How to make phone batteries that last longer

- Published

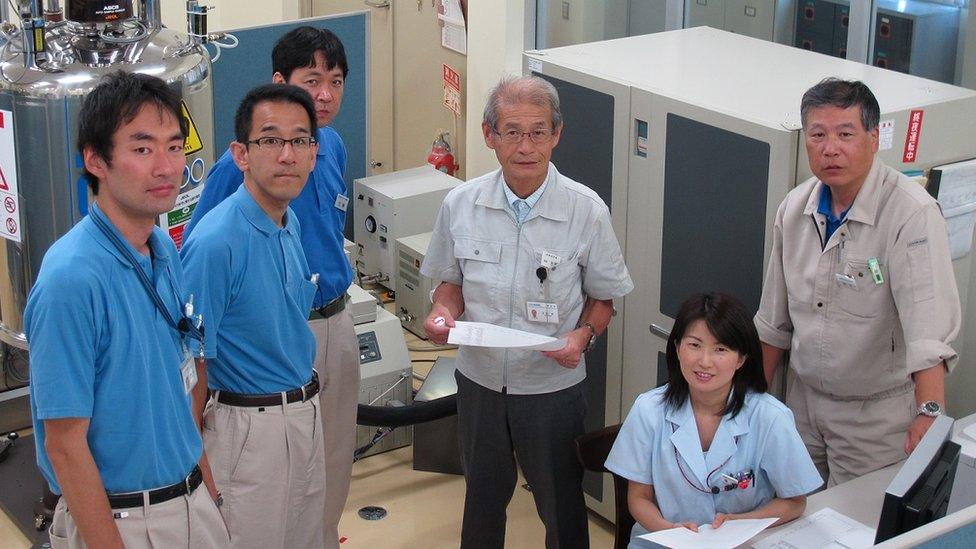

Professor Akira Yoshino (centre) won the 2019 Nobel Prize in chemistry

When Professor Akira Yoshino was developing a new battery technology in his laboratory in the early 1980s, he didn't think it would amount to much.

"At the time, we thought it mainly would be used in 8mm video cameras," he laughs.

He was well off the mark. These days you are never more than a few feet away from a lithium-ion battery, as they power mobile phones and all sorts of other electronics, from toothbrushes to electric scooters.

In recognition of that success, Prof Yoshino was awarded the 2019 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

But despite improvements, even the most advanced lithium-ion batteries can only store a fraction of the energy of a similar weight of petrol or jet fuel.

And that is curbing ambitions for even smaller and lighter devices - and more ambitious projects like electric powered aviation.

Solid progress

Batteries need to make progress, admits Prof Yoshino, but thankfully, "there's a lot of interesting approaches".

And "the solid state battery, I think, is a promising one," he says.

Solid state batteries can store 50% more energy than lithium-ion, says Douglas Campbell, chief executive of Solid Power, a Colorado university spin-off.

They are more stable as well. In lithium-ion batteries the gel inside, the electrolyte, can combust.

In 2016, Samsung recalled 2.5 million Galaxy Note 7 handsets after fires involving their lithium-ion batteries.

Lithium-ion batteries in the Galaxy Note 7 were prone to overheating

Solid state batteries replace that gel with less flammable solid polymers or ceramics.

But the batteries being developed by Mr Campbell's firm still require lithium in its metallic form and that's a problem because it is a hard metal to work with.

Another problem is that lithium metal isn't yet refined on an industrial scale, so just getting enough could be difficult, according to Mr Campbell.

But despite those worries, solid state batteries have "had the breakthrough in basic research, and research and development for mass production techniques is progressing," says Prof Yoshino.

He thinks it could take another 10 years for solid state batteries to compete with lithium-ion in terms of price.

Eyes on the prize

The big prize in the market is batteries for electric cars.

The number of electric vehicles in the world will balloon to 125 million by 2030, the International Energy Agency forecasts.

Battery innovation is "pretty much driven by whatever's happening in the electric vehicle market", says Rory McCarthy, an analyst at energy research firm Wood Mackenzie.

Mr McCarthy says the challenge for solid state and other new technologies is to compete with lithium-ion plants, which are getting bigger and bigger, making their batteries cheaper.

It takes a new battery factory four to five years to get close to full capacity and 10 years to make its money back, he adds.

Watts ahead

Lithium-ion technology itself is not a dead end. "We're learning some new principles we haven't thought of before," says Prof Yoshino.

That includes the movement of lithium-ions inside batteries. "We thought we understood that," he adds.

But now scientists are having to revisit their understanding, since it "is not what we expected".

"Yes, it goes on and on it never ends", he laughs.

Sila Nanotechnologies is working on improving lithium-ion batteries

Gene Berdichevsky says that it's only lithium-ion batteries that can make a "meaningful" impact on batteries in the near future and spur the mass adoption of electric vehicles.

His California-based company, Sila Nanotechnologies, is developing lithium-ion batteries that can potentially deliver a 40% improvement in energy density.

They are doing that by by replacing the graphite anodes (the part of the battery where the current flows in) with silicon.

"We need continued investment and innovation in lithium-ion batteries," he says.

Electric flight?

Eviation's nine-seater electric aircraft is among the pioneers of electric aviation

Better battery density could make big differences in the way we live.

Aeroplanes release 500 million tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere each year.

But with better batteries, aircraft can use cleaner power and that revolution is already underway.

This year's Paris air show saw a working all-electric prototype commercial aircraft, made by the Israeli start-up, Eviation.

US regional airline Cape Air has placed a double-digit order. Meanwhile Canada's Harbour Air said in March it aims to become the world's first all-electric airline.

With 30% of flights under 300 miles, short haul flight should be easy to electrify, says Los Angeles start-up Wright Electric.

And much denser batteries could also electrify big lorries that today rely on fossil fuels.

Curt Oswalt's wheelchair depends on batteries

Meanwhile, for some better batteries could change their lives.

"I have an off-road chair with six wheels," says Curt Oswalt, a former US air force translator who uses a battery-powered wheelchair after a 2002 injury.

"My batteries first started acting up roughly two years ago," he says.

One night, unable to sleep, he went for a 01:00 stroll around his neighbourhood in the Texan countryside.

"My battery indicator went from reading three-quarters full to dead, in under three seconds," he says.

Stranded, he had to wait under a street light until 04:30, when a sheriff found him and helped him home.

A more recent battery failure has meant he's been unable to leave his house unassisted for nine days.

"So yes," he says, "looking forward to better batteries!"