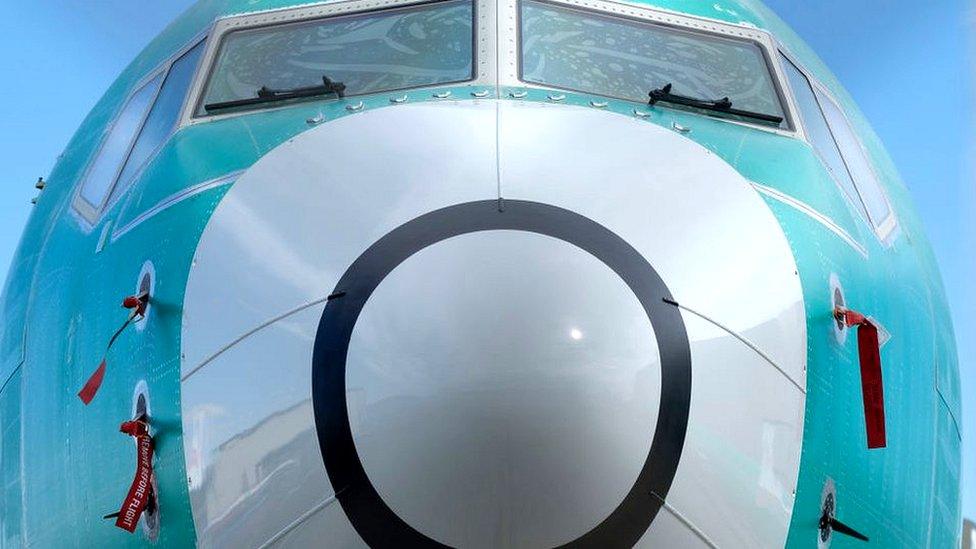

Boeing 737 Max Lion Air crash caused by series of failures

- Published

A series of failures led to the crash of a Lion Air flight, which killed 189 people and led to the grounding of the Boeing 737 Max, a report has found.

Investigators said faults by Boeing, Lion Air and pilots caused the crash.

Five months after the disaster in October last year, an Ethiopian Airlines plane crashed, killing all 157 people on board, which led to the grounding of the entire 737 Max fleet.

Faults with the plane's design have been linked to both crashes.

