How much do we really know about why we give to charity?

- Published

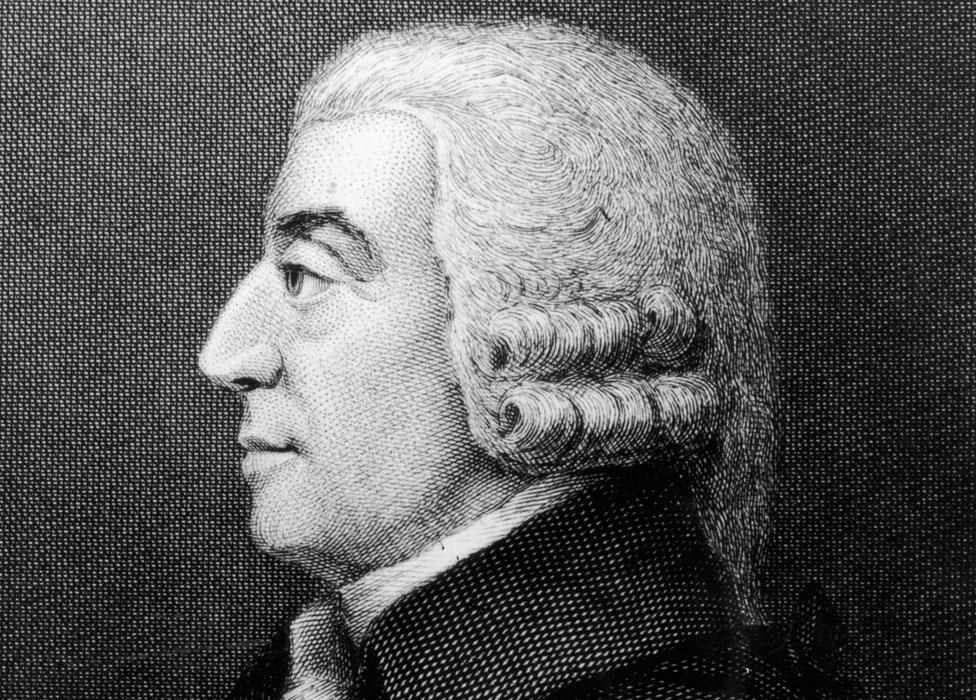

"It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves not to their humanity but to their self-love and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages."

When economist Adam Smith was writing his highly influential book The Wealth of Nations, external, in the 1770s, his mail probably didn't include envelopes with arresting images of hungry children.

And when he strolled around his home town of Kirkcaldy, Fife, he was not accosted by clipboard-wielding young women trying to sign him up for a monthly donation.

These days, we are frequently spoken to not of our advantages but of other people's necessities.

Charity has become big business, though it's hard to say how big: there's little good data.

One recent study estimates the British, for example, donate 54p in every £100, external. That's three times more than the Germans but three times less than Americans give.

By my reckoning, that's also roughly what Britons spend on beer, external, not much less than they spend on meat, external and three times what they spend on bread, external.

In economic significance, the charity fundraiser is up there with the butcher, brewer and baker.

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that helped create the economic world.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen to all the episodes online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

Charity, of course, is as old as humanity.

The ancient religious custom of tithing - indirectly giving a 10th of one's income to worthy causes - makes modern donations of less than £1 in every £100 seem derisory.

Still, taxes have replaced tithes and many modern fundraisers don't have the advantage of claiming to speak for God.

They need to be professional about persuasion - and there is a man who's regarded as the father of the field: Charles Sumner Ward.

In the late-19th Century, he started work for the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA).

He was "a medium-sized man," according to the New York Post, "so mild of manner that one would never suspect him of the power to sway hitherto reluctant pocketbooks".

That power first gained wide attention in 1905, when his employers sent him to Washington DC to raise money for a new building.

Ward found a wealthy donor to pledge a chunk of cash - but only if the public raised the rest. He then set an artificial deadline for this to happen. The papers lapped it up.

