Boeing expects 737 Max to fly again by New Year

- Published

Boeing has said it expects its troubled 737 Max aircraft to return to the skies before the end of the year.

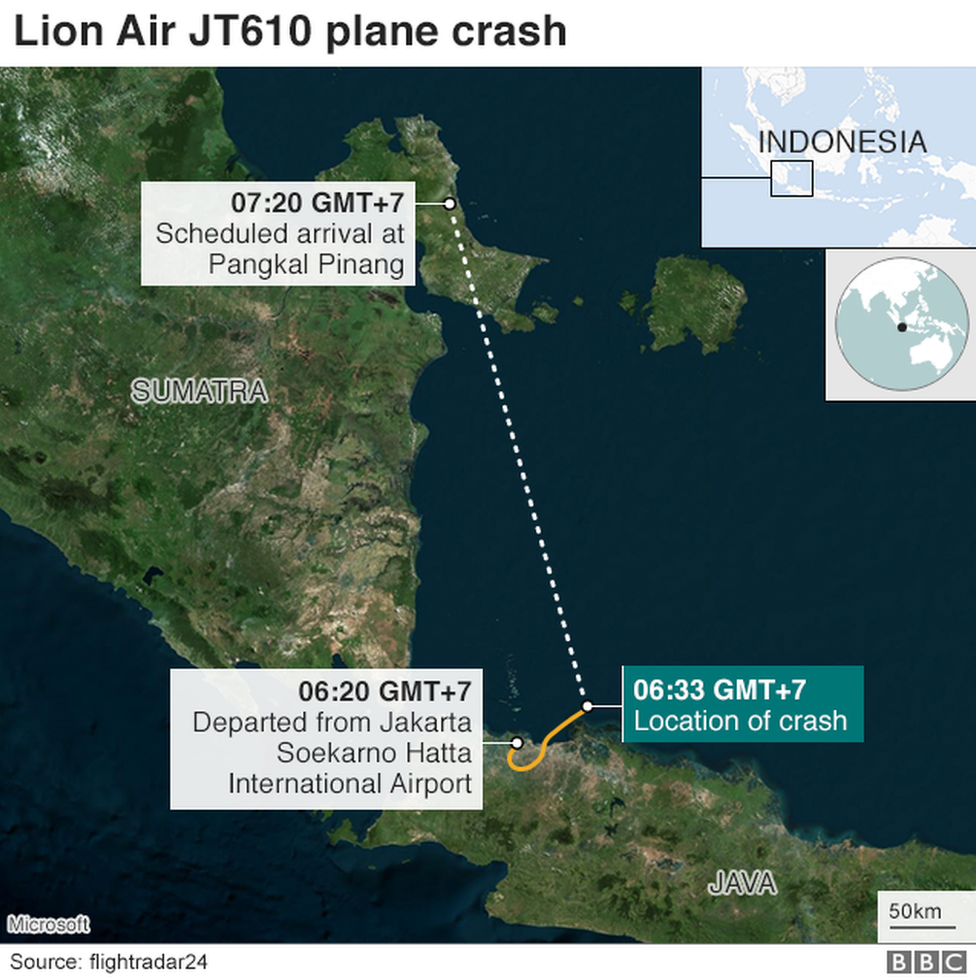

The jet was grounded after two fatal crashes, including last year's Lion Air disaster which killed 189 people.

Just hours after Indonesian investigators blamed mechanical and design problems for the crash, Boeing said it had developed software updates.

