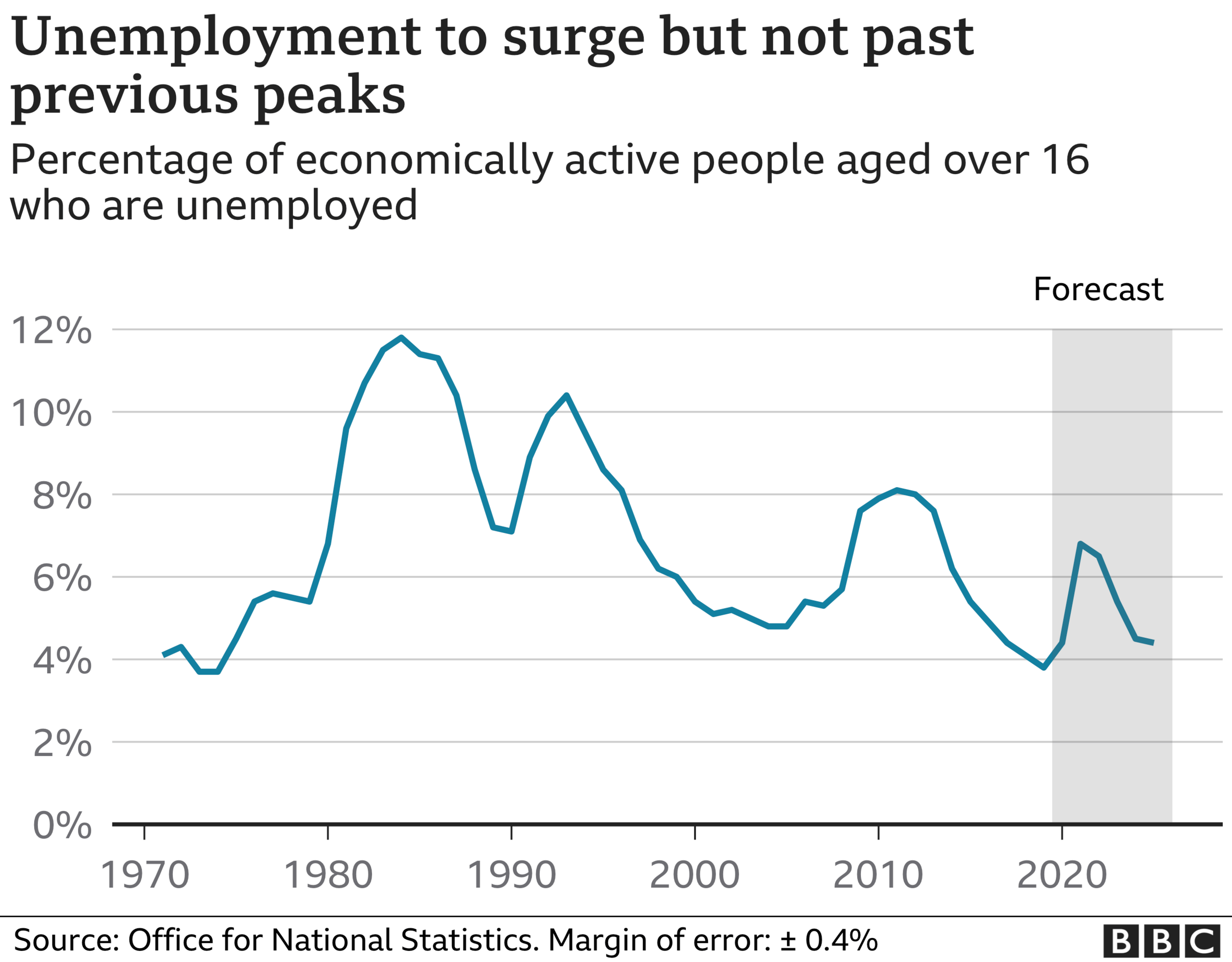

The government's independent forecaster, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) expects the number of unemployed people to surge to 2.6 million by the middle of next year.

It means the unemployment rate will hit 7.5%, its highest level since the financial crisis in 2009.

However, fewer jobs are expected to be lost than predicted this summer.

Setting out his Spending Review detailing how much would be spent on public services, Mr Sunak said the government was dealing with an "economic emergency".

He added: "That's why we have taken, and continue to take, extraordinary measures to protect people's jobs and incomes."

The government has subsidised the wages of employees unable to work due to the pandemic, in an effort to protect jobs.

