Rise in full-time female workers boosts employment

- Published

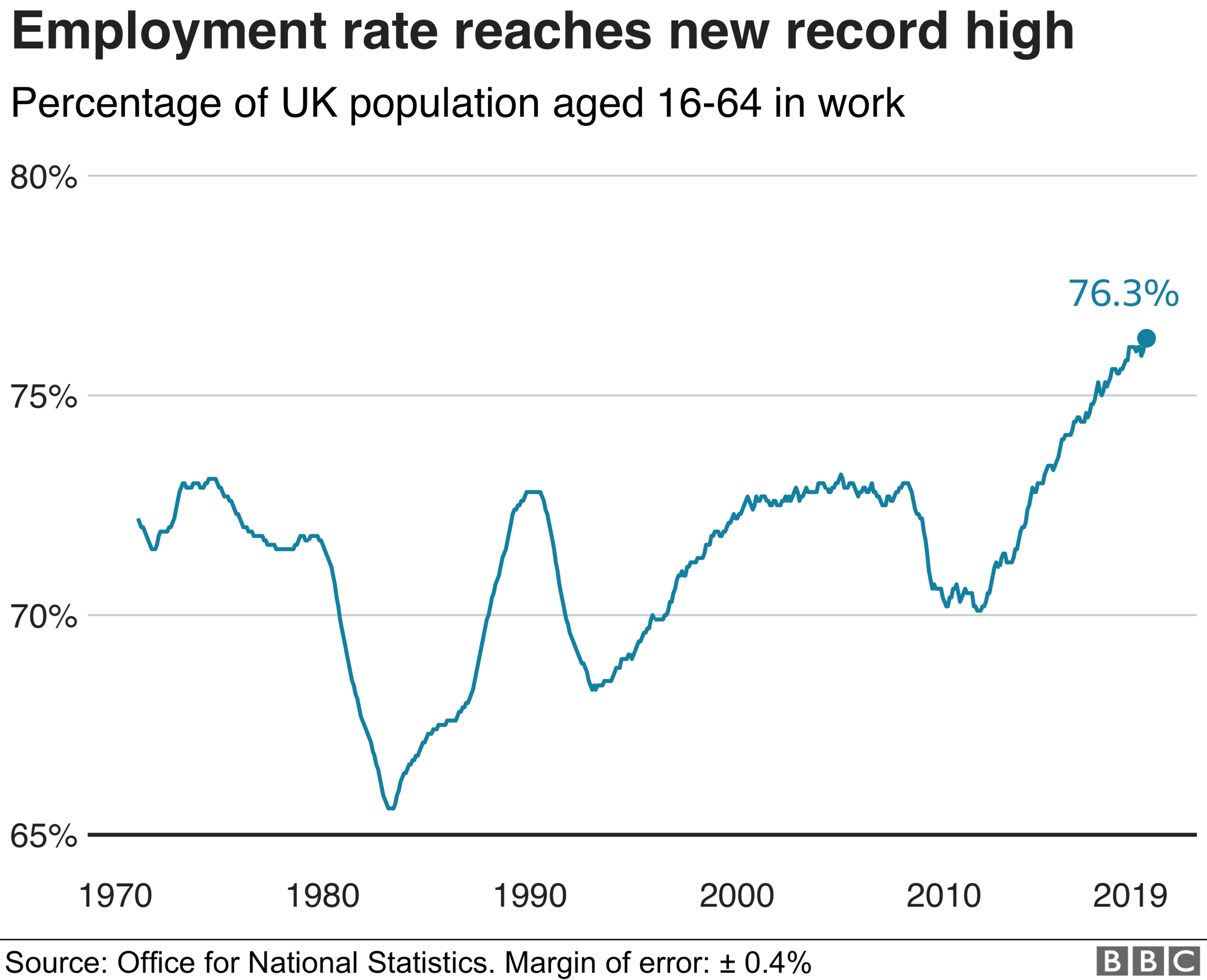

A record number of women in full-time work has pushed the UK's employment rate to a new high of 76.3%, the latest figures from the Office for National Statistics show., external

In the three months to November, 126,000 more women worked full-time compared with the previous quarter.

