Jeff Bezos hack: Saudi Arabia calls claim ‘absurd’

- Published

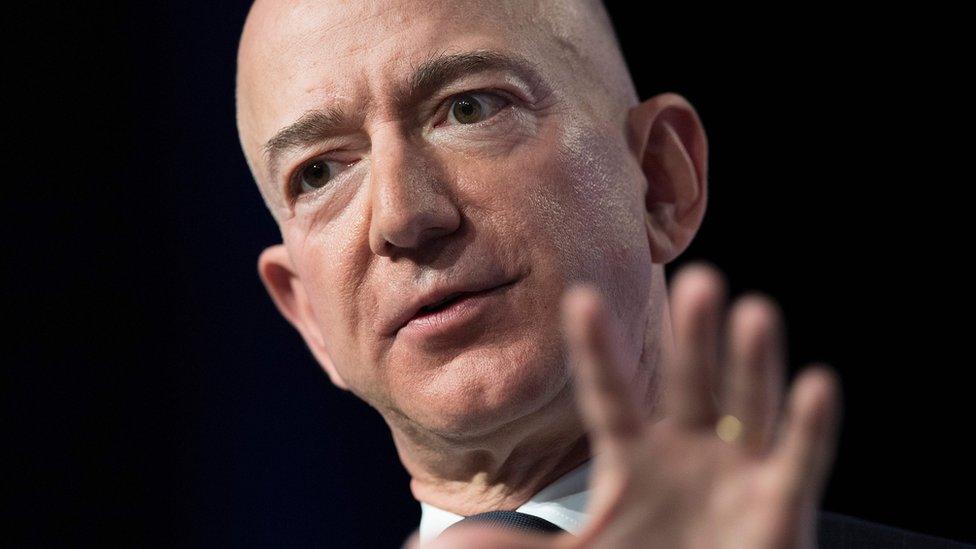

The relationship between Jeff Bezos and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman soured after Jamal Khashoggi's murder

Saudi Arabia has denied that its crown prince was responsible for hacking Amazon boss Jeff Bezos' phone.

A message from a phone number used by the prince has been implicated in the data breach, according to reports.

The kingdom's US embassy said the stories were "absurd" and called for an investigation into them.

Relations between Saudi Arabia and Mr Bezos - who owns the Washington Post - worsened after one of the newspaper's staff was killed in a Saudi consulate.

Jamal Khashoggi, a prominent critic of the Saudi government, was murdered in Istanbul months after this alleged cyber-attack took place.

In a blog post last year, Mr Bezos insinuated that the Saudi regime was unhappy with the "the Post's essential and unrelenting coverage" of the killing. "It is undoubtedly unpopular in certain circles," he wrote.

Mr Bezos' phone was hacked after receiving a WhatsApp message in May 2018 that was sent from Mohammed bin Salman's personal account, according to the Guardian newspaper, external which broke the story.

An investigation into the data breach reportedly found that the billionaire's phone had started secretly sharing huge amounts of data after he received an encrypted video file from the prince.

The Twitter account of the kingdom's US embassy , externalissued an outright denial of the claims.

Mohammed bin Salman is asked: "Did you order the murder of Jamal Khashoggi?"

Amazon did not immediately respond to a request for comment from the BBC.

The allegations are based on a report that was commissioned by the private security firm FTI Consulting, which was hired by Mr Bezos.

Two UN officials are expected to make a statement about the credibility of the allegations later on Wednesday.

Hacking 'horribly easy to do'

Analysis by Jane Wakefield, BBC News technology reporter

While the details of how this happened aren't yet public, evidence is pointing towards a WhatsApp conversation between the two men during which an infected video file was allegedly sent.

It is unclear what the content of that video was, but there is huge interest in finding out what a crown prince might send to one of the world's most powerful tech leaders.

Such a hack is "horribly easy to do once the vulnerability involved had been discovered," says cyber-security expert Prof Alan Woodward. The seemingly innocent video would have contained malware that surreptitiously installed itself on the targeted phone.

From there it would have been possible for the hacker to gain access to all the functions of the phone, from the GPS locator, to the camera, to the banking facilities and messaging apps.

Such access is made possible via bugs in the code and, last year, a security flaw in WhatsApp was revealed that would have allowed hackers to hide malicious code inside video files.

Phone hacking is, says Prof Woodward, all too common in certain countries that are keen to keep an eye on journalists, dissidents and other activists perceived to be a threat to their regimes. So-called stalkerware is available off the shelf to these governments.

But what about the involvement of the Saudi crown prince? Was it really him who installed the malware?

It is unlikely that he set the phone up himself. So was his phone also being spied on? Or was he simply a vessel being used by the Saudi authorities?

The plot thickens.

The reports come after private information about Mr Bezos was leaked to the American tabloid the National Enquirer.

In February 2019 Mr Bezos accused the National Enquirer of "extortion and blackmail" after it published text messages between him and his girlfriend, former Fox television presenter Lauren Sánchez.

A month earlier he and MacKenzie Bezos, his wife of 25 years, had announced that they planned to divorce having been separated for a "long period".

An investigator for the Amazon founder later said Saudi Arabia was behind the National Enquirer leak and had accessed his data.

"Our investigators and several experts concluded with high confidence that the Saudis had access to Bezos' phone, and gained private information," Gavin de Becker wrote on the Daily Beast website at the time.

Mr de Becker linked the hack to the Washington Post's coverage of the murder of Saudi writer Jamal Khashoggi at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul.

- Published16 February 2019

- Published31 March 2019

- Published24 February 2021