What will happen to oil if there is another war?

- Published

Mitch Kahn remembers how, when fighting began in the second war in Iraq, prices for US crude oil spiked $10 per barrel overnight.

That would have meant a profit of $50,000 if a trader had made the smallest purchasing trade possible. Or, just as big a loss if the trader had decided to sell.

Mr Kahn was working as an independent trader on the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) on Vesey Street in downtown Manhattan, where crude oil, gas and heating oil were traded downstairs and precious metals were traded upstairs.

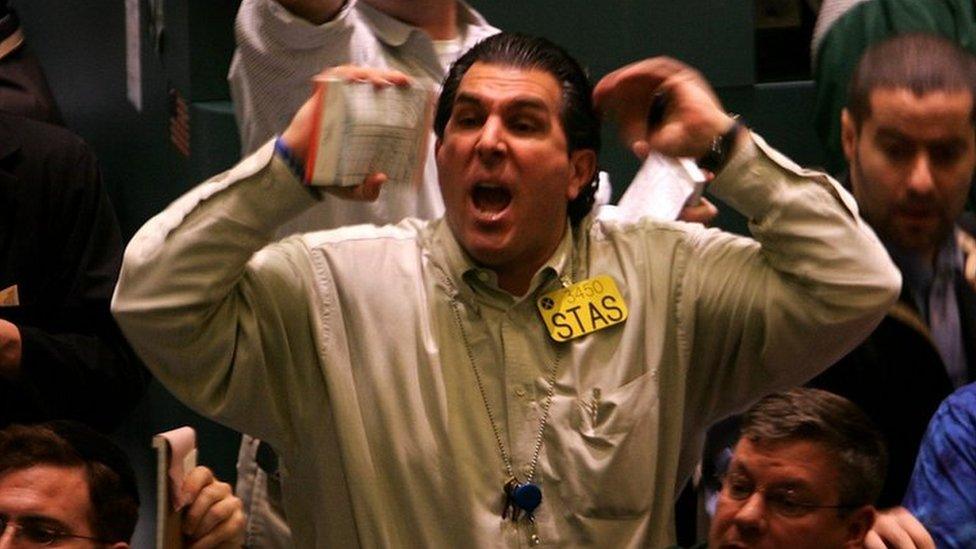

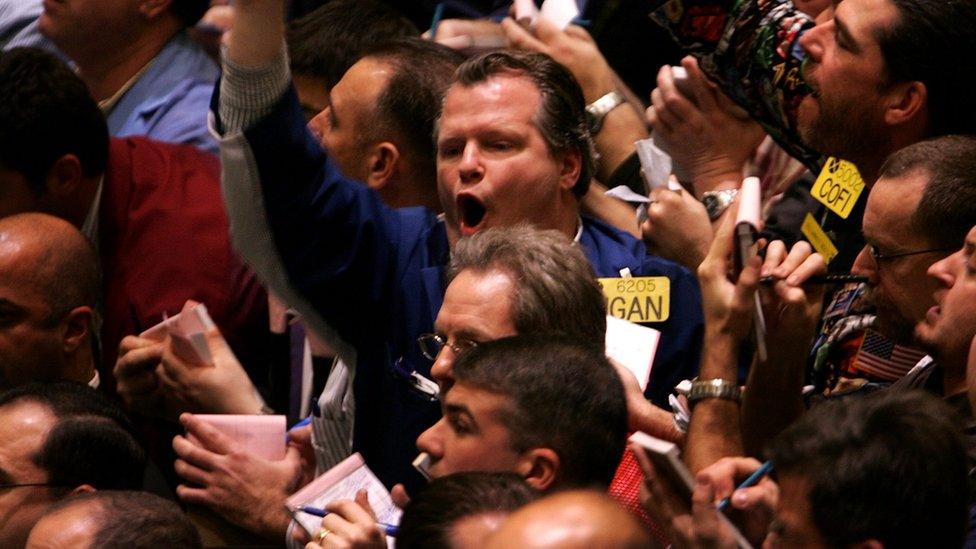

In 2004, when the second war in Iraq broke out, prices were decided by open outcry: the shouts and yells of (mostly) men who stood in a ring. Some bought, some sold, the price settled between what sellers and buyers were offering.

The ring got so loud that several traders wore earplugs, Mr Kahn says. But for him, the adrenaline was enough to keep his hearing clear.

While trading today is 24 hours, in 2004, when the bell buzzed at 14:30 EST, the market shut.