It said extending these schemes to next March meant 300,000 fewer people would be out of work.

What about public sector pay?

Mr Sunak confirmed that around 1.3 million public sector workers - excluding some NHS staff and those earning less than £24,000 - will have their pay frozen next year.

The chancellor said he could not justify an across-the-board increase when many in the private sector had seen their pay and hours cut in the crisis.

But Mr Sunak said lower-paid public sector workers would be guaranteed at least a £250 pay rise next year.

The shadow chancellor, Anneliese Dodds, criticised the pay freeze.

She said: "Earlier this year the chancellor stood on his doorstep and clapped for key workers. Today, his government institutes a pay freeze for many of them. This takes a sledgehammer to consumer confidence."

Civil servant Robert said he was 'deeply disappointed'

Robert, a 25-year-old civil servant and representative for the PCS Union, said he was "deeply disappointed".

"[Civil servants] have spearheaded the response to the pandemic and worked tirelessly to deliver Brexit. We've stepped up and delivered... and I'd like to be recognised for that."

Having worked for various government departments since graduating from university a few years ago, he says he feels "let down".

What else was announced?

The minimum wage - which has been rebranded as the National Living Wage - will increase by 2.2% - or 19p - to £8.91 an hour, with the rate extended to those aged 23 and over.

Other rates were also increased. From next April, 16 and 17 year-olds will see their pay go up to £4.62 per hour, from £4.55 today.

The UK also ditched its policy of spending 0.7% of national income on overseas aid to help deal with the coronavirus crisis at home.

Mr Sunak said the new 0.5% target - which adds up to about £4bn in savings - will be "temporary".

And millions of retirees will see the future value of their pension cut owing to a planned change in the way payments are calculated from 2030.

How much will this cost?

Mr Sunak said the government had already spent £280bn to help support the economy through the coronavirus.

It will spend a further £55bn next year as part of a package of measures to support the recovery. This includes billions of pounds to help people find jobs.

The UK is expected to borrow £393.5bn this financial year to help pay for economic relief measures.

