Why your new work colleague could be a robot

- Published

Welcome to the future of the workplace - this is robot EVA at work

You hear EVA before you see it. A whirring and whizzing noise greets you as you enter the offices of Automata, a start-up robotics company based in London.

To one side a robotic arm is going through an intricate set of moves: six joints twisting and turning in a sequence which, in the real world, would place a label on a parcel.

That's EVA, and it has being doing those moves non-stop for months to test its reliability.

Around the office and workshop there are more than a dozen other EVA units, some being dismantled by the engineers, others awaiting testing.

It must be very eerie at night as EVA continues its work, simulating attaching labels, while surrounded by its silent clones.

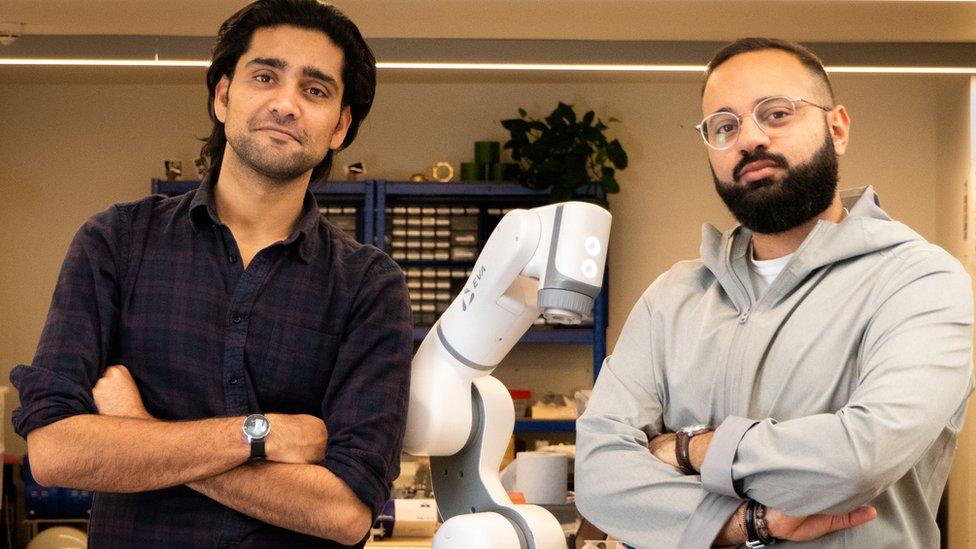

Automata founders Suryansh Chandra (left) and Mostafa Elsayed

This robotic arm emerged from the work of former architect Suryansh Chandra and his business partner Mostafa Elsayed.

"We started out with the intention to democratise robotics, to make automation accessible and affordable to as many people as needed it," says Mr Chandra.

They are betting that there are thousands, if not millions, of smaller businesses which need repetitive tasks completed, but can't afford a big industrial robot.

So EVA was developed from cheap reliable parts. It uses the same motors that power the electric windows in cars, while the computer chips are similar to those used in the consumer electronics business. This is allowing them to sell EVA at £8,000.

"If I was to give you an analogy, this was a world where there were a lot of luxury cars. Everything was fast, powerful and precise, but there was no Toyota. There was no people's car," Mr Chandra says.

Automata is just one firm trying to find a wider market for robots and disrupt the way that things are made.

More than 2.4 million industrial robots are operating in factories around the world, according to data from the International Federation of Robotics, external (IFR), which is forecasting double-digit sales growth from 2020 to 2022.

The majority of robots currently do repetitive work in large factories, producing cars, electronics and metal.

These giant industrial arms have long been powerful and accurate, but have lacked adaptability.

WATCH: A robot safely picking up pastries and cakes

Yet now, developments in artificial intelligence, alongside improved vision technology and better devices for gripping, are opening new markets.

Online shopping has given the industry a juicy opportunity. In giant warehouses millions of objects of all different shapes and sizes have to be sorted and moved around.

Pick and mix

To replace the humans in this growing market, robots need to be able to recognise and grip all sorts of different items.

"Something that a child can do easily, which is to reach into a bin and grab an item, is really hard for a robot. It's taken a ton of technology to make it possible," says Vince Martinelli, from US-based RightHand Robotics.

RightHand Robotics use suction and a gripper to grab items

His company was one of the first to develop a gripper that could be fitted to the end of robot arm, allowing it to grab items of different sizes.

Their attachment for a robot arm employs a suction device and three fingers to grab items. First the sucker extends to select the item and then the three fingers secure it.

It uses a camera linked to artificial intelligence to identify and locate the object it wants.