Oil traders on the floor of the New York Mercantile Exchange

That day in 2004, when the market opened, the trader on his right began to shout.

He remembers the trader next to him trying to sell some oil, "and the market collapsed."

Within minutes, a barrel of oil was $20 cheaper. But that is less likely to happen today.

"Markets move differently now," he says.

In fact, Mr Kahn points out, despite Friday's price spike, everything about the oil markets are different today than the last time war started in Iraq.

Places it is produced, the way it is refined and how it is traded bear no resemblance to oil he was working with when his adrenaline carried him through screaming price moves of the past.

The rules have changed

The price of Brent crude vaulted more than 4% to hit $69.50 a barrel on Friday.

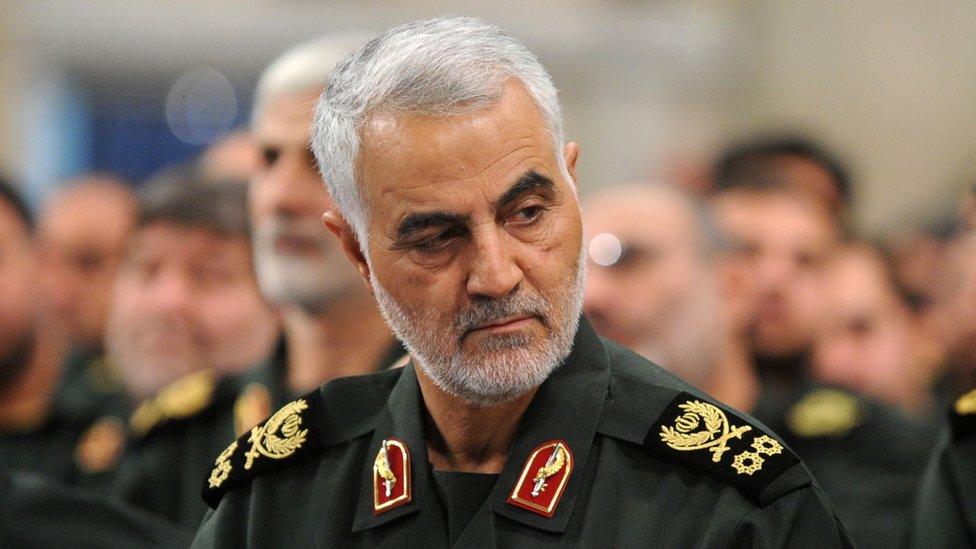

Oil prices swung on news that Iranian General Qasem Soleimani was killed in a US drone strike at Baghdad airport, which the Pentagon described as "defensive action".

Stock prices of BP and Royal Dutch Shell both rose around the 1.5%.

