Why is the world's financial plumbing under pressure?

- Published

We don't always notice vital infrastructure until something goes wrong.

So it was at Citibank in London in the 1960s.

On the first floor, payment instructions were inserted into a canister and sent upstairs via vacuum tube. On the second floor, a team confirmed the transactions and sent their authorisations back down the pipe.

One day the payments department on the first floor realised it wasn't receiving the authorisations it needed. Someone was sent upstairs, where the confirmation team had been idly wondering why all was quiet.

It turned out that the vacuum tube had become blocked.

Pneumatic tube systems were a common sight in many banks and financial companies which needed to send paperwork or small packages over a short distance

Citibank's payment processing operations were duly restored with the assistance of a chimney sweep.

Confirming large financial transactions is hard. It is even harder across national or international borders. Since the development of the telegraph in the first half of the 19th Century, sending instructions has been quick enough.

But quick does not necessarily mean foolproof, as Frank Primrose, a Philadelphia wool broker, was to realise.

In June 1887, Mr Primrose sent a message to his agent in Kansas about buying wool. Because the Western Union telegraph company charged by the word, the message was in code to save money.

A Western Union messenger delivering a telegram, circa 1900

It was supposed to say "BAY ALL KINDS QUO", meaning "I've bought half a million pounds of wool".

But it actually read "BUY ALL KINDS QUO", which the Kansas agent understood as an instruction to "Please buy half a million pounds of wool".

Primrose lost $20,000 - several million dollars in today's terms.

And Western Union wouldn't compensate him, because he could have paid a few cents extra for the message to be verified - but had not.

Clearly, there was a need for a way to send financial information more reliably than through a vacuum tube and more securely than via telegraph in an easily-mistranscribable code.

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that helped create the economic world.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen to all the episodes online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

For decades after World War Two, banks used telex machines, which made efficient use of telegraph lines and allowed users to type a message somewhere and have it printed on the other side of the world.

But the need to make sure that messages were secure and accurate added enormous complexity.

Banks hired former military signalmen to operate their telex machines, and used tables of cross-referenced codes to check and recheck what was being sent.

Telex was a vital tool for sending messages between businesses in the years after World War Two

One veteran recalled the laborious complexities of the task:

"For every single telex that was sent, you had to manually calculate what this telex test key was. When you received the tested telex, you had to do the reverse calculation to make sure the telex hadn't been tampered with during transmit and receive cycles. It was incredibly prone to human error."

By the increasingly global 1970s, the telex system was groaning under the strain. Especially in Europe, the need for a better solution - one that could work smoothly across borders - was becoming acute.

Committees were established, arguments raged, progress was glacial. Then an American bank started strong-arming everyone into using its own proprietary system, called Marti. This was, as they say in Europe, "insupportable".

Many banks feared becoming locked in to any standard that was owned by a rival. So they got their act together through a new organisation, Swift - the Society for Worldwide Interbank Telecommunication, external.

Swift was a private company, with its headquarters in Brussels and run as a global co-operative venture, initially between 270 banks across 15 countries. The first Swift message was sent by Prince Albert of Belgium on 9 May 1977 - and the Marti system closed down the same year.

Swift simply provided a messaging service, using a standardised format that minimised errors and dramatically simplified proceedings. The computing company Burroughs installed Swift's dedicated computers and connections in Montreal, New York, and 13 European banking centres. Each nation's banks would plug into those central hubs.

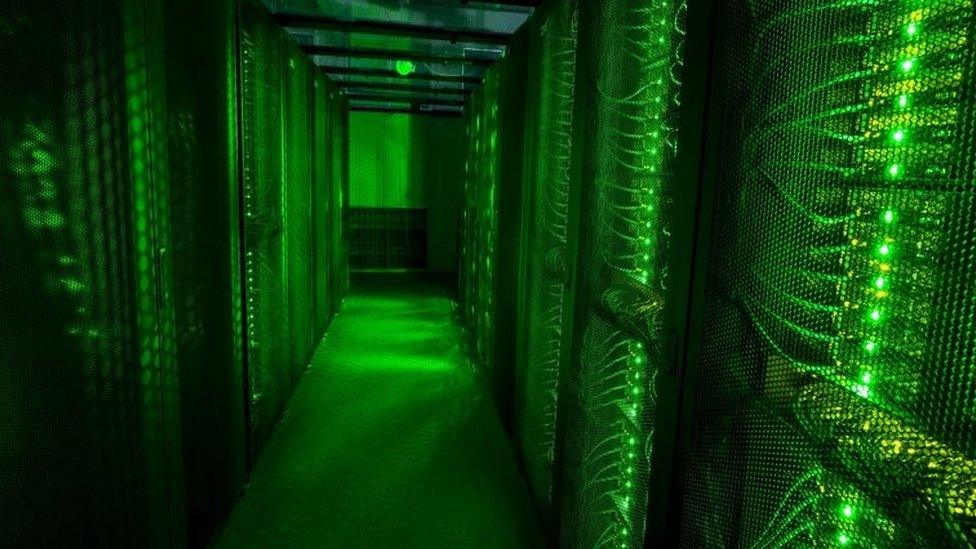

The underlying hardware and software continues to change, transmitting and storing 7.8 billion highly sensitive cross-border banking instructions last year. More important than any particular technology is the co-operative structure of the institution, through which more than 9,000 member banks and financial institutions currently agree standards and resolve disagreements.

Hacks, outages and other problems have occurred - often the result of weaknesses in the systems of banks from smaller or poorer nations.

Yet they remain rare enough for Swift to seem indispensable. The organisation itself would prefer to stay under the radar, a humble part of the financial pipework, operating out of a lakeside office in the sleepy town of La Hulpe, near Brussels.

More things that made the modern economy:

But having largely solved one problem, Swift may have created another.

It is so central to international banking that it is a tempting tool for the 800lb gorilla of the world economy, the US government.

Want to track terrorist financing? Examine the Swift database. Want to destroy the Iranian economy? Tell Swift to deny access to their banks. After all, as any London chimney sweep can tell you - financial pipework can be blocked.

Swift has found itself unable to resist direct orders from the US, even when the EU disagrees. Swift isn't interested in geopolitics, but geopolitics is interested in Swift.

Political scientists Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman see the argument over Swift as an example of what they call "weaponised interdependence" - the big players in the global economy using their influence over supply chains, financial settlement and communications networks to monitor and punish wherever they wish.

The US's blacklisting of the Chinese telecoms firm Huawei is another example, but it isn't a completely modern tactic.

Huawei equipment is used in fast 5G mobile networks around the world

In 1907, after a severe banking crisis had rocked the US and left the British financial system largely intact, British strategists took note.

The UK was losing ground as a manufacturing economy, but as a financial hub it remained supreme. The City of London sat at the centre of a web of banks, telegraph lines and the deepest insurance market in the world. The thinking was that in a war, Germany's banks could swiftly be crushed by financial shock and awe.

Spoiler alert: the plan did not work.

But that historical parallel is unlikely to frighten the US. It will keep a firm grip on the pressure points of the international economy - including the Swift messaging system.

For an organisation that was galvanised as a response to pushy Americans, that is quite a kink in the financial pipe.

The author writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen to all the episodes online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published15 November 2019

- Published8 June 2019

- Published17 April 2017

- Published13 May 2016

- Published25 April 2016