The Bezos backlash: Is 'big philanthropy' a charade?

- Published

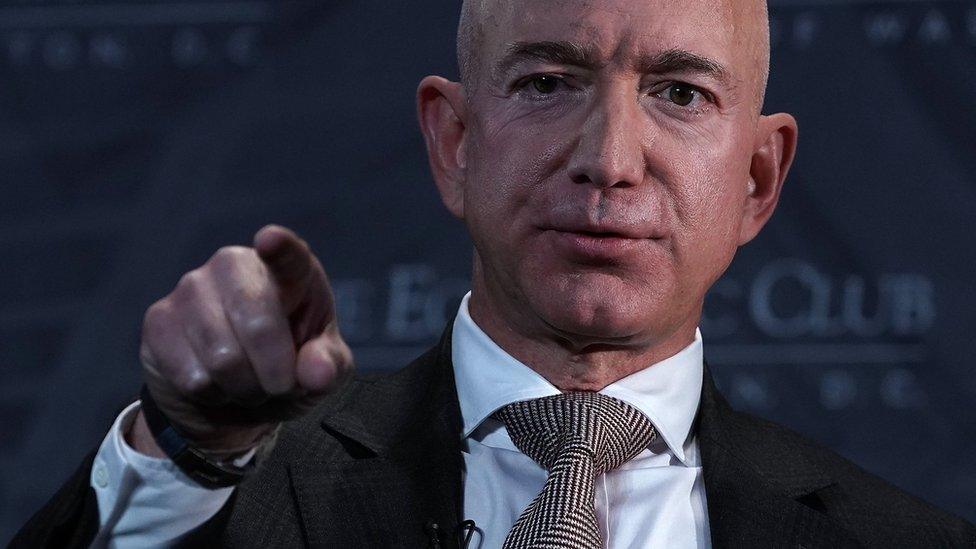

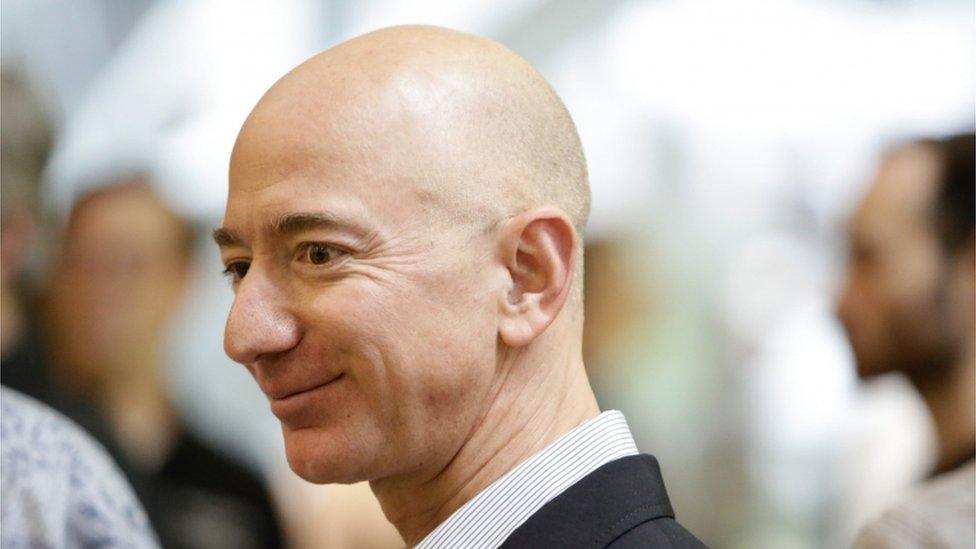

Amazon owner Jeff Bezos has been criticised by President Trump for paying "little or no taxes"