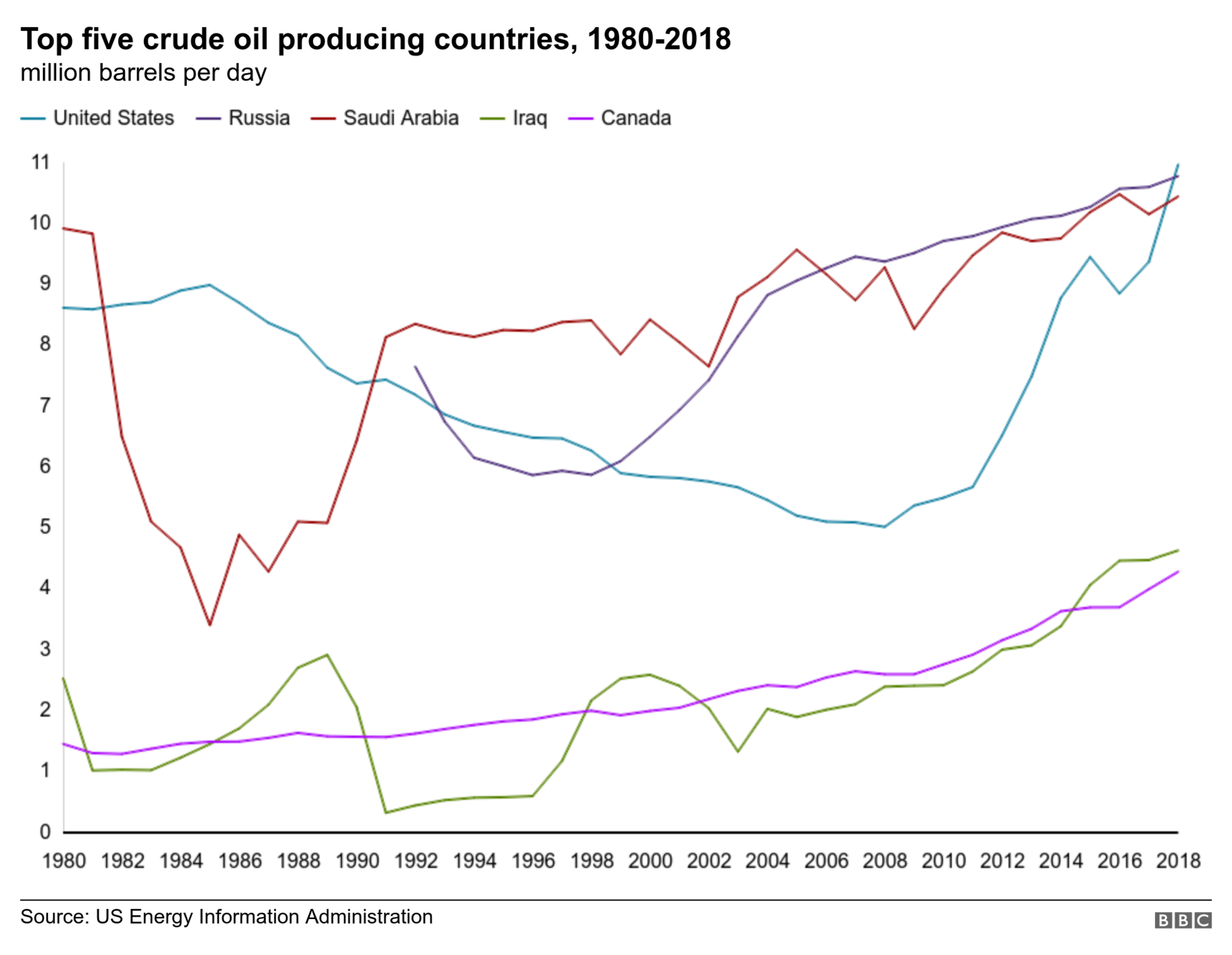

The single biggest factor that changes the game in oil from 2004 to now, says Michael Widmer, a commodities strategist at Bank of America, is that the US makes enough oil to be independent.

The US is no longer reliant on crude from the Middle East.

"The rules have changed materially," says Mr Widmer.

The drone attacks on the Saudi Arabian oil plants in September serve as a good example.

The attacks temporarily knocked out half of Saudi Arabia's crude oil production

"This is one of the biggest ever hits to the global oil market, in terms of supply and it had no sustained impact," he says.

That day the market surged almost $10 a barrel, but not much happened in the aftermath.

While tensions rose on the political scene with terse rhetoric flying between Iran and the US and a plan to deploy new sanctions, oil slid back down to below $60 a barrel a fortnight later.

But the sour political discourse outlasted any fears of price disruption.

That is because more countries, notably Russia and the US, are pumping out oil now.

Opec, the cartel of mainly middle eastern countries which used to control much of the supply of oil, no longer holds the same sway.

"Now when Opec cuts its production numbers, it just makes more breathing space for other countries to increase theirs," says Mr Widmer.

Alan Gelder, vice president of chemicals and oil markets at Wood Mackenzie, says one way to look at it is that Opec used to produce half the world's oil, but now makes less than a third of it.

In the Gulf War, which began in 1990, oil came from two places. Either it was made by Opec, or it was produced in places considered expensive and risky, like the North Sea.

Finding oil and getting it out of the ground from the ocean, especially 40 years ago, was an unpredictable and dangerous affair.

Now, because of the fracking done in North America, there is a glut of oil.

"Back then, commodity markets were just getting established. There are lots more participants in the market now," says Mr Gelder.

And far more information is available today than it was five years ago, he adds.

When Saudi Arabian producers were attacked last September, satellite imagery of ships leaving port and the plants themselves, showed that production restarted quickly and exports had resumed.

"Years ago, people would be frantically calling one another, trying to figure out what was going on," he says.

At the moment Opec and other oil producing companies like Russia have agreed to hold back on pumping out as much oil as they can.

That makes it particularly difficult to know what will happen to the price of oil as tensions rise in the Middle East.

In the short term, analysts at Citibank expect prices to stay high on retaliation fears.

Attacks on US oil company pipelines, or where Western and American oil companies have invested in new exploration, would drive crude higher.

Any resolution of the conflict between Iran and the US will de-escalate the situation and prices will deflate, they say.

- Published3 January 2020

- Published3 January 2020