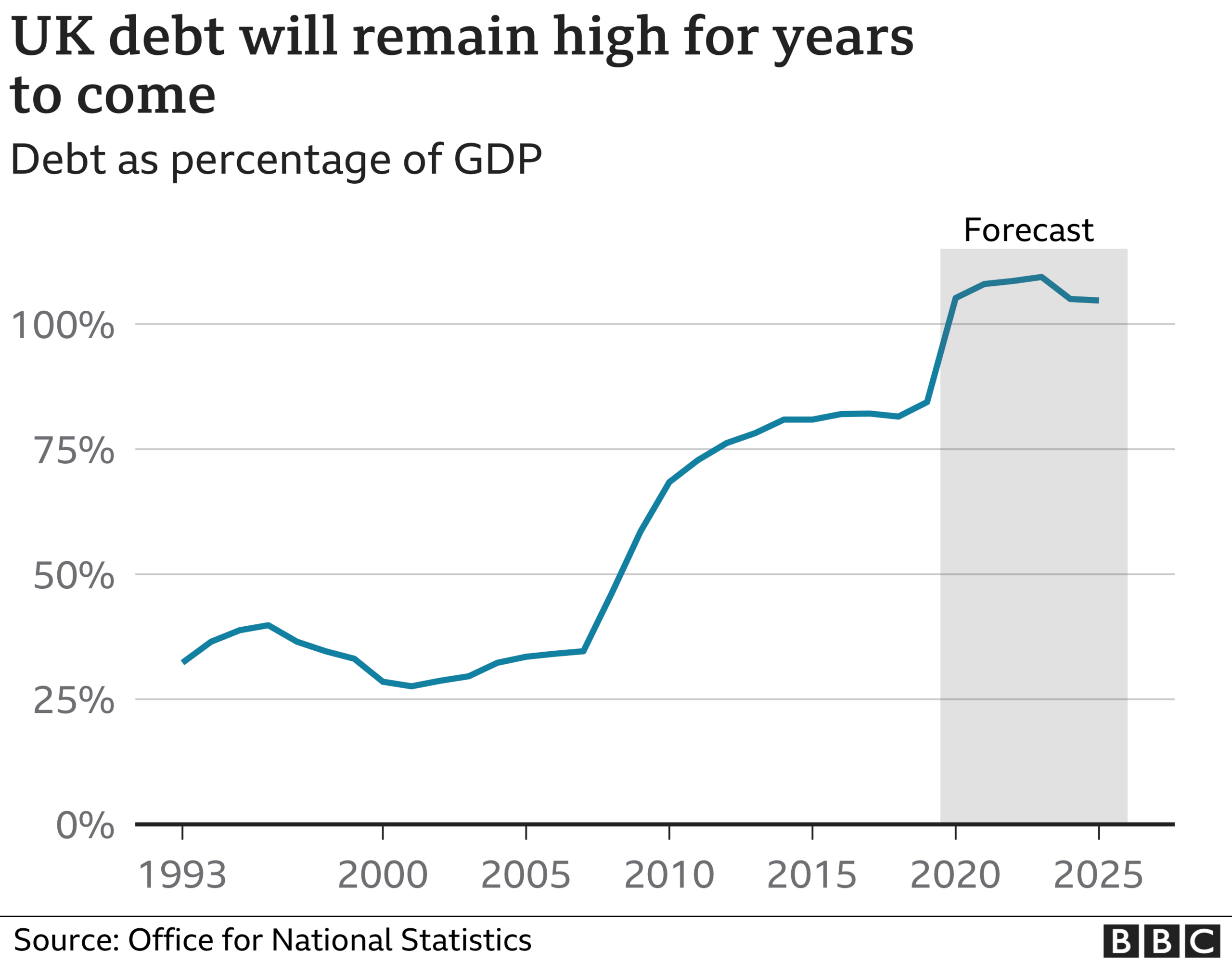

Borrowing is also forecast by the OBR to remain above £100bn-a-year - or 4% of the size of the UK economy - in five years time.

In recent years, the government has been able to borrow easily at very low interest rates, which makes its debt more affordable.

At the moment it pays just 0.32% interest to borrow for ten years.

However, Mr Sunak said long-term scarring meant the economy would be 3% smaller in 2025 than expected in the March budget.

How will the UK get debt under control?

The OBR said the coronavirus pandemic had "delivered the largest peacetime shock to the global economy on record", while recent restrictions across the UK had taken "the wind out of an already flagging recovery".

It said the UK's later and longer lockdown this spring meant it had experienced "a deeper fall and slower recovery in economic activity" than some of its European neighbours.

The independent forecaster also warned that tax rises or spending cuts would be needed in future years to stabilise the UK's growing debt pile.

Richard Hughes, the OBR's chairman said: "The chancellor will need to find £20bn to £30bn in spending cuts or tax rises if he wants to balance revenues and day-to-day spending, and stop debt rising by the end of this parliament."

Is this the end of government support?

Is that the end of it? The official forecasts assume that 2 December spells the end of lockdown, that we remain in the equivalent of Tier 3 restrictions until the spring - and then the vaccine becomes widely adopted in the second half of 2021. Too cautious - or optimistic? If anything, 2020 has taught us that assumptions can last as long as a disposable face covering.

But it'll take longer for economic life to spring back to rude health. Reviving job prospects, investment and consumption will take TLC. Even when the official crystal ball gets misty, in 2025, output is still 3% lower than it was previously expected to be.

And that's without the risk of a no-deal; the OBR says that could mean that output is a further 1.5% by 2025. Some economists think the hit could be greater (indeed, the Governor of the Bank of England says the long term impact of a no- deal could exceed that of a virus).

Rishi Sunak has to decide when to turn off the support to the convalescing economy - and when to start patching up the public finances by firing up tax rises. The extreme uncertainty underlines how fraught - and costly - that decision could be.

What will happen to house prices?

House prices are expected to fall in 2021 and 2022.

The OBR expects a recent revival in the market to end next year when a stamp duty holiday stops in March and more people lose their jobs as government support schemes are pared back.

However, the end of the tax break is expected to contribute to a 3.5% fall in house prices next year and a further 2.6% drop in 2022.

The OBR added: "Despite a steady recovery from 2022 onwards, the level of house prices remains around 17% lower (in 2025) compared to our March forecast."

What about Brexit?

The OBR said the "unresolved nature" of the negotiations between the UK and EU over a Brexit deal had "further clouded" the economic outlook.

It said failure to secure a deal would reduce the size of the UK economy by a further 2% in 2021, with permanent damage to growth and living standards in future years.

Under this no-deal scenario, the economy would not return to the size it was before the pandemic hit until the second half of 2023, while unemployment would peak at a higher rate of 8.3%.