Fall in inflation raises prospects of interest rate cut

- Published

- comments

Cheaper hotel costs helped to push the inflation rate down

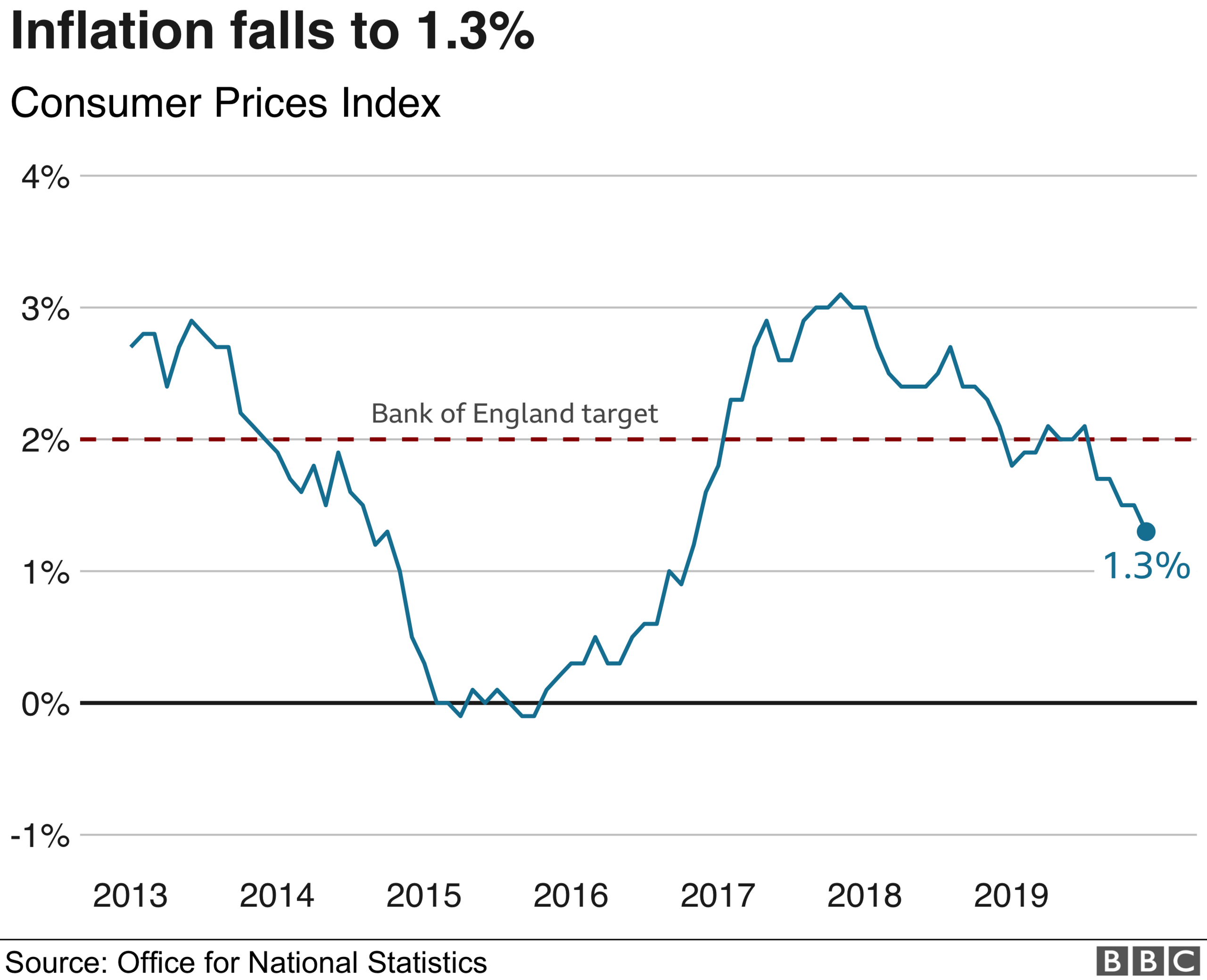

The UK's inflation rate fell to its lowest for more than three years in December, increasing speculation that interest rates could be cut.

The rate dropped to 1.3% last month, external, down from 1.5% in November, partly due to a fall in the price of women's clothes and hotel room costs.

December's inflation rate was the lowest since November 2016.

Analysts said it raised the chances of a rate cut, with inflation below the Bank of England's target of 2%.

"Very soft UK inflation data for December leaves the door wide open for a Bank of England rate cut on 30 January," said Melissa Davies, an economist at stock broker Redburn.

The Bank's main interest rate is used by banks and other lenders who set borrowing costs.

It affects everything from mortgages to business loans and has a big effect on the finances of individuals and companies.

City traders who spend their working lives trying to anticipate moves in interest rates are convinced of it today: the Bank of England is likely to cut the official interest rate when it meets later this month. Market indicators suggest a 60% chance of it happening.

Here's the thinking: at 1.3%, the official measure of consumer price inflation in the year to December was lower than expected and well below the 2% target. With the economy barely growing (even shrinking if you are prepared to rely on the official November estimate of a 0.3% contraction) there's little sign of inflationary pressure in the near future.

Granted, there was a sharp rise in the price of crude oil - a barrel was up 4.9% in the month and 17.4% on the year. But in spite of that, producers were still paying slightly less for their raw materials and supplies than they were last year.

The assumption has been that the November contraction was a temporary period of weakness induced by pre-election political uncertainty - and that there will be a recovery as businesses and consumers regain a new-found confidence to spend and invest.

The risk the MPC will have to contend with is that that hoped-for post-election recovery does not materialise.

Earlier on Wednesday, Michael Saunders, one of the rate setters on the Bank's Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), reiterated his view that borrowing costs should be lowered.

"It probably will be appropriate to maintain an expansionary monetary policy stance and possibly to cut rates further, in order to reduce risks of a sustained undershoot of the 2% inflation target," he said.

Last week, two other rate setters and Bank governor Mark Carney also suggested that rates could be cut, depending on how the economy performs.

On Sunday, MPC member Gertjan Vlieghe told the Financial Times he would consider voting for a rate cut depending on how the economy has performed since the December election.

However, members of the MPC could take the latest inflation figure with a pinch of salt, said Samuel Tombs, chief UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics.

"Half of the decline in the headline rate was driven by a sharp fall in volatile airline fares inflation," he said.

He expects inflation to rise to 1.6% in the first three months of 2020, and this could mean enough MPC members will decide to wait rather than voting to cut rates.

Emma-Lou Montgomery, associate director for personal investing at money manager Fidelity International, said the inflation data painted a bleaker picture for the UK economy than before.

"Today's UK CPI figures simply add to the growing sense of unease many feel when considering the outlook for the UK economy, with the rate of inflation continuing to lag well below the Bank of England's target of 2%."

A cut would ease the finances of borrowers, but create a tougher environment for savers, she added.

- Published13 January 2020

- Published12 January 2020