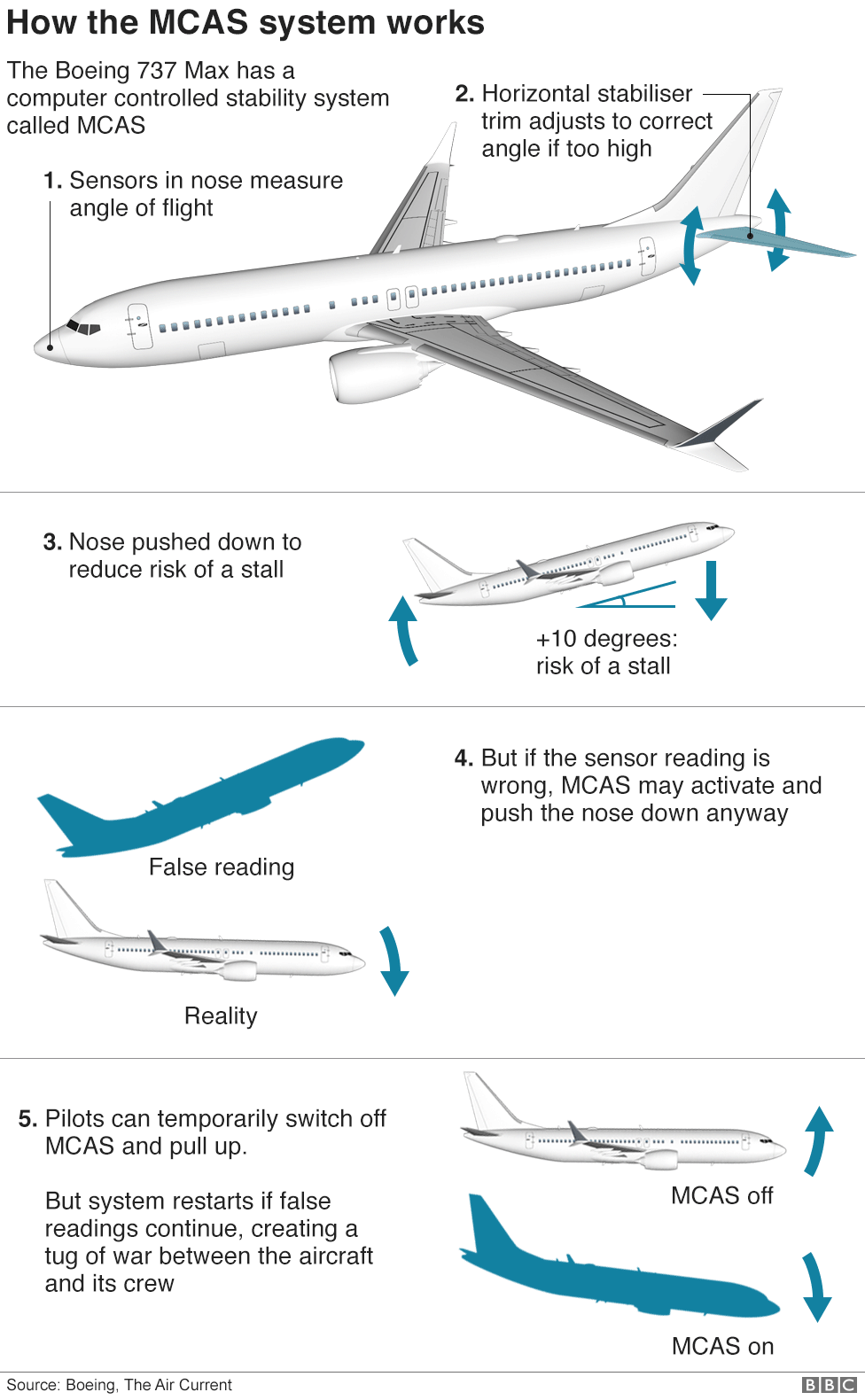

The investigators focused on a system used to improve handling and prevent stalling on the Boeing 737 Max.

Why did the Lion Air plane crash?

The official report by the Indonesian authorities into the disaster, which occurred 13 minutes after take-off from Jakarta on 29 October 2018, is expected to be published on Friday.

But on Wednesday, the authorities informed the victims' families of the findings.

Boeing did not comment ahead of formal publication of the report. But according to the information provided to the families, mechanical and design problems with the flight control system were among the causes of the crash.

The report highlighted issues with the MCAS (Manoeuvring Characteristics Augmentation System), which was designed to make the aircraft easier to fly.

What did it say about the MCAS?

Indonesia's National Transportation Safety Committee told families that MCAS would be a "contributing factor".

According to reports, families have been told that there were incorrect assumptions about how the MCAS control system would behave and that the "deficiencies" had been highlighted during training.

Slides from the briefing to the families showed that there was a lack of documentation about how a "stick shaker" - warning pilots of a loss of lift - would work.

Reuters reported that a "stick shaker" was warning of a stall throughout the 13 minutes the plane was in air, with investigators believing this was based on erroneous data on its angle to the oncoming air.

"During the design and certification of the [737 Max], assumptions were made about pilot response to malfunctions which, even though consistent with current industry guidelines, turned out to be incorrect," the report said, according to AFP.

The report found the system relied on a sole sensor for inputs and that a replaced sensor had been "miscalibrated" during an earlier repair.

When will the 737 Max fly again?

The planes were grounded after an Ethiopian Airlines crash in March 2019, which took the death toll to 346 people.

Boeing said on Wednesday it was working with regulators to return the jet to service.

"Our top priority remains the safe return to service of the 737 Max, and we're making steady progress," Boeing boss Dennis Muilenburg said.

The firm said it had also developed a training update and that it expected regulators to allow the planes to take off again before the beginning of 2020.

"We've also taken action to further sharpen our company's focus on product and services safety, and we continue to deliver on customer commitments and capture new opportunities, with our values of safety, quality and integrity always at the forefront," Mr Muilenburg said.

What has it meant for Boeing?

The grounding of the 737 Max hurt the planemaker's financial results in the third quarter.

Profits more than halved to $895m (£694m) and the firm said it would cut production of its 787 Dreamliner, blaming trade uncertainties.

Mr Muilenberg was stripped of his title as chairman by the board earlier this month, but remains as chief executive.

On Tuesday, Boeing ousted Kevin McAllister, chief executive of Boeing Commercial Airplanes, becoming the most senior official to leave since the two crashes.

When did Boeing know about the problem?

Mr Muilenburg is under pressure to explain what the company knew about issues with the 737 Max.

Questions about how much Boeing knew about problems with the 737 Max have been raised since Boeing provided documents to US lawmakers that showed employees had exchanged instant messages about issues with MCAS as it was being certified in 2016.

A pilot wrote that he had run into unexpected trouble during tests, saying he "basically lied to the regulators [unknowingly]".

The documents were provided ahead of Mr Muilenburg's appearance before Congress next week.

Why was not more drastic action taken?

The testimony from relatives of those on board Lion Air flight 610 raises yet more uncomfortable questions about the design of the 737 Max.

And the focus remains on the aircraft's new flight control system, known as MCAS, which erroneously pushed the plane into a nosedive.

The notion that assumptions made by Boeing and the regulators who signed the aircraft off about how that system would perform and how pilots would react to it were "incorrect" suggests something went badly wrong.

Every air crash is a chain of events and according to the families, the actions of the pilots were also a factor.

But the vulnerability of the MCAS system, which previously relied on data from one single sensor, is again in the spotlight.

The departure of Kevin McAllister, who ran Boeing's commercial planes division, speaks of the wider fallout.

The fundamental question belying everything is: why was more drastic action not taken after the Lion Air crash before a second accident killed another 157 people and grounded the plane worldwide?

- Published26 September 2019

- Published23 September 2019

- Published5 September 2019