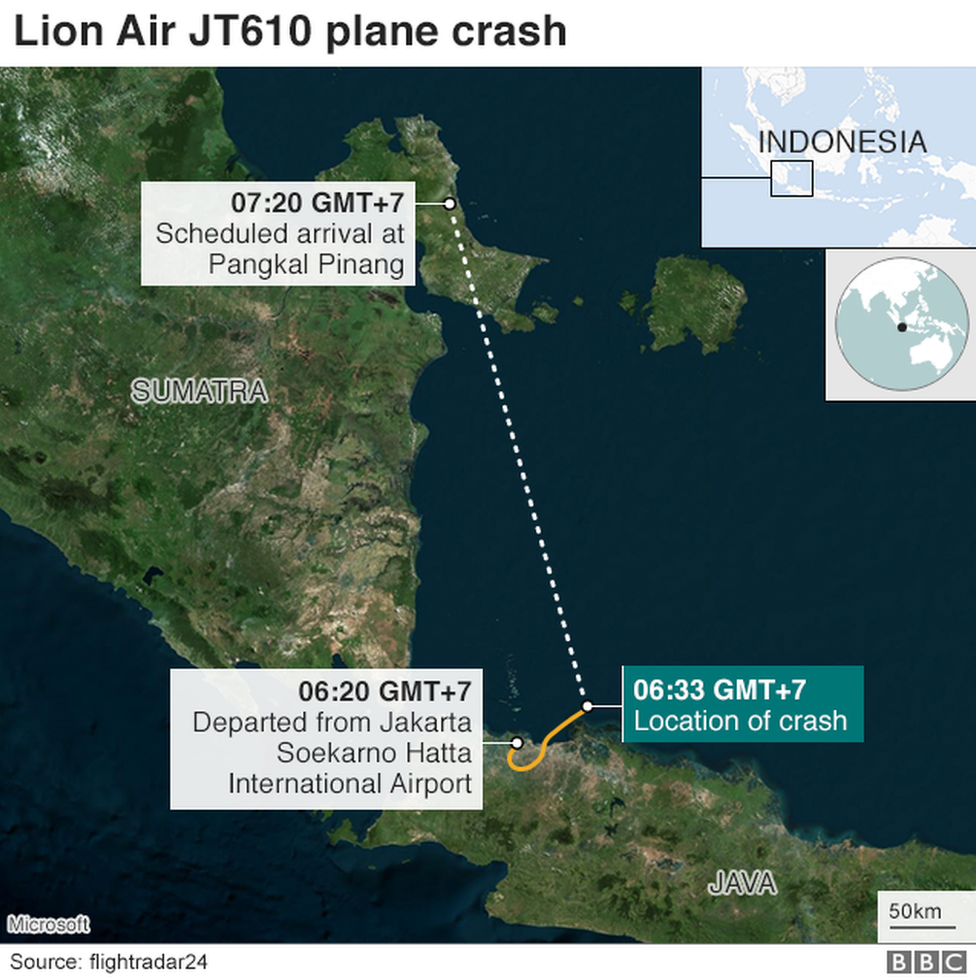

On Friday, air crash investigators in Indonesia released their final report, detailing the list of events that caused the Lion Air jet to plunge into the Java Sea.

"From what we know, there are nine things that contributed to this accident," Indonesian air accident investigator Nurcahyo Utomo told reporters at a news conference.

"If one of the nine hadn't occurred, maybe the accident wouldn't have occurred."

What does the report say?

The 353-page report found the jet should have been grounded before departing on the fatal flight because of an earlier cockpit issue.

However, because the issue was not recorded properly the plane was allowed to take off without the fault being fixed, it said.

Further, a crucial sensor - which had been bought from a repair shop in Florida - had not been properly tested, the report found. On Friday, the US aviation regulator revoked the company's certification.

