How would a 32-hour week work in practice?

- Published

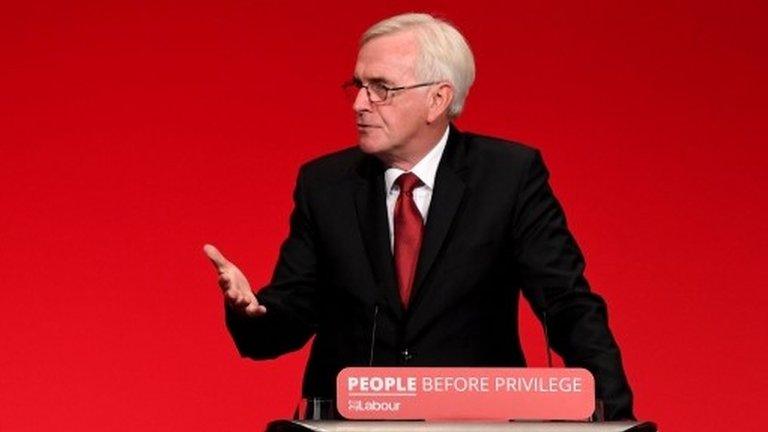

On the face of it, John McDonnell is offering quite the deal: a reduction of the daily working week for all by almost a day, without a pay cut.

A 32-hour week eclipses even the reversed 35-hour week policy of the French Socialists of two decades ago.

It appears, at first glance, to go further than the report on the subject, written by cross-bench peer Robert Skidelsky and commissioned by the shadow chancellor, which was published earlier this month.

That report said imposing a four-day week would not be "realistic or even desirable".

But it is important to state from the off that this is not a French-style cap on hours. It would not be directly enforced on businesses.

It is an essentially political commitment, to attempt to massage labour market institutions towards a considerable reduction in the hours worked in the average working week over a decade. This would be a very significant change.

In an average week, the total of all hours worked by the entire workforce is 1.05 billion. If you assumed the workforce remained the same, then this policy would see total hours worked cut by around 100 million hours.

In and of itself, it would have a significant effect on the economy. But the opposition argue not just that the policy will not cost the economy, but that individual workers will not get a pay cut. How is such a free lunch, indeed tens of millions of such lunches, possible?

It requires an epic increase in productivity, how much each worker actually produces, something that has eluded the UK economy.

Business organisations fear that this is the cart before the horse, requiring huge capital investment.

The opposition are essentially trying to grab the benefits of a future decade of technological advancements towards workers, rather than business owners.

Wage bargaining

That said, this does not seem hugely enforceable. The target is an average across the economy, which will only be revealed after the event in national statistics.

The compulsory element here will be a new Working Time Commission, modelled on the minimum wage-setting Low Pay Commission, which will recommend increases in holiday entitlement from the current 28 days, if the reduction in working hours is not being met.

Companies will be obliged to take part in sector-by-sector legally binding wage bargaining with unions.

And that really is the point of this: providing the muscle of government for a hugely restored role for the unions to strike better working time deals for workers. But Labour also say they want higher wages.

Businesses will argue that the inevitable result of this will be lower numbers of actual jobs. There could also be a significant effect on labour-intensive public services, such as social care and the NHS.

Some of these issues are acknowledged by Lord Skidelsky. The average hours worked per week by British full-time workers has barely fallen over three decades - by just one hour a week.

The shadow chancellor wants to communicate that this is not an inevitable economic fact of life, that government can fundamentally act to change such patterns. But they have chosen not to go with the most coercive form of this type of intervention.

- Published23 September 2019