Brexit divorce: Five key things the UK must navigate

- Published

After cohabiting with the European Union (EU) for 47 years, the UK is now free to play the field.

But as is already clear, wooing new suitors while also trying to keep a civil footing with the ex will be tricky.

With less than one year to thrash out a trading deal, here are five things the UK now has to work out.

1) Who does the UK want to be?

The UK is going to have to decide quickly which of its ex-partners' conditions it can live with - and which it is prepared to battle.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson's vision for a global Britain is clear: open for business with an overhauled immigration system that puts "people before passports".

It's not just about attracting investment. The government wants to be seen as the champion of free trade, especially as it takes its seat at the World Trade Organisation, which sets and polices the default rules of global trading.

The UK's break from the EU means it can have a bigger say over some regulations and standards.

But exercising that freedom may mean many bumps in the road - and some potentially costly diversions.

2) What about the ex?

Free or not, the UK does about half of its trade with the EU and maintaining that relationship is key.

But the UK's desire to flaunt its liberty complicates that.

The greater the freedom to diverge from the EU, the greater the red tape which could mean more hassle and higher costs.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson

The Withdrawal Agreement referred to a level playing field - that is, the UK not to have an advantage by undercutting the EU on state aid, environmental or labour protections or tax.

But the prime minister wants to cut loose from that while claiming it won't be a race to the bottom.

The UK also wants the right to diverge from EU rules on product standards.

Both are abhorrent to the EU and risk ruling out a zero-tariff deal.

3) Where will the UK look for love next?

The desire to break away from EU rules and standards may be a negotiating pawn but it would allow the UK to be closer to others, crucially the US.

The UK sells more goods and services to the US than to anywhere else and hosts more than half of the regional corporate headquarters of American-owned firm, making closer ties attractive.

President Donald Trump claims a US-UK deal will be "massive", but for whom?

Both want greater access to the other's markets. The US wants its drug companies and service providers to have more access to the NHS - something the Conservative manifesto ruled out.

And the US wants more opportunities for its farmers which would mean relaxing agriculture and food hygiene standards.

Mr Johnson says others have to accept the UK's standards - but is that a red line?

US President Donald Trump says a trade deal with the UK will be 'massive'

Giving way may mean lowering standards in a way that would be incompatible with EU rules, highlighting the dilemma the UK faces over whom it wants to align with.

To complicate issues, while talks with the EU and US will run simultaneously, they come under different Whitehall departments: the Cabinet Office and Department for International Trade respectively.

4) What about other suitors?

The UK wants new trade deals with "neglected" friends, including Canada and Australia and also to finish replicating ones the EU has with about 70 countries.

So far it has completed about 50 of the latter. The remainder include Japan, which accounts for about 2% of exports but has great strategic importance as one of the UK's biggest foreign investors.

And the UK is thinking longer term.

Africa accounts for less than 3% of UK trade. But with a quarter of the world's population set to live there by 2050, the UK has been on a charm offensive, recently hosting the first African Investment Summit.

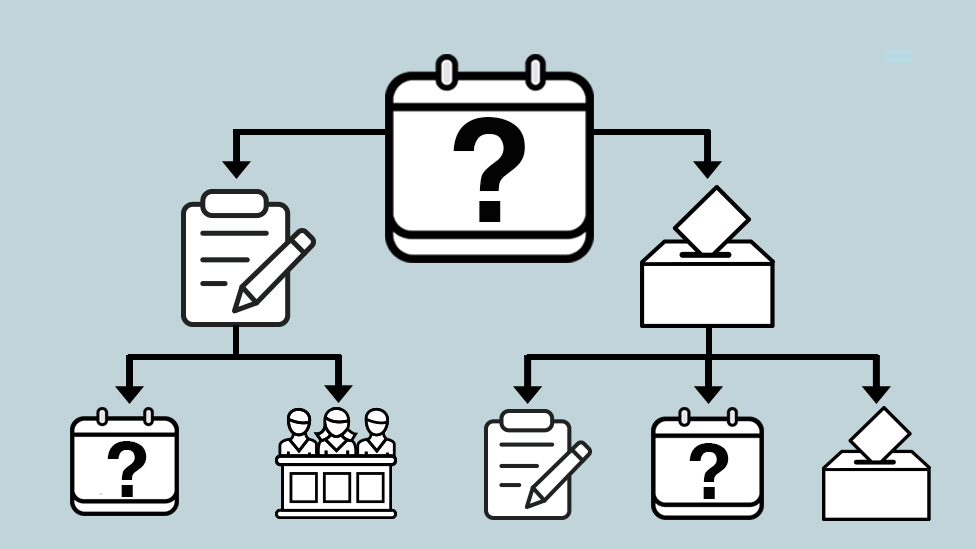

5) When will things settle down?

What are the chances of a deal being done with the EU by the end of 2020?

It will require compromise.

Negotiating the EU's trade deal with Canada took over five years. Given the complexities here, there may be only the first stage of a deal, to cover goods and agriculture, by December. Or the prime minister may have backpedalled and asked for more time.

And that's just the deal with the EU.

It could be quite a while before we know what shape the UK's new blended global family will take.

- Published23 December 2021

- Published13 July 2020

- Published26 January 2024