Would you eat a 'steak' printed by robots?

- Published

- comments

Most hearing aids are made by a 3D printing process

You might not know it, but if you wear a hearing aid, you are likely to be part of the 3D printing revolution.

Almost all hearing aids nowadays are produced using the technique.

Also known as additive manufacturing, 3D printing involves building up layers of material - plastic, metal or resin - and bonding them together, until eventually you have the finished product.

"Previously, production had been the sole preserve of modellers who finished each unique piece by hand in a time-consuming and costly process," says Stefan Launer, a senior vice president at Sonova, which makes hearing aids.

"Now, once an order is placed, it takes just a few days for the finished product to be delivered, and the customer receives a hearing aid with individual fit," he says.

3D-printed hearing aids can be made quickly and to individual fits

When 3D printing began to emerge 20 years ago, its boosters promised that it would revolutionise many industries.

And in many ways it has been a big success. In 2018, 1.4 million 3D printers were sold worldwide, and that is expected to rise to 8 million in 2027, according to Grand View Research.

"In terms of the technology, there are constantly new applications discovered, with new materials and machines unveiled each year," says Galina Spasova, senior research analyst at IDC Europe.

The technique has "revolutionised" the dental sector, she says, cutting the time it takes to make crowns and bridges, as well as making them more accurately.

On a bigger scale, Boeing is using 3D-printed parts in its spacecraft, commercial and defence aircraft, while BAE Systems uses the technology to make components for the Typhoon fighter.

There is even a 3D printer on the International Space Station, where it is used to create spare parts.

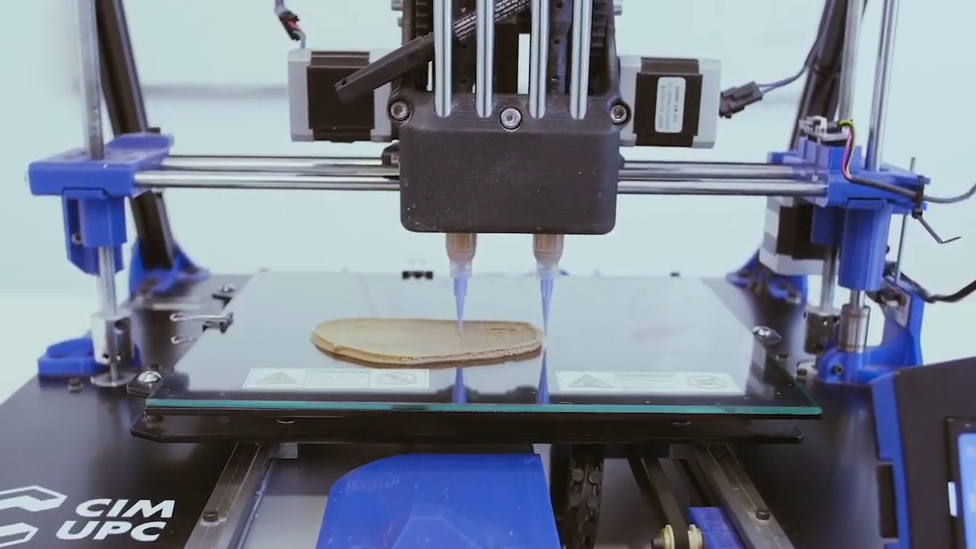

Nova's plant-based steak mimics muscle using 3D printing

But many applications are still on a smaller, experimental scale.

For example, food can be 3D printed. Barcelona-based Nova Meat recently unveiled a plant-based steak derived from peas, rice, seaweed and other ingredients.

Using 3D printing allows the ingredients to be laid down as a criss-cross of filaments, which imitate the intracellular proteins in muscle cells.

"This strategy allows us to define the resulting texture in terms of chewiness and tensile and compression resistance, and to mimic the taste and nutritional properties of a variety of meat and seafood, as well as their appearance," says Guiseppe Scionti, the founder of Nova Meat.

By next year, he says, restaurants could be printing out the steaks for themselves.

Layers of 'steak' can be laid down in a criss-cross pattern to create texture

One of the most exciting fields for 3D printing is medicine. For some time now, medical professionals have been 3D printing prosthetics, which can be made for a fraction of the usual price.

They can also be easily personalised for the individual patient - indeed, earlier this year a cat in Russia was given four 3D-printed titanium feet after losing its own to frostbite.

Medicines can be 3D printed - something that's particularly useful when treating small children, who need lower drug doses as standard.

As co-director at NIHR Alder Hey Clinical Research Facility for Experimental Medicine professor Matthew Peak points out, "The majority of medicines available to children have not been designed with children in mind or, indeed, tested in clinical trials involving children."

Last year, his team became the first in the world to give a child a 3D-printed pill; meanwhile, other researchers are creating pills that are personalised for the individual patient.

US company Desktop Metal aims to make it possible to manufacture 3D-printed parts at industrial scale.

Perhaps most extraordinary of all is the work being done to 3D print human organs. Researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in the US recently announced that they'd developed a way to 3D print living skin, complete with blood vessels, that could be used as a graft for burn victims.

There are still hurdles to overcome - the technique has been used only on mice so far, and work needs to be done to make sure the grafts aren't rejected. But, says associate professor Pankaj Karande, once grafted onto a special type of mouse, the vessels from the printed skin were able to connect with the mouse's own vessels.

"That's extremely important, because we know there is actually a transfer of blood and nutrients to the graft which is keeping the graft alive," he says.

The walls of this house were built by robots - humans are still needed to build the roof

Some hope the technology can be used on a much bigger scale.

"We believe 3D printing houses and buildings will change the way the world is built," says Kirk Andersen, chief engineer of New York firm SQ4D.

Earlier this year, his firm built a 1,900 square foot house in just eight days, by using a robot to build up the walls layer-by-layer.

The roof still has to be built by construction workers.

The process "drastically" reduces the amount of material and labour costs used in construction, according to Mr Anderson. The firm estimates that its house costs 70% less to build than an equivalent property built using traditional methods.

The technology is still under development, but a number of 3D-printed buildings have been completed around the world, giving a sense of what could one day be possible.

While 3D printing is common in car making and aerospace where the technique is valued for making prototypes, tools and parts, most of the items you buy are likely to be mass produced on production lines for some time to come.

This article is the third in a mini-series on disruptive industries. You can find the first on blockchain here and the second, on robotics here.