How credit cards changed the way we spend

- Published

The clue is in the name: credit. It means belief, trust.

If you're a shopkeeper, who do you trust to repay a debt? For most of history, only someone you knew personally, which was fine since most of the people you encountered would be from the same small community.

But as cities boomed, things became more awkward.

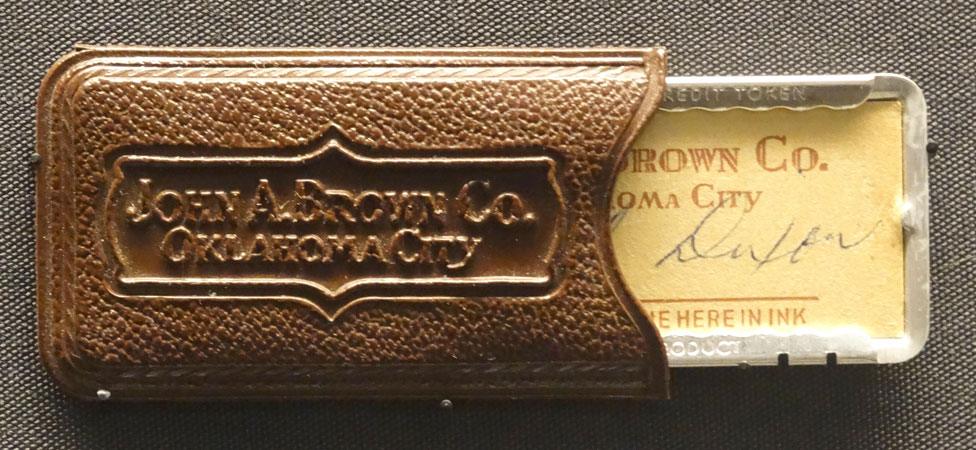

Large department stores couldn't rely on employees to recognise every customer by sight. So retailers issued tokens to trusted customers - special coins, key-rings, and in 1928, even objects resembling dog tags called "charga-plates".

"Charga-plates" allowed customers to take goods and settle their bill at a later date

Show one of those, and a shop assistant who didn't know you would happily let you walk out of the store with an armful of goods you'd not yet paid for. Some of those credit tokens became status symbols in their own right.

In 1947 came the first token that allowed someone to get credit not just from a single store, but from a range of stores: the Charg-It. Admittedly, this worked only within a two-block area of Brooklyn.

But then, in 1949, came the Diners Club card, aimed at the travelling salesman.

Diners Club co-founder Frank McNamara spotted a lucrative gap in the market

It would let him (and it was usually him) buy food and fuel, rent hotel rooms, and entertain clients at a network of outlets around the United States.

And it took off: 35,000 people subscribed in the first year, as the company rushed to sign up hotels, airlines, petrol stations and car hire firms.

In the 1950s came the American Express charge card, and credit cards set up by banks.

Overcoming inertia

Bank of America's imaginatively named BankAmericard would eventually become Visa. Its rival, Master Charge, became MasterCard.

But the early credit cards had two big problems to solve.

One was chicken-and-egg: retailers wouldn't accept the cards without significant consumer demand. Conversely many customers couldn't be bothered to sign up unless plenty of retailers would take them.

A customer pays with an American Express card in a cutlery shop in Manhattan, circa 1955

To overcome the inertia, in 1958 Bank of America experimented by simply mailing a plastic credit card to every single customer in Fresno, California - 60,000 of them.

Each card had a credit limit of $500 (£380), no questions asked - closer to $5,000 (£3,800) in today's terms.

This audacious move became known as the Fresno Drop. The bank took losses, of course, from delinquent loans, and outright fraud by criminals who simply stole the cards out of people's mailboxes.

But the Fresno Drop was quickly emulated. The banks swallowed the losses, and by the end of 1960, Bank of America alone had a million credit cards in circulation.

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations which have helped create the economic world in which we live.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

Listeners were invited to vote for the 51st Thing That Made the Modern Economy from a shortlist of six inventions: glass, GPS, the pencil, irrigation, spreadsheets and credit cards.

The other problem was inconvenience. Pull out a credit card and the shop assistant would have to phone up your bank and chat to a teller to get the transaction approved.

But new technologies helped to make the process of spending ever more painless.