The explosion in online shopping has created a demand for this kind of technology; Amazon alone has invested hundreds of millions of dollars in tech for its warehouses.

"When I go to a store I provide the picking labour for free. I go around the store grabbing the things I want. If I order online I have kind of exported that labour back to the retailer and they've got to figure out now how to do the item handling," says Mr Martinelli.

Picking up delicate items has been a challenge for robots

Soft Robotics, also based in the US, is tackling the same problem albeit in a different way.

Its robotic hand has rubbery fingers that fill with air, allowing them to handle delicate food items like biscuits and pastries.

"The food industry is almost entirely manual today, because every piece of food, every chicken cutlet, you name it, varies in size shape and weight. You also have an added dimension of food safety and cleanliness," says Carl Vause, the chief executive of Soft Robotics.

Mr Vause thinks his firm's technology will also lend itself to the clothing industry.

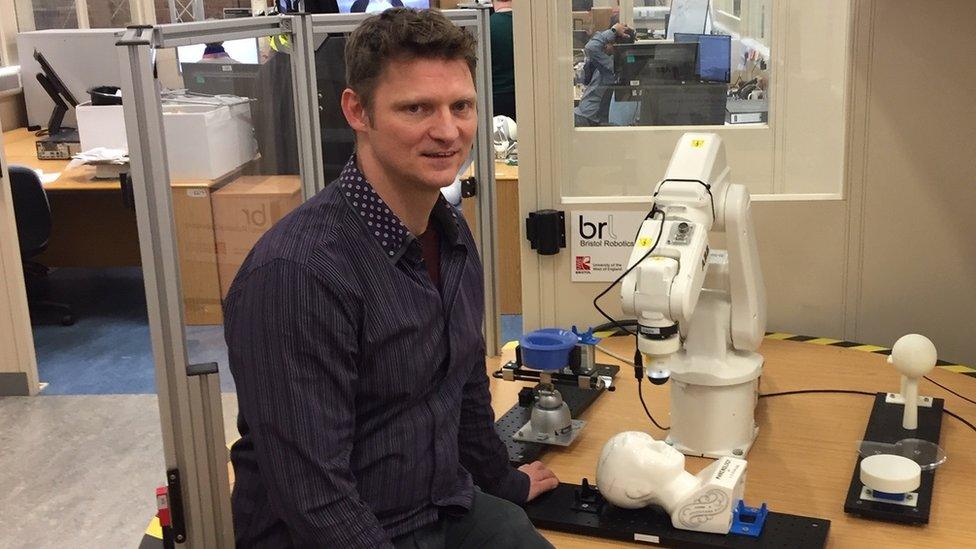

Prof Lepora says creating robot hands is "just an engineering challenge"

While such systems give robotic arms more skill, their dexterity still falls a long way short of the human hand.

Researchers at the Bristol Robotics Laboratory, external (a partnership between the University of the West of England and Bristol University) think the big breakthrough would be to give robot hands a sense of touch.

Prof Nathan Lepora, head of the tactile robotics group, has developed rubber sensors that can detect and map surfaces.

The robot that's being trained to tidy up

The system uses a camera inside each "finger" that detects how the rubber tip bulges and moves when touching an object.

Using a type of artificial intelligence called machine learning, the robot is then trained to recognise objects just by touching them and seeing how the rubber tip responds.

Prof Lepora thinks that by the end of this decade robots will be able to manipulate items, assemble objects and tinker in the same way that humans do with their hands.

"It is just an engineering challenge at the end of the day. There's nothing magical about how we use our hands," he says.

Up to one-third of all jobs could be "radically transformed" by automation, says the OECD

'Emotional reaction'

Future developments in robotic hardware and artificial intelligence mean that robots will be able to do more and more of the jobs that are currently performed by humans.

According to a report by the OECD, external, 14% of of jobs are "at high risk of automation" and 32% of jobs could be "radically transformed", with the manufacturing sector at the highest risk.

It's a sensitive topic for those that work in the robotics industry and companies that use robots.

Mr Chandra argues that his technology will eliminate boring, repetitive jobs that humans don't like and aren't very good at, and also create new ones that are likely to replace them.

"There's definitely tens of thousands of new jobs that exist to suit the current society that did not exist before. So I think this constancy of jobs is a fiction, it's never really been the case," he says.

Every time a job dies, there is an emotional reaction... but every time there's a creation of a new economy."

Follow Technology of Business editor Ben Morris on Twitter, external

This article is the second part of mini-series on disruptive technologies, you can find the first, on blockchain, here.