The women who make argan oil want better pay

- Published

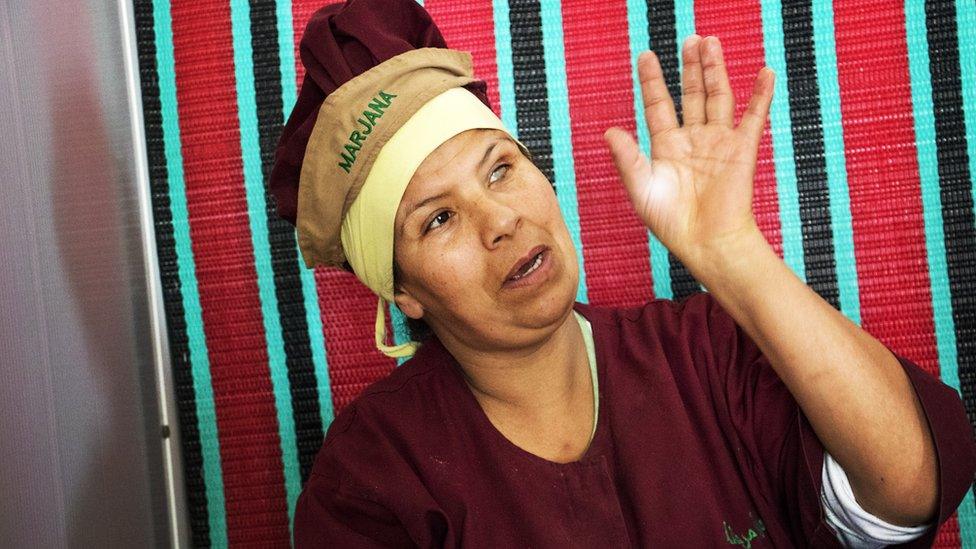

Samira Chari says that extracting the argan seeds is the only job she can find

Whether it is being drizzled on salads or turned into face creams, Morocco's argan oil is the latest culinary and cosmetic must-have. But with sales soaring around the world, concerns remain about the pay and conditions of the mainly female workforce that produces the oil.

I watch as a group of women each use two rocks, one large, one small, to smash open the fruit to get to the seeds inside a very hard central nutshell.

They sit on cushions on the floor of a cool stone house, beside big piles of the fruit.

"I want a better job, with a better salary," says one of the workers, 37-year-old Samira Chari. "But there is nothing else. This is my only option."

The argan tree is native to Morocco

We are in the Moroccan countryside, some 25km (15.5 miles) inland from the port city of Essaouira, halfway down the country's Atlantic coast. It is warm and sunny, and lush green argan trees pepper the arid landscape.

The women are employed by a business called Marjana, one of around 300 small firms, mostly co-operatives, that now produce argan oil by extracting it from the seeds. The trees themselves, which are up to 10m (33 ft) tall, are found all over Morocco.

Often called the country's "liquid gold", global sales of argan oil are soaring, helped by studies that suggest it has health benefits. Production, which is almost all from Morocco, is expected to reach 19,623 US tons or $1.79bn (£1.4bn) by 2022, external up from 4,836 US tons in 2014.

In Morocco argan is traditionally used as a foodstuff - a dip for bread or drizzled on couscous - and as a medicine. But the big growth in demand is being led by the worldwide cosmetics industry. In addition to face creams, it is now being added to products like lip gloss, shampoo, moisturisers and soaps.

To get to the seeds, the flesh of the fruit, and then a hard nutshell, have to be removed

The women who harvest the seeds are more often from the Berber ethnic group, and this is the case at Marjana, where staff manager Amina Bouna says they bring age-old skills.

"Only Berber women know how to extract the oil," she says. "It's old Berber knowledge. Otherwise we have all types of women here - young, old, married and divorced."

The 80 women at the company are allowed to work as much as they like. But despite many working from early mornings until evenings, they normally make less than $221 (£170) a month, says Ms Bouna - below Morocco's recommended national minimum wage.

"But it's better than they stay at home," argues Ms Bouna. "Before, they made the oil at home. Their husbands sold it on the market and kept the money. Now they don't need their husbands' money, as they make their own. It's a win-win situation."

In Morocco, the oil is more often used as a dip for bread

The workers do get some health insurance and pensions provision, but Ms Chari wants to see wages go up. Divorced, she says she has to work long hours to afford medicine for her daughter. She says if she were paid more, she'd be able to spend more time with her child.

As the industry becomes more lucrative, the issue of the women's wages has become an increasingly hot topic. Zoubida Charrouf, a chemistry professor at Mohammed V University of Rabat is one of the leading advocates for higher salaries.

Argan oil is increasingly used in cosmetics products

Prof Charrouf, who also helped to fuel the growth in argan oil sales after publishing studies into its health benefits, says that salaries can be as low as $50 a month.

She adds that some of the companies prefer to pay taxi and bus drivers to bring tourists to their facilities so that they can sell them the oil, rather than pay the workers properly.

The situation has become such an issue in the country that Morocco's minister of agriculture asked Prof Charrouf for help in forcing firms to join industry trade bodies, and commit to paying staff the minimum wage.

Argan facts

Local goats still climb argan trees to eat the fruit

The goats cannot digest the nuts and the seeds within them, and instead they pass through their systems. In some communities, the nuts would then be picked from the goat excrement, much like the civet coffee bean, but these days humans harvest the fruit before the goats can get at them

The trees have very deep root systems to access water

It takes 40kg of dried fruit to produce one litre of oil

Prof Charrouf says that this work has now started near the city of Agadir, 175km south of Essaouira, and is due to expand north. "The women are not happy, and need help to fight," she adds.

The Ministry of Agriculture did not respond to requests for a comment.

Khadija Tiktoutj says she likes the job

Prof Charrouf says she is also concerned by the rise of industrial argan oil production, where the oil is extracted mechanically on a large scale, driving down prices.

Oil produced this way can cost as little as $22 a litre, less than half the cost of oil made by the small co-operatives.

However, she adds that she is pleased that cosmetics giant L'Oréal has pledged to buy all its argan oil from small co-operatives that sign up to fair trade principles., external

Global Trade

Back at Marjana, 55-year-old employee Khadija Tiktoutj is much less downbeat about her job harvesting the seeds than her colleague Samira Chari. Ms Tiktoutj started working there in 2008, after previously being employed elsewhere as a cleaner.

"Argan is a local product, and I really wanted to work with that," she says. "As a cleaning lady, I also did not have health or pension insurance. Now my son can go to university, and I can buy what I need."