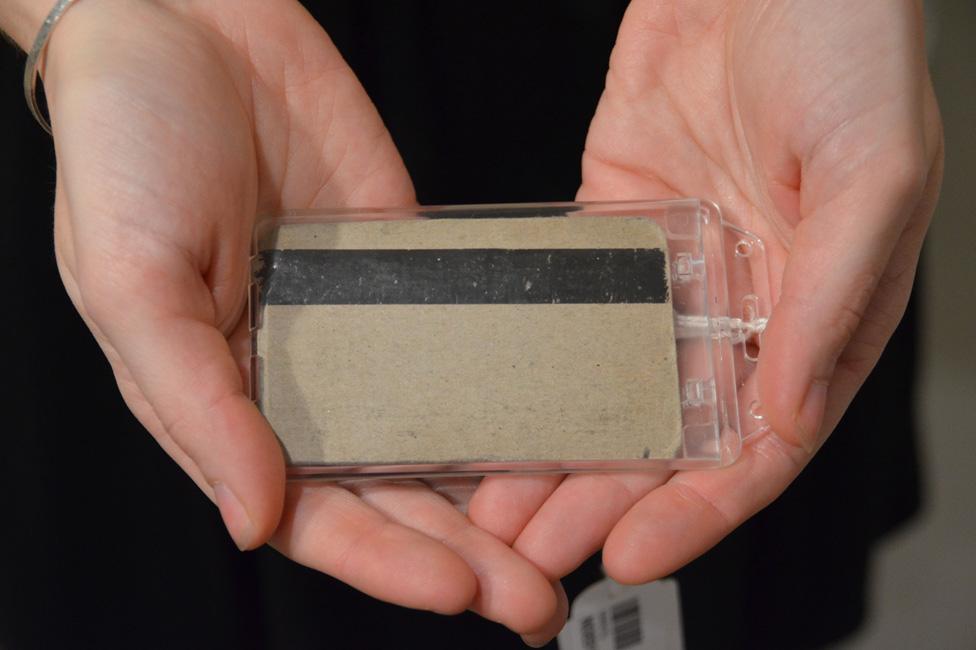

Chief among them was the magnetic strip - originally developed in the early 1960s by Forrest and Dorothea Parry for use on CIA identity cards.

Forrest was an IBM engineer who came home one evening with a plastic card and information encoded on a strip of magnetic tape, trying to figure out how to attach one to the other. His wife Dorothea, who was ironing at the time, handed him the iron and told him to try it.

IBM made two prototype cards with a magnetic strip in the late 1960s

The combination of heat and pressure worked perfectly, and the magnetic strip was born.

Thanks to the strip, you could now swipe a Visa card in a shop. The shop would send a message to its bank, which would send a message to the Visa network computers, and the Visa computers would send a message to your bank.

Cultural shift

If your bank was happy to trust you to repay, nobody else had to worry. The digital thumbs-up passed all the way back through these computers to the shop, which would issue a receipt and let you walk out of the door with your stuff. The whole process took just a few seconds.

So the credit card spread everywhere - and anyone could tap into a network of trust that was once the preserve of upstanding members of a tight-knit community.

It was a huge cultural shift. There was no need to genuflect to a bank manager as you begged for a loan and explained what you wanted it for.

You could spend on anything, and roll the debt over again and again until you were ready to pay at your own convenience - as long as you didn't mind paying interest rates that could easily be 20% or 30%.

More from Tim Harford:

But having such effortless, impersonal credit on tap might be doing strange things to our psychology.

A few years ago, two researchers from MIT, Drazen Prelec and Duncan Simester, ran an experiment, external to test whether credit cards made us more relaxed about spending money.

They allowed two groups of subjects to bid in an auction to buy tickets for popular sports fixtures. These tickets were valuable, but exactly how valuable wasn't clear. One group was told they had to pay with cash - but not to worry, there was an ATM around the corner if they won.

The other group was told that only payment by credit card would be accepted. There was a striking difference in the results: the credit-card group bid substantially more for the tickets, more than twice as much in the case of a particularly popular match.

The death of cash?

That matters, because in some places cash is fast becoming obsolete.

In Sweden only 20% of payments at shops are made with cash - and just 1% of total spending by value is via cash.

Signs like this are becoming increasingly common in Sweden

Back in 1970, a BankAmericard advertising slogan had been, "Think of it as money."

Now, for many transactions, physical money won't do: an airline or a car hire firm or a hotel wants your credit card, not your cash. In Sweden the same is true even of coffee shops, bars and sometimes market stalls.

Credit cards can - used wisely - help us manage our money. The risk is that they make it simply too easy to spend money - money we don't necessarily have.

Rotating credit - that distinctive feature of a credit card - is now around $860bn (£656bn) in the United States, more than $2,500 (£1,900) for every American adult.

In real terms, it's expanded four-hundred fold in 50 years.

And a a recent study by the International Monetary Fund, external concluded that household debt - the kind of debt credit cards make it easy to accumulate - was the economic equivalent of a sugar rush.

It was good for growth in the short term, but bad over a three to five year horizon - as well as making banking crises more likely.

If you ask people about all this, they worry.

Faced with the statement "credit card companies make too much credit available to most people", nine out of 10 Americans with credit cards agree. Most of them strongly agree. Yet when they reflect on their own cards, they're satisfied.

We don't trust each other to wield these powerful financial tools responsibly, it seems.

But we do trust ourselves. I wonder if we should.

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast. Listeners voted for the credit card to be the 51st Thing That Made the Modern Economy from a shortlist of six inventions.

- Published28 October 2017

- Published24 October 2017

- Published12 September 2017

- Published30 August 2017

- Published26 May 2017

- Published27 June 2016