The £7,500 dress that does not exist

- Published

Mary Ren in the digital dress bought by her husband

Earlier this year Richard Ma, the chief executive of San Francisco-based security company Quantstamp, spent $9,500 (£7,500) on a dress for his wife.

That is a lot of money for a dress, particularly when it does not exist, at least not in a physical form.

Instead it was a digital dress, designed by fashion house The Fabricant, rendered on to an image of Richard's wife, Mary Ren, which can then be used on social media.

"It's definitely very expensive, but it's also like an investment," Mr Ma says.

He explains that he and his wife don't usually buy expensive clothing, but he wanted this piece because he thinks it has long-term value.

"In 10 years time everybody will be 'wearing' digital fashion. It's a unique memento. It's a sign of the times."

Ms Ren has shared the image on her personal Facebook page, and via WeChat, but opted not to post it on a more public platform.

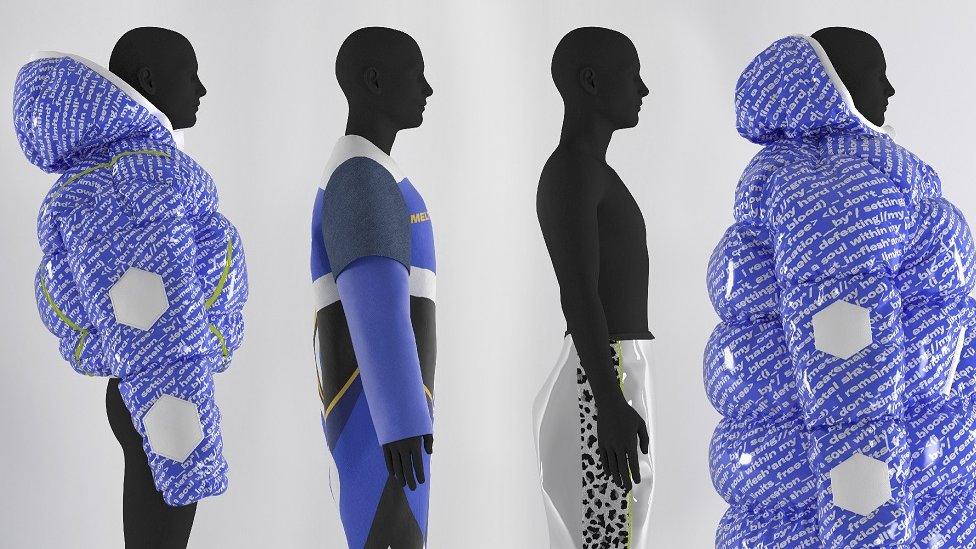

Carlings "sold out" its digital streetwear collections

Digital collection

Another fashion house designing for the digital space is Carlings. The Scandinavian company released a digital street wear collection, starting at around £9 ($11), last October.

It "sold out" within a month.

"It sounds kinda stupid to say we 'sold out', which is theoretically impossible when you work with a digital collection because you can create as many as you want," explains Ronny Mikalsen, Carlings' brand director.

"We had set a limit on the amount of products we were going to produce to make it a bit more special.

Being digital-only allows designers to create items that can push boundaries of extravagance or possibilities.

"You wouldn't buy a white t-shirt digitally, right? Because it makes no sense showing it off. So it has to be something that you really either want to show off, or an item that you wouldn't dare to buy physically, or you couldn't afford to buy physically."

Carlings can take risks with a digital only collection

Carlings' digital collection was produced as part of a marketing campaign for their real, physical products. But the firm thinks the concept has potential - a second line of digital garments is planned for late 2019.

The Fabricant releases new, free digital clothes on its website every month, but consumers need the skills, and software, to blend the items with their own pictures.

This also means the company has to find another way to make money until digital fashion becomes more popular.

"We make our money by servicing fashion brands and retailers with their marketing needs, selling tools, and creating content that uses that aesthetic language of digital fashion," says The Fabricant founder Kerry Murphy.

It is not entirely clear who is buying the digital garments from Carlings, or downloading clothes from The Fabricant.

Mr Mikalsen says Carlings has sold between 200-250 digital pieces, but a search to find them on Instagram only resulted in four people who independently purchased from the collection and had no involvement with the company.

However, some of the those clothes might have only been shared privately.

Some people want the perfect outfit for a particular location

Amber Jae Slooten, a co-founder and designer at The Fabricant, concedes it is mainly industry professionals, who use the CLO 3D software, that are downloading their clothes.

"But it's also just people are very curious to see what the files look like. People just want to own the thing, especially since that one dress sold for $9,500."

Marshal Cohen, chief retail analyst at market research company NPD Group, calls the emergence of digital fashion an "amazing phenomenon", but is yet to be convinced about its long-term impact.

"Do I believe it's going to be something huge and stay forever? No."

He says the technology works for people who want the perfect image. "If you don't like what you're wearing, but you love where you are, you now have the ability to transition your wardrobe, and digitally enhance the photograph to make it look like you're wearing the latest and greatest."

The digital fashion collections have been inspired by the outfits in games like Fortnite

Players of computer games have long been willing to spend money on outfits, or skins, for their in-game characters. That partly inspired The Fabricant to work in the digital space.

"The only reason we made the collection the way we did - inspired from Fortnite - was because of the whole link between buying skins and buying digital clothing," Mr Mikalsen says.

"When it comes to technology and the way people are living their lives, we have to be aware of that the world is changing."

Designers working on skins for games face extra challenges - they have to make sure it fits the story and the character.

Once the outfit is designed, which can take one try or 70, the hardest part starts according to in-games cosmetics consultant Janelle Jimenez.

The skins have to work in the game - a medium that, unlike digital fashion, often involves movements such as walking, fighting or dancing.

"For a game like League of Legends, you have to do 3D, there's sound effects, there's animations, all of these things have to come together to make the character feel like they're sort of expressing a different fantasy of themselves.

"It's less like changing clothes and more like seeing an actor playing a different role."

Buyers of digital fashion don't have to worry about taking something back if it doesn't fit

The influence of games and shifts in customer tastes gives some in the fashion industry confidence that digital clothes, in some capacity, will have long-term impact.

"Digital fashion will become an important part of every fashion business' future business model," says head of the Fashion Innovation Agency at the London College of Fashion, Matthew Drinkwater.

"It's not going to replace everything, but it will be an important part of that."