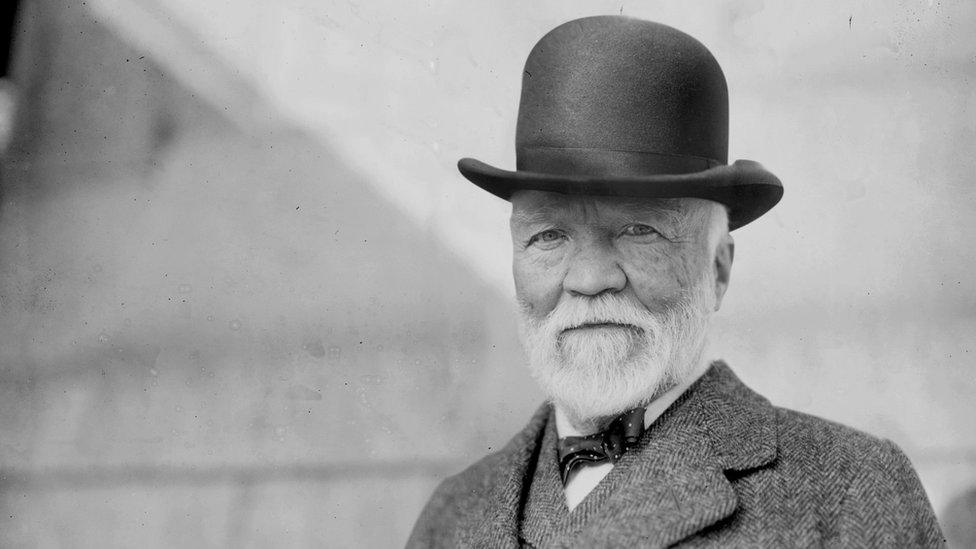

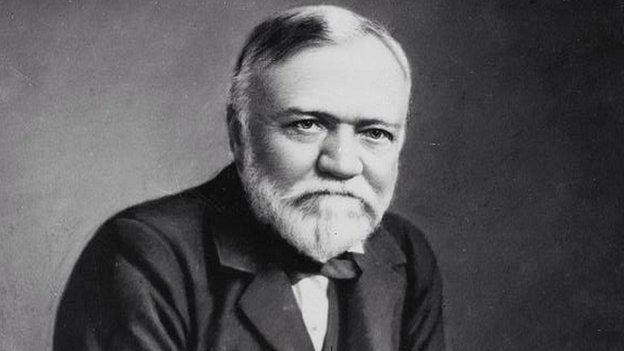

"Great fortunes," the American industrialist Andrew Carnegie is reported to have said, "are great blessings to a community."

No doubt the beneficiaries of multibillionaire Jeff Bezos's new philanthropic fund will agree.

The richest man in the world announced on Thursday that he would give $2bn (£1.5bn) of his fortune to finance a network of preschools and tackle homelessness in America.

But far from being universally applauded, the Amazon founder's pledge was met with fierce criticism.

James Bloodworth, a writer who went undercover to expose working conditions at the company's fulfilment centres, said there was "something slightly ironic" about Mr Bezos's plan.

"There have been credible reports of Amazon warehouse workers sleeping outside in tents because they can't afford to rent homes on the wages paid to them by the company," he told the BBC.

"Jeff Bezos can tout himself as a great philanthropist, yet it will not absolve him of responsibility if Amazon workers continue to be afraid to take toilet breaks and days off sick because they fear disciplinary action at work."

The treatment of Amazon's employees has been highlighted by several politicians, including Bernie Sanders

Accusations of hypocrisy flooded in on social media, with many pointing to Amazon's efforts to reduce its tax bill in the US and abroad.

Others highlighted Amazon's recent successful attempt to quash a law in Seattle, external - the home of the online retailer's headquarters - that was designed to raise millions of dollars to alleviate the city's homelessness crisis.

For his part, Mr Bezos, who is thought to be worth in excess of $150bn, did little to distance his philanthropic efforts from the business model of his company.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

"We'll use the same set of principles that have driven Amazon," he said in the statement announcing his fund.

"Most important among those will be genuine, intense customer obsession.

"The child will be the customer."

The Carnegie legacy

Yet the idea that business titans should apply the principles of their boardrooms to the public realm is hardly new.

It was first presented by Andrew Carnegie in 1899, in an essay entitled The Gospel of Wealth.

Andrew Carnegie is estimated to have parted with 90% of his fortune

The magnate - himself once the world's richest man - outlined what he saw as the moral duty of the super rich: "To consider all surplus revenues which come to him simply as trust funds, which he is called upon to administer."

Businessmen, Mr Carnegie argued, were best placed to do said administering.

"The man of wealth thus becoming the sole agent and trustee for his poorer brethren," he wrote, "bringing to their service his superior wisdom, experience, and ability to administer - doing for them better than they would or could do for themselves."