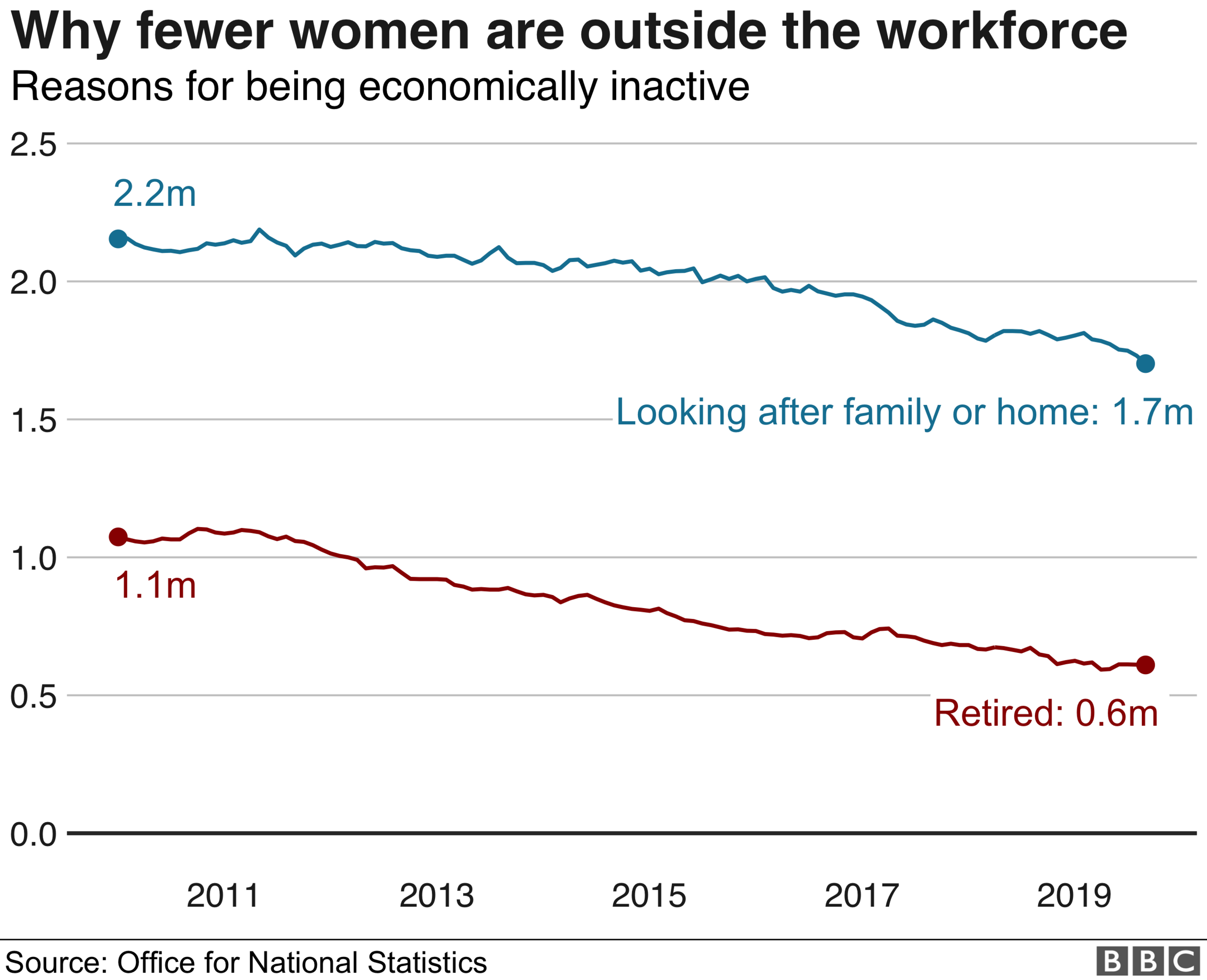

The increase is in part because of the change in women's retirement age.

The data may affect the Bank of England's decision over whether to cut interest rates next week.

A record 32.9 million people are in employment in the UK, a rise of 0.5% for the three months to November.

"The employment rate is at a new record high, with over two-thirds of the growth in people in work in the last year coming from women working full-time," said ONS head of labour market and households, David Freeman.

"Self-employment has also been growing strongly, and the number of people working for themselves has now passed five million for the first time ever," he said.

