On the inside of a hacking catastrophe

- Published

David Rimmer says firms must consider the impact of data breaches on employees

In early September 2017 David Rimmer was on the final day of a corporate get-together in the US, organised by Equifax, the giant financial firm he worked for.

It is one of the world's biggest credit score agencies, and Mr Rimmer was the chief information security officer (CISO) for Europe.

At the conference centre, he and a handful of other staff were called aside by the global chief security officer. "[He] told us 'there's something I need to tell you and you're going to need to be here indefinitely for the next couple of weeks'," Mr Rimmer explains.

"In that meeting, where external counsel [lawyers] were also present, some of us were told 'if you tell anyone else about this, you'll be fired on the spot and walked off-site'."

It was then that the significance of the breach and the consequences for him and the IT security team began to sink in.

"The impact of knowing something like that, the scale of what happened and not being able to talk to anyone about it is huge."

Immediately after the breach was discovered, only around 50 people from the 11,000 person company knew about it - just senior members of the information security team, some senior executives and people involved in the incident response process.

Cyber-criminals had accessed customer data such as social security numbers, birth dates and credit card details.

Ultimately the breach affected at least 147 million people in the US, as well as 14 million UK citizens and 100,000 Canadians.

The small team held discussions in a war room in Atlanta where they worked alongside outside experts to investigate the incident and put extra controls in place.

This added pressure to the 50-person team to resolve issues, while also isolating the group from the rest of the business.

Immediately after the breach was discovered, only around 50 staff in Equifax knew about it

"I'm sure everyone in the team felt responsible for what had happened, even though this was actually the result of years of corporate decision making on budgets and priorities. There was one member of our team who had worked for Equifax for 40 years, so the personal impact was staggering - there were many people sat at their desks on the verge of tears," Mr Rimmer says.

One week after Mr Rimmer and his team found out about the breach, Equifax published a press release detailing a "website application vulnerability" that malicious hackers had exploited.

"For the first week there was nobody standing up for the security team, clarifying that this is a corporate responsibility and it's not down to individual security professionals," he says.

The details becoming public had a further demoralising effect on staff, who were criticised on social media and in the press by their peers and others within the industry.

"The CISO was attacked for having a music degree even though this was 30 years ago when cyber-security wasn't a known concept. A middle manager on the security team was served with lawsuit papers directly, not via Equifax, while another employee had death threats on social media because he was identified as working for Equifax, so there was a disproportionate personal impact to some of those people who were singled out," says Mr Rimmer.

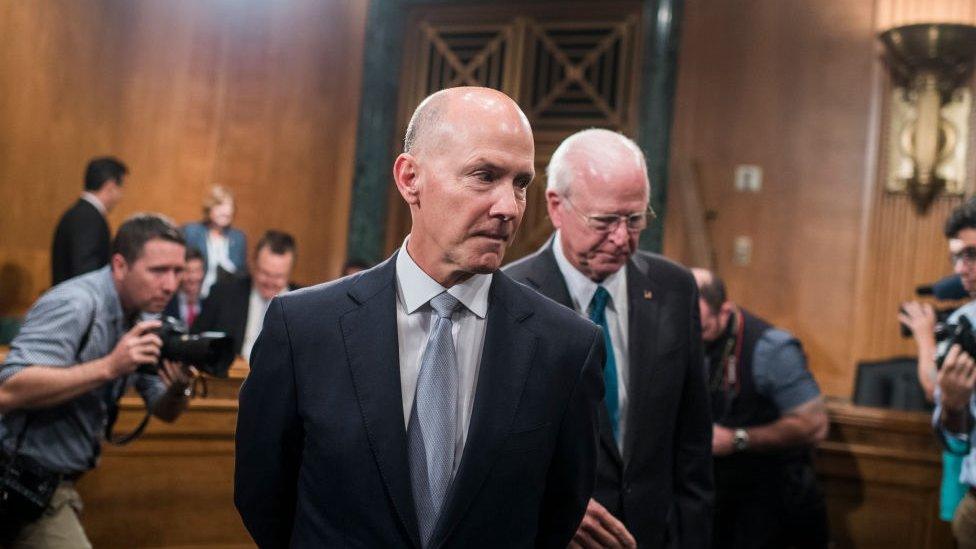

Richard Smith stepped down as chief executive of Equifax following the data breach

But that was not all. Chief executive Richard Smith, chief information officer David Webb and chief security officer Susan Mauldin all stepped down from their roles, causing further disruption.

Russ Ayers took over from Ms Mauldin in an interim role, but while Mr Rimmer praised Mr Ayers for his leadership qualities, he said that the fact that Mr Ayers had to go to Congress to testify in front of the US government meant that he couldn't provide the complete support that the security team required at that time.

"It was a really tough, isolating time with very little physical leadership, a lot of people feeling personally responsible and a lot of people feeling the pressure and not able to talk to anyone about how they were feeling."

While he understands why organisations would want to keep an issue like this between a small team of employees, he believes more needs to be done by employers to take into account the mental health of staff.

"There needs to be a big enough group who can talk to each other about the pressure they're under rather than a few people carrying the weight of the world for everyone. Companies need to recognise when they do planning exercises for security breach responses that they have a duty of care to security employees. Bringing in third parties or throwing money at the problem doesn't help - it exacerbates the problem by increasing the workload on the same staff," he says.

The majority of the 11,000 staff first heard about the incident through the news or after being told by a client or family member. Mr Rimmer believes employers also have a duty of care to employees within the wider business.

"Even if their roles had nothing to do with the incident, they would have felt distanced and almost tainted by association with Equifax but they had to get on with their jobs as usual," he says.

This would also have had a detrimental effect on the employee's effectiveness, as they would have to catch up on what the data breach meant for their part of the business.

Equifax agreed to pay up to $700m as a result of the breach

"It wasn't just about security; IT was doing remediation, the legal team had to deal with customers, sales people had to manage relationships and restore trust, and almost every single part of the business stood still. Although the company will focus on restoring sales and brand perception, they also need to focus on morale and the health of staff across the entire business," he says.

Equifax agreed to pay up to $700m (£561m) in relation to the breach as part of a settlement with US regulator the Federal Trade Commission. It was also fined £500,000 by the UK's Information Commissioner's Office.

An Equifax spokesperson says: "We have made significant progress since the incident to enhance our security and technology operations. We have hired highly qualified Chief Technology and Chief Information Security Officers reporting directly to the CEO, as well as nearly 1,000 full-time IT and security professionals.

"In addition, we have increased our technology and security spending by an incremental $1.25 billion between 2018 and 2020, and we will continue to invest heavily to transform our technology and security to industry-leading capabilities."

However, Mr Rimmer believes that companies should not only focus on the financial consequences of breaches, and instead consider the human impact.

"Equifax spent millions responding to the breach, but that turned into people from the security team working overtime, on 36 hour shifts, and that's the hidden cost of the breach that no one has gotten near to quantifying so far," he says.

According to Simon Ashton, a business psychologist working at Phoenix Leaders, employers should provide adequate training to ensure that their staff feel confident in their skills and abilities to deal with the scenario by using role-playing data breach simulations.

"Once the situation is under control, employers should provide appropriate support so staff are able to discuss how they felt in that situation, what they learnt and what they might do differently next time. This reflection time is important, so staff have the opportunity to understand how they might behave differently in future events," he says.