Peloton: 'It's borderline addiction'

- Published

Joanna Sim is part of a passionate Peloton tribe

Joanna Sim is a self-confessed member of the Peloton cult. She gets up at 05:00 for the company's classes. She writes about them, external on her blog for working parents.

She doesn't just like Peloton, she says, she loves it.

"It's almost borderline addiction at this point," she says. Now she's planning to invest.

The company, which sells tech-enhanced exercise equipment tied to streaming fitness classes, raised about $1.16bn as it sold its first shares on the Nasdaq stock exchange on Thursday.

The shares priced at $29 apiece, valuing the firm at more than $8bn (£6.5bn) - a hefty figure in a notoriously fickle fitness industry.

But they tumbled lower as trading began, closing down 11%.

Peloton acolytes such as Joanna say the company has matched exercise to the age of social media, combining the convenience of an at-home workout with the interaction and adrenaline rush of live classes.

The company, which was founded in 2012, has more than 500,000 subscribers. It went live in the UK and Canada in 2018 and in Germany in May. It has started branching out to new areas, offering classes in yoga and strength-training.

High-profile users include Kate Hudson, David Beckham, Leonardo DiCaprio, Michael Phelps, Usain Bolt and more.

Allow Instagram content?

This article contains content provided by Instagram. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Meta’s Instagram cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Participation is expensive. Peloton's stationary bikes cost more than $2,200 (in the UK they start at £1,990) and its treadmills, which it started selling last year, are almost double that. Unlimited access to the streaming classes runs to another $39 a month (£39 a month in the UK).

Despite the price tag, Joanna says she "took the plunge" last year, cancelling her gym membership and buying a bike in the hope it would make it easier to fit in more workouts.

The mother of two, who lives in California and works full-time as a design strategist at software company Intuit, has not been disappointed.

She says the flexibility of the company's programmes, and the "tribe" of fellow riders she interacts with during a regular 05:00 class, have kept her coming back for more, and more.

Her enthusiasm extends to the firm's financial prospects.

"They're going to IPO soon and I'm... all over it," she says.

Money spinner

Peloton made $915m in revenue in its most recent financial year, more than double the year before, which was double the year before that.

But growth has come with costs.

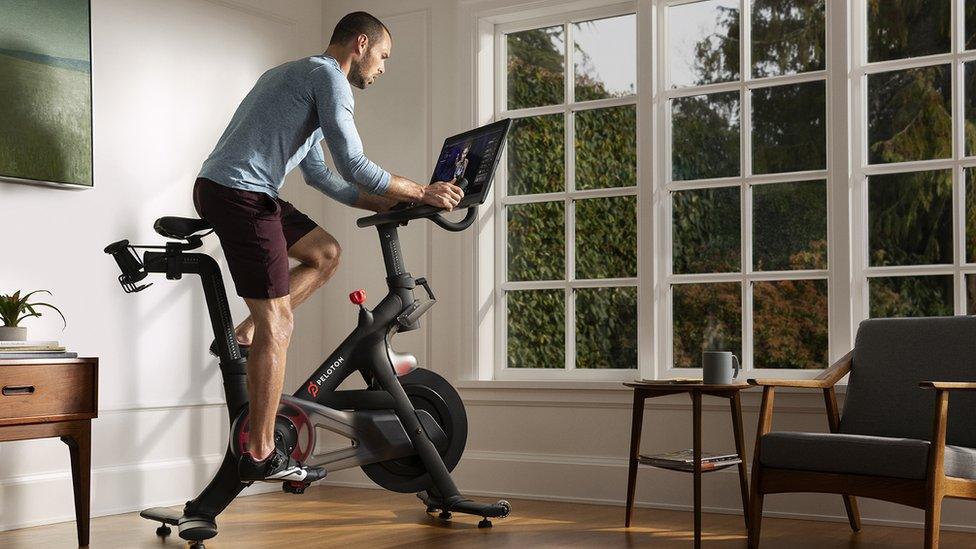

Peloton's tech-enhanced equipment offers live fitness classes at home

Peloton remains unprofitable, losing about $200m last year, as its marketing expense skyrocketed.

In the run-up to its flotation, music publishers hit the company with a $300m copyright lawsuit, accusing the firm of using music for its classes without permission.

And sceptics are asking if the firm, which today relies on big-ticket purchases of equipment, has staying power, given the appearance of lower-cost competitors and fast changing fitness fads.

"It's very difficult to double every year," says Rett Wallace, chief executive of research firm Triton. "Right now, it looks like we're still very much in a growth phase on the hardware but we don't know how long that will last."

'Fitness is difficult'

Other fitness firms testing the public markets in recent years haven't fared particularly well.

The pricey cycling studio chain SoulCycle, which once claimed cachet similar to Peloton, filed flotation papers in 2015.

But the company, a subsidiary of property giant Related Co, dropped those plans last year, citing "market conditions". This summer, the mood soured farther, when owner Steve Ross's fundraiser for President Donald Trump triggered a customer boycott.

YogaWorks debuted on the Nasdaq in 2017, after a growth sprint fuelled by private equity backer Great Hill Partners turned it into one of the largest yoga chains in the US.

Less than two years later, the firm de-listed its shares, amid mounting losses and a warning from the exchange that the stock's price no longer met the minimum threshold.

And it's not just fitness chains focused on live classes that have struggled.

Allow Instagram content?

This article contains content provided by Instagram. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Meta’s Instagram cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Shares in FitBit, which makes wearable fitness trackers, approached $50 in the summer of 2015, when the rapidly growing firm went public. But sales soon slumped and today, the shares trade at about $4.

"Hardware is difficult. Fitness is difficult," says Mr Wallace. "If you rely on the sale of hardware, even Apple shows us that if you're not reinventing your hardware all the time, your life can become difficult."

"Peloton seems to have established a brand for itself and has a very loyal user base," he adds. "We'll see if that sticks."

Joanna says she's heard the doubts but her experience convinced her that Peloton has a long ride ahead of it.

"Given the amount of content that they're pumping out and the leadership that they have... I have full confidence," she says.

- Published12 August 2019