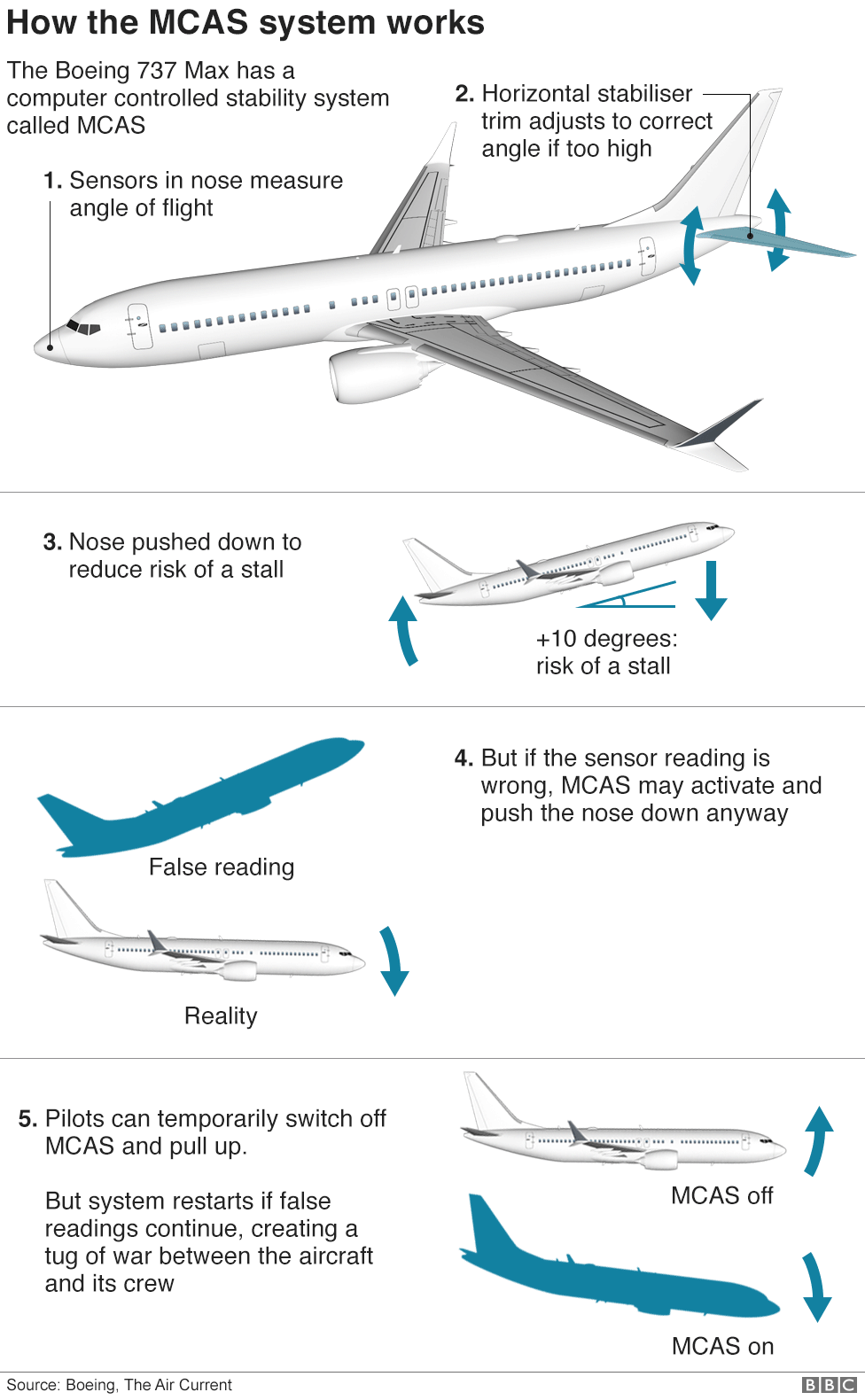

The sensor fed information to the plane's Manoeuvring Characteristics Augmentation System - or MCAS. That software, which is designed to help prevent the 737 Max from stalling, has been a focus for investigators trying to find the cause of both the Lion Air and Ethiopian Airlines crashes.

Indonesian investigators identified issues with the system, which repeatedly pushed the plane's nose down, leaving pilots fighting for control.

It showed there were incorrect assumptions about how the MCAS control system would behave and that the "deficiencies" had been highlighted during training.

Further, the report found that the first officer, who had performed poorly in training, struggled to run through a list of procedures that he should have had memorised.

He was flying the plane just before it entered into the fatal dive, but the report said the captain had not briefed him properly when he handed over the controls as they struggled to keep the plane in the air.

The report also found that 31 pages were missing from the plane's maintenance log.

Indonesian investigators have previously said mechanical and design problems were key factors in the crash of the Lion Air plane.

This report describes a catalogue of failures - from poor communication to bad design to inadequate flying skills - which culminated in the deaths of 189 people.

There are lots of what-ifs here. If the crew of the previous days flight had given a more detailed description of the problems they'd faced, the aircraft might never have taken off on its fatal flight. And if the captain, who'd successfully kept the plane in the air - despite the intervention of a rogue automated system he didn't understand - hadn't handed over to his less-capable first officer, disaster might still have been avoided.

As Boeing's chief executive Dennis Muilenburg has repeatedly stated, there was a chain of events. But at the heart of that chain was MCAS - a control system that the pilots didn't know about, and which was vulnerable to a single sensor failure.

Boeing - and regulators - allowed the system to be designed in this way and didn't change it after the Lion Air crash, leading to a further disaster. And that means that while the report clearly points to serious failures by a parts supplier and by the airline itself, it is Boeing that will bear the greatest share of responsibility.

How has Boeing responded?

Indonesian authorities laid out some recommendations for Boeing in the report, including that it redesign MCAS and provide adequate information about it in pilot manuals and training.

In a statement, Boeing said it was "addressing" the recommendations from Indonesia's National Transportation Safety Committee.

The planemaker said it was "taking actions to enhance the safety of the 737 Max to prevent the flight control conditions that occurred in this accident from ever happening again".

On Tuesday, the firm ousted Kevin McAllister, chief executive of Boeing Commercial Airplanes, making him the most senior official to leave the company since the two crashes.

Boeing also said it expected the 737 Max to be re-certified for flying by the end of the year. The company said "we look forward to continuing to work together" with Lion Air in the future.

A Lion Air spokesman said the crash was an "unthinkable tragedy" and it was essential to take immediate corrective actions to ensure a similar accident never occurred again.

'I lost my only son in the Lion Air plane crash'

What has been the fallout for Boeing?

The pressure on Boeing to explain what it knew about the problems with the 737 Max has intensified. There were revelations this month that employees had exchanged messages about issues with MCAS while the plane was being certified in 2016.

In documents provided by Boeing to lawmakers, a pilot wrote that he had run into unexpected trouble during tests. He said he had "basically lied to the regulators [unknowingly]".

Boeing said this week it had developed a training update and that it expected regulators to allow the planes to return to the skies before the beginning of 2020.

The grounding of the 737 Max has taken a toll on the planemaker.

Profits more than halved to $895m (£687m) in the third quarter and the firm said it would cut production of its 787 Dreamliner, blaming trade uncertainties.

Boeing boss Dennis Muilenburg was also stripped of his title as chairman by the board earlier this month, but remains as chief executive.

- Published25 October 2019

- Published23 October 2019

- Published28 November 2018

- Published18 October 2019