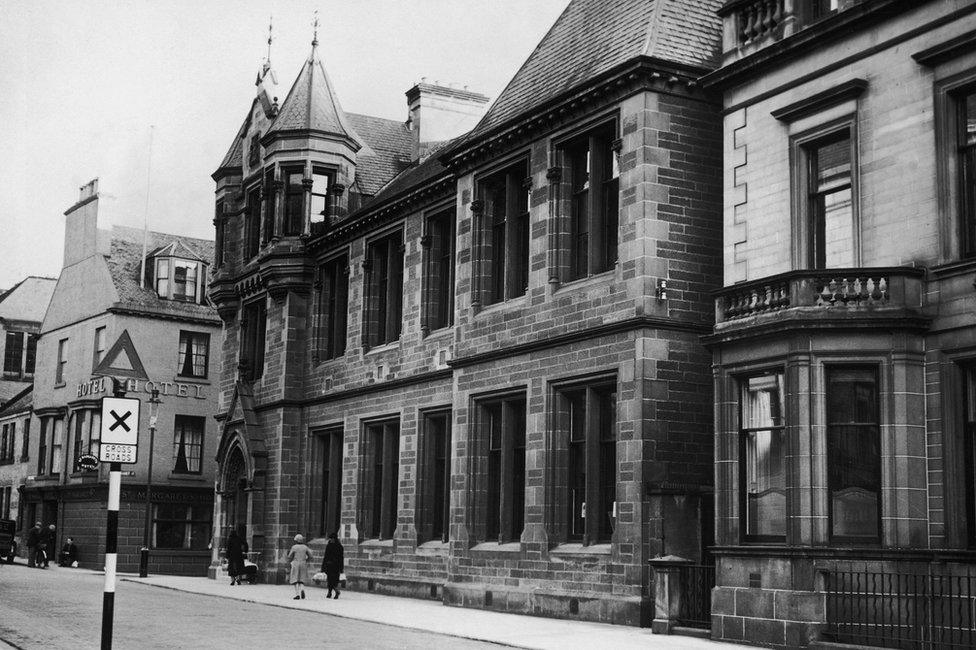

By the time he died in 1919, Mr Carnegie was estimated to have parted with 90% of his fortune, using it to fund scientific research, pay teachers, build schools and establish more than 2,000 public libraries.

The first Carnegie Library, in Dunfermline, Scotland

His doctrine became the model for donations by fellow tycoons, including John D Rockefeller, who saw no conflict between their approach to business - in which they built monopolies and crushed labour unions - and their philanthropic work.

It is a model that laid the path for the modern-day benefactions of Bill Gates, Warren Buffett and Mark Zuckerberg - whose charitable causes are distinct from the way they run their companies.

At this year's annual meeting of his firm Berkshire Hathaway, Mr Buffett could not have been clearer.

"I do not believe in imposing my political opinions on the activities of our businesses," he told assembled shareholders, when quizzed on whether he would divest from gun manufacturers.

Warren Buffett has drawn a line between his business practices and his politics

'Don't put a Band-Aid on cancer'

But according to Anand Giridharadas, Mr Carnegie's approach helped give rise to mass inequality.

Mr Giridharadas, whose book Winners Take All tackles the so-called "charade" of modern philanthropy, characterises Carnegie's approach as "extreme taking followed by extreme giving".

The super rich, he argues, stop short of "transforming the system atop which they stand".

While Mr Bezos's donation is admirable, he says, it does not tackle the "deep and complex root causes" of homelessness and poverty in the US - which include Amazon itself, as the firm has been a beneficiary of the new world of precarious employment.

A good motto for the likes of Mr Bezos, he suggests, would be: "Ask not what you can do for your country, ask what you have already done to your country."

Basketball star LeBron James recently announced he was setting up a school, and would pay graduates' college tuition

The approaches taken by the super rich, says Mr Giridharadas, are less bold than the companies they helped create.

"If you want to wade into public policy, you have a moral responsibility not to put a Band-Aid on cancer," he says, adding that Mr Bezos could work to influence policy instead.

One way in which he could do so is by fighting for a change in the law when it comes to companies' responsibilities to shareholders, and the bottom line - paving the way for corporate structures which sacrifice some profits in pursuit of social good.

Seattle, the home of Amazon's HQ, has seen a rise in homelessness

Matt Kilcoyne, of the free market think-tank the Adam Smith Institute, disagrees.

"Quite frankly Bezos's greatest act of philanthropy is Amazon itself," he argues.

"Lower prices, more choice and competition have delivered billions for Bezos and billions worth for the hundreds of millions of customers he serves."

What's more, Mr Kilcoyne dismisses any talk of the super rich's moral responsibility to give in a certain way.

"Jeff Bezos has a right to spend his own money as he pleases.

"Armchair commentators might like to say that they know better than Bezos what he should spend his money on, but they'd do better to try and convince him of their philanthropic cause than chastise him for his choice."

- Published13 September 2018

- Published4 December 2015

- Published15 October 2012

- Published17 September 2012

- Published2 September 2012