Giant jet engines aim to make our flying greener

- Published

The Ultrafan engine has giant carbon composite blades tipped with titanium

"It's on another scale from anything I've seen before," says Lorna Carter who recently started working at a new Rolls-Royce research and development facility near Bristol.

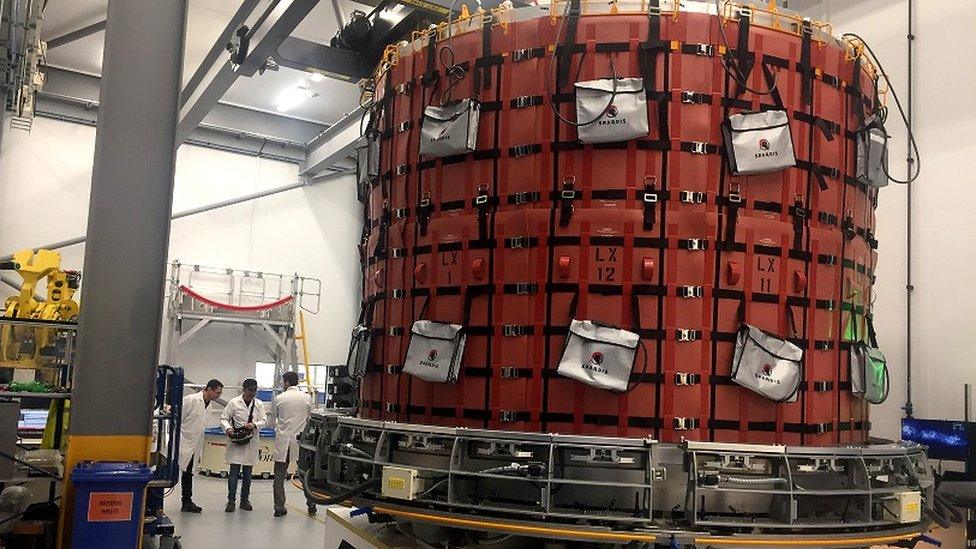

She works with giant robots which lay thousands of strips of carbon fibre tape to form a cylinder some 3.7m (almost 12ft) in diameter.

The cylinder forms the outer shell of Rolls-Royce's new engine, the Ultrafan.

Still under development, Rolls-Royce says the Ultrafan will be quieter and more fuel efficient than anything it has made before.

It will certainly be bigger.

"The component we're trying to make is massive and we are at capacity, it's really stretching the limits of what we can do," says Ms Carter.

At the £25m facility Rolls-Royce has also developed robots that can make fan blades from carbon fibre, a process that has taken more than 10 years to perfect.

Lorna Carter works with robots to build engine casings

Making the fan casing and blades from carbon fibre should result in a 20% weight saving compared with previous materials.

And that's important as the aerospace industry is under pressure to reduce its environmental impact. Aircraft are getting more efficient, but airline traffic is growing even faster.

Rolls-Royce estimates that 37,000 new passenger aircraft will be needed over the next 20 years.

"We've come a long way, but the challenge is to decouple emissions growth from traffic growth," says Alan Newby, future programmes director at Rolls-Royce.

The new engine will also incorporate a gearbox, allowing a much bigger fan, which results in a more efficient engine.

It's an innovation already being used on a smaller engine from US-based Pratt & Whitney Engine, the PW1000G.

While Rolls-Royce and others in the aerospace industry are working on electric and hybrid propulsion systems for aircraft, for long-haul aircraft, at the moment jet engines are the only option.

The giant new Rolls-Royce engine needs a fan case 3.7m wide

Given that it is a technology that has been around since World War Two, how much more efficiency can be squeezed out of the jet engine?

Quite a lot, according to Professor Pericles Pilidis, who is head of power and propulsion department at Cranfield University's Centre for Propulsion Engineering.

His department works with on research projects with aerospace companies including Airbus and Rolls-Royce.

"I do expect improvements to continue," he says. Better materials, more efficient shapes and improved coatings can all contribute to make engines lighter and stronger.

He also points out that lighter engines mean the aircraft structure can be lighter as it has to carry less weight.

Those kind of incremental changes might not sound like much, but in the airline business they can make a big difference.

"Evolutionary changes, they sound unimpressive - 10% here 12% there. But in the airline business with very thin margins, that is the difference between life and death," says Richard Aboulafia, vice-president of analysis at the Teal Group.

One UK firm though is looking to make a step change in propulsion. Reaction Engines is developing a rocket engine, called Sabre, to be used on high-speed aircraft and on spacecraft.

At the kind of speeds Reaction is aiming for, Mach 5 (five times the speed of sound) the air coming into the engine can reach temperatures of 1,000C.

Reaction Engines hopes its engines will allow travel at over five times the speed of sound

That temperature would destroy the engine, so Reaction has developed a cooling system which can chill the incoming air in a fraction of a second.

The so-called pre-cooler is made from miniature tubes, less than 1mm thick, that can pipe coolant under high pressure through the system, and whisk heat away.

"The Sabre is completely unique, there's nobody else in the world, that we are aware of, that's developing an air-breathing rocket engine," says Mark Thomas, chief executive of Reaction Engines.

"Our pre-cooler technology... is in a different class to anything out there. It's ultra-high performance, ultra lightweight, highly miniaturised... it's just in a different league completely."

Reaction Engines plans to start building the Sabre engine this year and test it in 2021.

Reaction's pre-cooler can also potentially be used on conventional jet engines to make them more efficient, an idea being tested with Rolls-Royce.

According to Prof Pericles it will be another 30 years until we see a radical change in passenger aircraft.

By then he thinks there will be a transition from the current design, which is basically a tube, with engines hanging below the wings, to a "blended wing" design.

In 30 years time aircraft might look more like this design from Cranfield University

Under that design, the aircraft is just one set of wings, with engines sitting on the top.

Those engines might even by powered by hydrogen, which has the potential to be a very low emission fuel.

"Hydrogen fuel is unavoidable," says Prof Pilidis. "It is a long-term solution to decarbonise aviation completely.

However, environmentalists says action needs to be taken sooner.

"There's always a role for technology to play in cutting emissions, but solving the climate crisis is something we need to get on with right now," says Jenny Bates, a campaigner at Friends of the Earth.

"The priority instead needs to be emissions cuts by having fewer planes in the sky. This is a crucial part of preventing further climate breakdown."

Follow Technology of Business editor Ben Morris on Twitter, external

More BBC coverage on climate change at Our Planet Matters