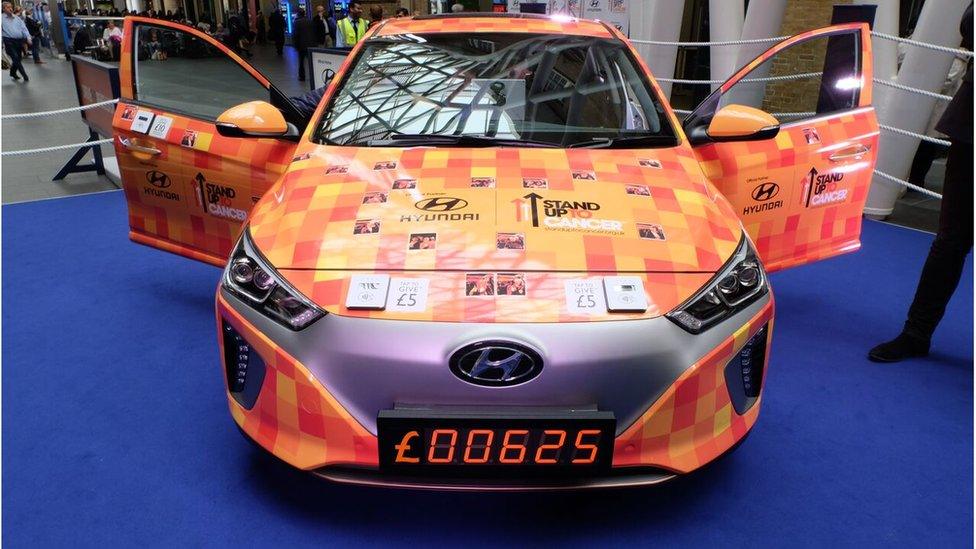

Ward used pioneering techniques, such as this fundraising clock for new YMCA buildings in New York, circa 1900

Ward applied his methods far and wide: a target; a time limit; a campaign clock, showing progress; publicity stunts planned with military precision.

In the modern world, they all seem familiar but when Ward came to London in 1912, they were novel.

The Times was suitably impressed by his "knowledge of human nature, and an extremely shrewd application of business principles in securing the advantage at the psychological moment".

World War One brought more fundraising innovations: lotteries; and flag days, which have modern equivalents in wristbands, ribbons and stickers that show you've given money.

Flags were often sold by society ladies, such as Lady Hanbury Williams and Mrs Schlater pictured on Soldier's Day in May 1917

By 1924, Ward had a fundraising company and was advertising how much it had raised for everything from boy scouts to masonic temples.

For the modern heirs of Charles Sumner Ward, what counts as a "shrewd application of business principles"?

We can get some clues from advertising executives interviewed for the Guardian newspaper, external. Images of starving children don't rack up many "likes" on social media, they say, build your brand instead, engage and entertain.

Economists have also studied what motivates donations. One theory is called "signalling", external: we donate in part to impress other people. That might explain the enduring popularity of wristbands, ribbons and stickers: they display not only the causes that matter to us but our generosity too.

Then there's the "warm glow" theory, which says we give in order to feel nice - or less guilty, at least.

Experimental investigations of these ideas have produced results that are - well, a little depressing. Economist John List and colleagues sent people to knock on doors; some asked for a donation, others sold lottery tickets for the same good cause. The lottery tickets raised a lot more; no surprise there.

But the researchers also found attractive young women who asked for donations fared much better - about as well as the lottery sellers. As the study drily acknowledges, external: "This result is largely driven by increased participation rates among households where a male answered the door."

That's evidence for the signalling theory of altruism - and you can see exactly what kind of pretty young lady these gentlemen were keen to signal to.

More things that made the modern economy:

Another economist, James Andreoni, studied the "warm glow" idea, external by asking what happened to private donations when a charity started getting a government subsidy?

If donors gave purely from an altruistic desire to ensure the charity could function, then the donations should move to another worthy cause when the subsidy arrives. But that doesn't happen, which suggests we aren't purely altruistic - we just get a warm glow from feeling that we are.

It's starting to sound like Adam Smith's logic applies to charity after all. "It is not from the benevolence of the donor that we expect a contribution," a fundraiser might say, "but from their regard to making themselves feel good or look good to others."

