'I have to live on $1,175 a year'

- Published

Fruit picker Carmen Priscilla says she has to live on just $1,175 (£901) per year

After a decade working on a fruit farm, Lucas da Silva says he couldn't take it any more.

"I felt that I was working like a slave," says the 25-year-old.

Mr da Silva spent 10 years spraying pesticides on melon plants in north eastern Brazil, until he quit at the start of last year.

He says he was never offered sufficient protective clothing, and that his health suffered as a result. "By the end of the day I always had a headache due to contact with the products.

"You couldn't even wash your hands before meals," he adds. "We did not have water or soap."

Brazil is one of the largest producers of table grapes, from vines that are often sprayed with pesticides, as here

Stories like this are not uncommon among the vast number of Brazilian farm workers who help plant, grow and harvest fruit - such as mangoes, melons, grapes and oranges - that often end up on the shelves of supermarkets across Europe and North America.

Brazil is the world's third-largest fruit producer, behind only China and India, and ahead of the US. For oranges it is in first place, with almost one out of every four oranges consumed worldwide coming from Brazil.

In total, 4.8 million Brazilians are paid farm workers, according to the National Confederation of Rural Workers trade union. And Brazil's fruit production is booming.

The sector generates 40bn Brazilian reais ($10bn; £7.3bn) of sales a year, according to Brazil's economics ministry. The problem, according to a report by the charity Oxfam Brazil, is that nowhere near enough of that money goes to the workers.

The study, Sweet and Sour- An investigation of conditions on tropical fruit farms in North-East Brazil, external, found that fruit workers were among the poorest 20% of Brazilians. It also detailed evidence of poor working conditions, such as those experienced by Mr da Silva.

Brazilian fruit workers complain of poor pay and working conditions

In the peak picking season for Brazilian mangoes, September and October, half of all the mangoes on sale in the UK come from Brazil. At the start of the supply chain are the pickers, who more often are women.

Carmen Priscila Souza, 25, is one of them. From the state of Rio Grande do Norte, she has been doing the job since she was a teenager. While Brazil does have a minimum wage, she can only find work in the five months of the year when there is fruit to be picked.

So she earns just $1,175 (£901) to last the whole year. "For any workers this value is very little," she says. "But it is better than standing still for nothing."

Gustavo Ferroni, a Sao Paulo-based researcher who co-authored the report for Oxfam, says the problem has been exacerbated by the fact that the Brazilian agricultural sector is dominated by giant companies, at the expense of smaller producers.

He says that an added barrier to seeing wages and working conditions improve is that people are scared of losing their jobs.

"The argument that any job is better than no job puts on workers the burden of accepting any working condition, and exempts economic sectors from their responsibilities," he says. "That is not fair. The fruit chain generates wealth and it needs to be better distributed."

This Brazilian fruit farm worker says that his chronic skin condition was caused by his extensive exposure to the pesticides he used to spray onto crops

Oxfam is calling on the Brazilian government to increase the country's minimum wage, reinforce inspections of farms to ensure that workers are not being mistreated, allow employees to more easily join trade unions and review recent approvals of agro-chemicals.

Economist Patricia Pelatieri says that the current Brazilian minimum wage of 998 reais a month is "far from enough". She adds: "The minimum needed per month for people in north eastern Brazil would be around 1,800. And they should receive it for the 12 months of the year."

The Brazilian government was approached to provide a comment for this article, but the Ministry of Agriculture refused to answer any questions, and the Ministry of Work did not reply.

Global Trade

One of the large agricultural companies criticised in the Oxfam report is Caliman. It says that it "doesn't acknowledge the reality portrayed by the report".

Countries in western Europe are the biggest buyers of Brazilian fruit, accounting for 67% of all overseas sales. This is led by the Netherlands and the UK.

The Oxfam report calls on supermarkets in both countries to more closely monitor the source and supply chain of their Brazilian fruit, and put pressure on producers and suppliers to boost working conditions.

It also asks that the supermarkets work more with Brazilian trade unions, something it praises UK giant Tesco for doing.

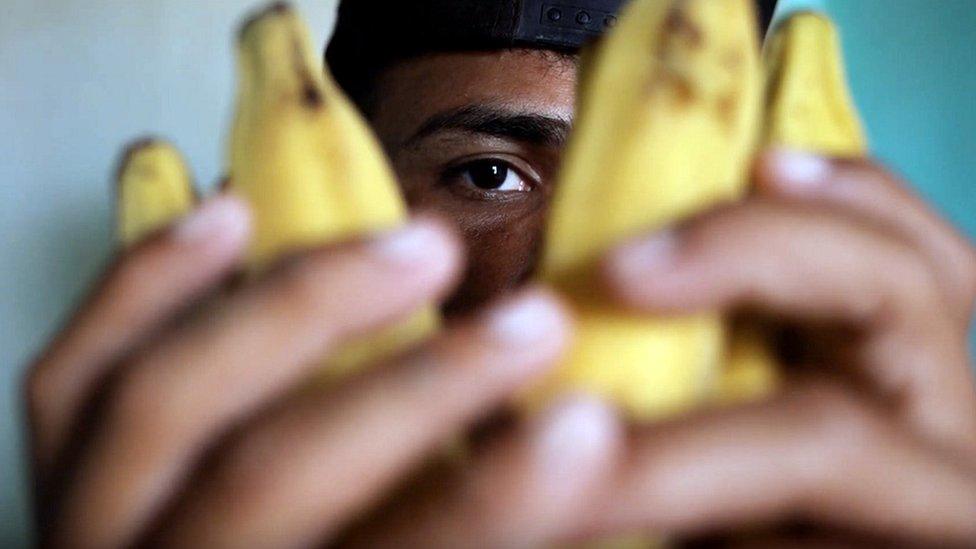

Brazil is also the world's fourth-largest producer of bananas, but most are sold domestically

Back in the state of Bahia in north eastern Brazil, Jose Evandro da Silva has now been out of work for almost a year.

"When I decided to leave the company, the manager called me into his office and told me that if I decided to sue them, no other company in the region would hire [me]," he says.

Mr da Silva didn't go down the legal route. Instead he is hoping to get work at a new wind farm that is due to be constructed in his region.