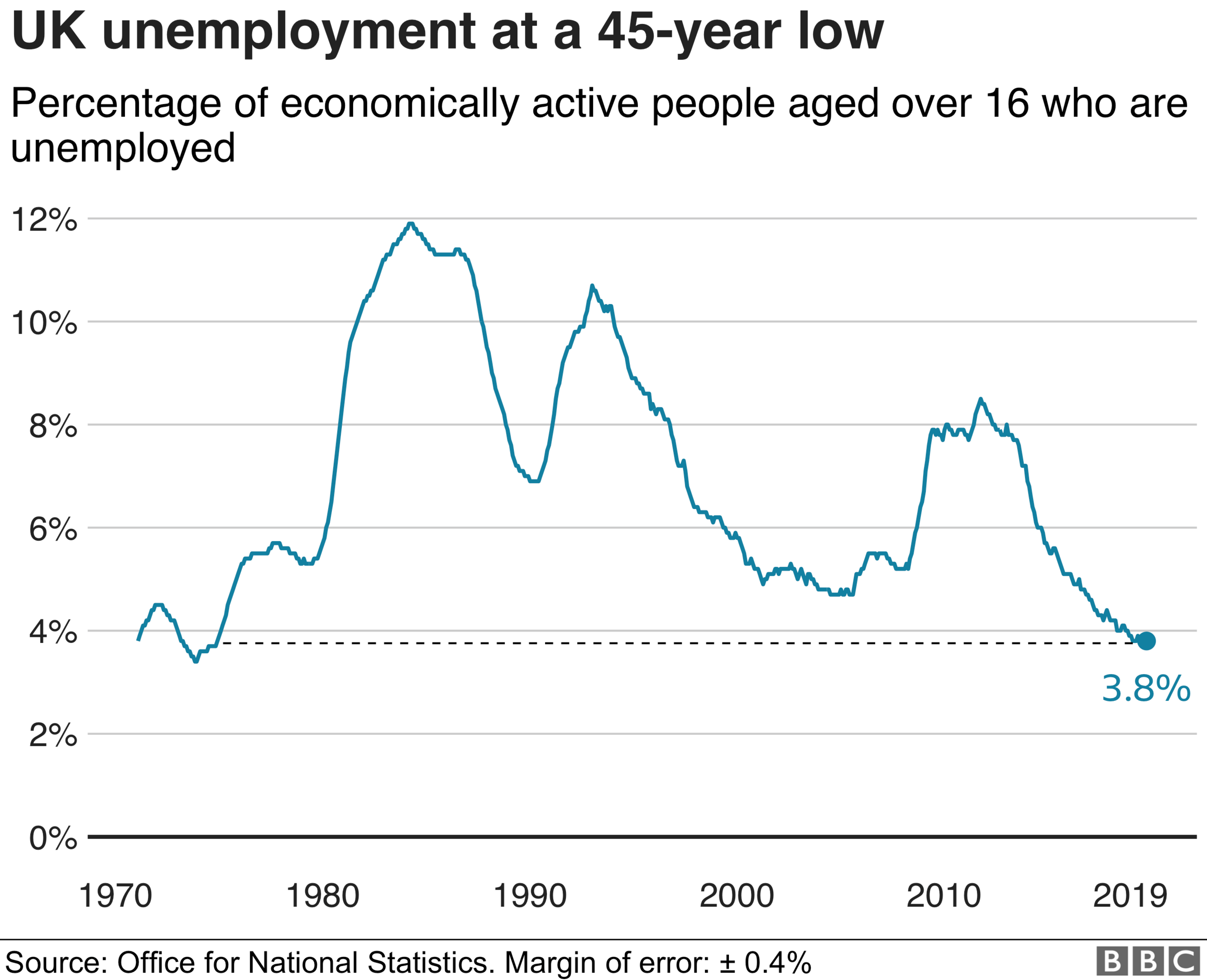

The unemployment rate was barely changed at 3.8%.

However, the number of estimated job vacancies fell to 805,000, a drop of 11,000 compared to the previous quarter and 49,000 fewer than a year earlier, undermining the generally strong picture of the labour market.

The change in the retirement age for women from 60 to 65 means that many are staying in the workforce for longer.

However, the number of working-age women in employment was also boosted by fewer women remaining economically inactive to care for children and other relatives.

Jing Teow, economist at PwC, said the overall picture was relatively positive.

"However, there are other signs that the labour market is coming off the boil. Vacancy levels remain high, but have been on a general decline since early 2019," she said.

"Wage growth has edged slightly lower from 3.5% to 3.4% for regular pay, but still well above inflation, which should continue to support consumer spending. These signs appear broadly consistent with the weaker-than-expected GDP readings for November last year."

Unemployment is one of the closely-watched metrics that guide the Bank of England in deciding whether to raise or lower interest rates.

Reporting that the number of jobs has hit a new record these days is like reporting back in the 1990s that stock markets had hit a record high. It hardly feels like news because it happens almost every time the figures come out.

Today's jobs figures, however, were surprisingly upbeat. What with the official estimates last week showing an economy that was barely growing - indeed, shrinking in November - the markets had expected perhaps 100,000 new jobs to be generated. Instead it was more than 200,000.

Similarly, the relatively healthy growth in pay was expected to slow. It did, but only a little - down from 3.5% to 3.4% excluding bonuses. After taking inflation into account, that's still a pay rise of 1.8%. Hold your breath: some day soon (but not yet) the average worker will be earning more than they did in March 2008 before the financial crash.

All of that, however, may not be enough to offset the other data pointing to a slowdown. Markets still expect, with a 65% probability, that the Bank of England will cut the official interest rate next week, back down to 0.5%, to try to counter the risk that the current economic slowdown morphs into something more serious.

Thomas Pugh, at Capital Economics, said the "solid" employment data would be likely to nudge policymakers away from a rate cut at next week's Monetary Policy Committee meeting.

"It is worth noting that the MPC has said that it is giving more weight than normal to the condition of the labour market to help it determine how much slack there is in the economy," he said.

"The rebound in employment and slightly softer pay growth will give the MPC another reason not to cut rates from 0.75% to 0.50% at their next meeting on 30th January. However, we think that the crucial piece of information for the MPC will be the flash PMIs [manufacturing data] on 24 January, which will confirm, or refute, any 'Boris bounce' in the economy."

- Published15 January 2020

- Published19 December 2019

- Published17 December 2019

- Published17 November 2019

- Published11 November 2019