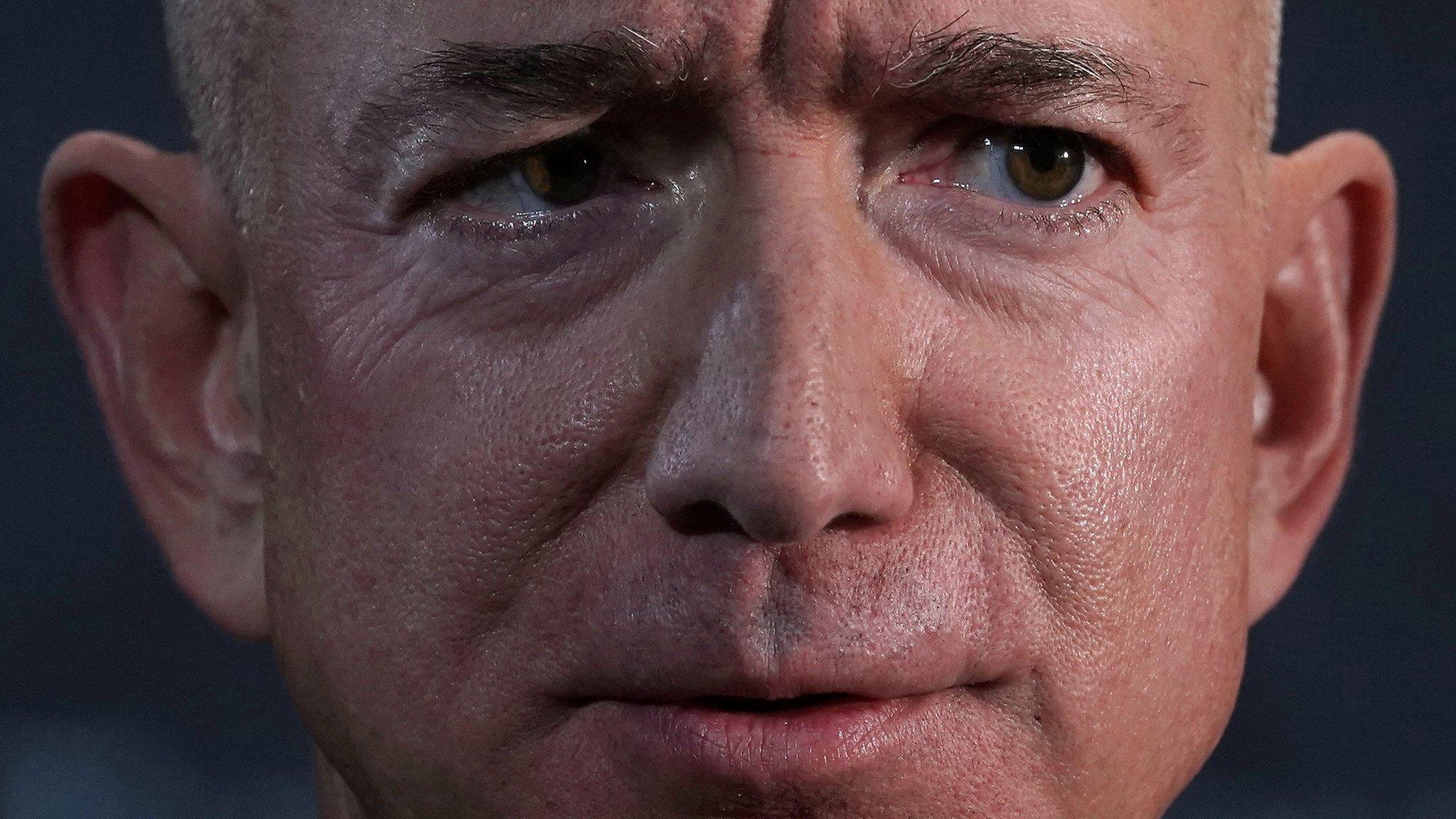

Formula One driver Daniel Ricciardo taking part in the Ice Bucket Challenge, which raised more than $115m (£87.7m) for research into progressive neurodegenerative disease ALS

But if charities are selling a warm glow and the ability to send social signals, that doesn't give them much incentive to do anything useful. They just have to tell us a good story.

Some people, of course, take very seriously the question of how much good charities do. There's a movement calling for "effective altruism", external, featuring organisations such as GiveWell, external, which studies charities' effectiveness and recommends who might deserve our cash.

The economists Dean Karlan and Daniel Wood wondered whether evidence of effectiveness would improve fundraising, and worked with a charity to find out.

Some supporters got a typical mailshot, an emotional story about an individual beneficiary called Sebastiana. "She's known nothing but abject poverty her entire life," it read.

Others got the same story but with an additional paragraph noting that "rigorous scientific methodologies" confirmed the charity's impact.

The results? Some people who'd previously given big donations seemed impressed and gave more. But that was cancelled out by small donors giving less. Merely mentioning science seemed to have punctured the emotional appeal and cooled the warm glow.

And this may explain why GiveWell hasn't even tried to assess the household names of the charity world - the likes of Oxfam, Save The Children, and World Vision.

In an exasperated-sounding blog post, external, the organisation explains such charities "tend to publish a great deal of web content aimed at fundraising but very little of interest for impact-oriented donors".

Or, as Adam Smith might have said: "Never talk to them of our own effectiveness".

The author writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen to all the episodes online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published2 April 2019

- Published1 January 2019

- Published16 September 2018

- Published23 February 2018

- Published21 August 2017

- Published9 June 2017

- Published18 August 2017

- Published27 July 2016