Coronavirus: US central bank makes emergency rate cut

- Published

- comments

Fed Chair Jerome Powell

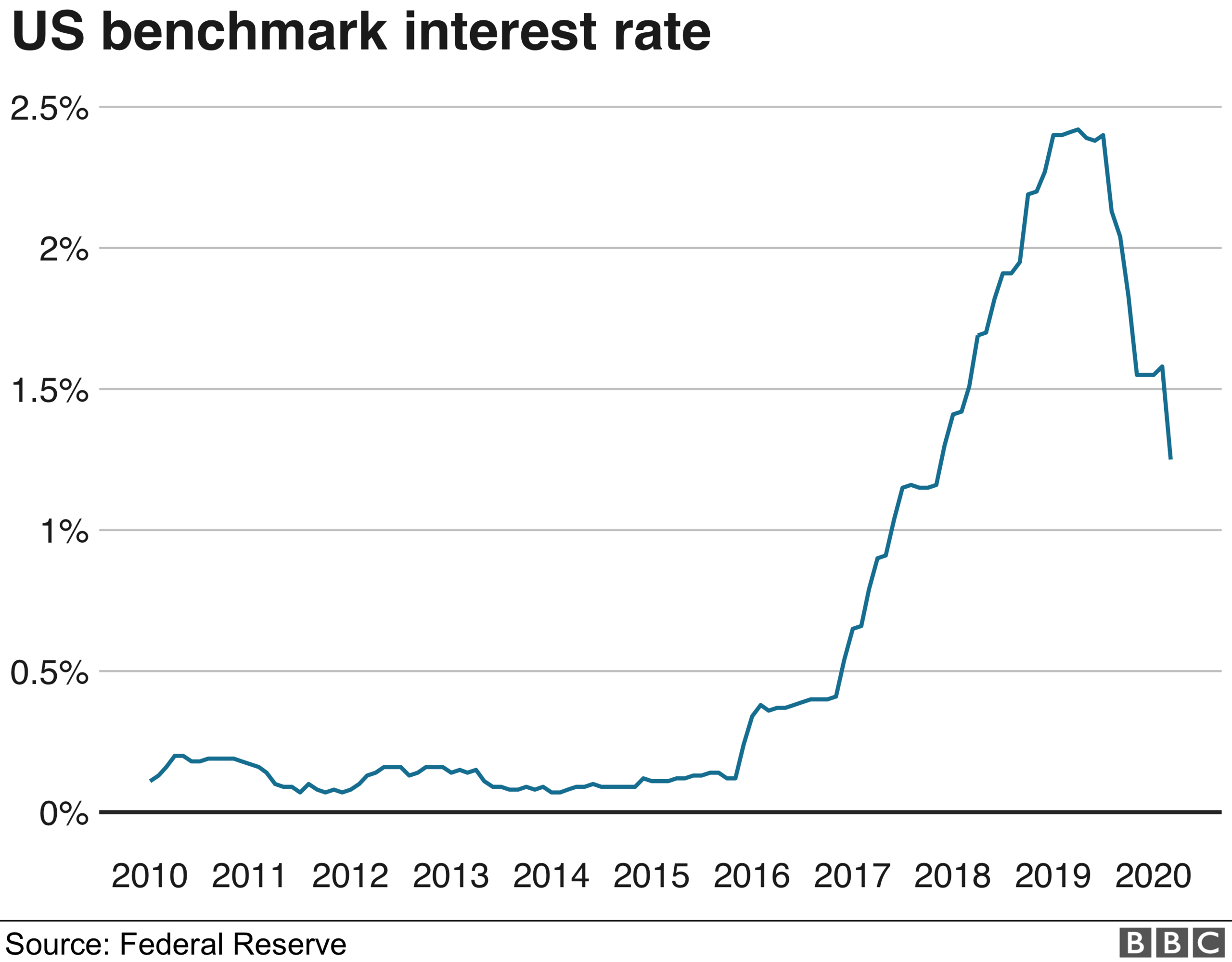

The US central bank has slashed interest rates in response to mounting concerns about the economic impact of the coronavirus.

The Federal Reserve lowered its benchmark rate by 50 basis points to a range of 1% to 1.25%.

The emergency move comes after the G7 group of finance ministers pledged action earlier on Tuesday.

It follows warnings that slowdown from the outbreak could tip countries into recession.

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said the US economy remains strong but it is difficult to predict the "magnitude and persistence" of the effects of the spreading virus.

"The virus and the measures that are being taken to contain it will surely weigh on economic activity for some time, both here and abroad," he said at a press conference in Washington.

"We don't think we have all the answers. But we do believe that our action will provide a meaningful boost to the economy."

The last time the bank made an interest rate cut at an emergency meeting was during the global financial crisis of 2008.

The unanimous decision is a "dramatic turnaround from last week", when many Fed officials appeared confident that rates, already low by historical standards, would not need to be cut further, said Paul Ashworth, chief US economist at Capital Economics said.

"With financial markets in turmoil and evidence growing that the coronavirus is developing into a pandemic, the Fed's change of heart is entirely understandable," he said.

Mr Powell said the bank believed the rate cut would help strengthen consumer and business confidence, and keep money flowing.

Many analysts in recent days had said they expected the Fed to act.

However, Peter Tuchman, a stock trader at Quattro Securities, said he did not think financial markets would necessarily welcome the move. "They're doing it to support the markets but that makes people fearful that we must be in bad shape," he told the BBC.

"To pull that bullet out so fast and so furiously leaves us with not that much ammo," he said.

The US central bank has cut rates amid concerns about the economic impact of coronavirus.

Global action

Earlier on Tuesday, both Australia and Malaysia cut interest rates as a result of the outbreak, while finance ministers from the G7 group of nations pledged to use "all appropriate policy tools" to tackle the economic impact of coronavirus.

The group of major economies said in a joint statement they were monitoring the outbreak and ready to deploy "fiscal measures".

On Monday, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) warned the global economy could grow at its slowest rate since 2009 this year because of the virus.

The influential think tank forecast growth of just 2.4% in 2020, down from 2.9% in November, but it said a longer "more intensive" outbreak could halve growth and tip many countries into recession.

Growth concerns contributed to sharp falls on major stock markets last week, but shares had started to rebound on Monday amid signs that governments and major central banks would work together to tackle the economic hit of coronavirus.

On Tuesday, shares briefly rallied on the decision before turning negative.

US President Donald Trump has repeatedly called on Mr Powell to lower interest rates, ignoring tradition that presidents stay quiet on bank policy to preserve the bank's independence.

Following the bank's announcement, he said it should cut further. "It is finally time for the Federal Reserve to LEAD. More easing and cutting!" he Tweeted.

Mr Powell denied that the bank had been influenced by political considerations. But he kept the door open to further cuts.

Satyam Panday, senior US economist at S&P Global Ratings, said the Fed "did well by acting decisively and moving sooner".

"Given that monetary policy works with a lag, cutting now will help speed up recovery when the coronavirus concerns have passed," he said. "If the rout in the financial market continues, more rate cuts are likely to follow in the upcoming March policy meeting, and beyond if required."

Analysis:

Andrew Walker, BBC economics correspondent

First the G7 finance ministers and central bank governors told us they would use all appropriate policy tools. Not much more than an hour later, the Fed acted. Will it help?

Jerome Powell said it could avoid what he called a tightening of financial conditions - higher borrowing costs for businesses and households, banks becoming more reluctant to lend and being less willing to give some leeway to businesses with cash flow problems.

Those are real risks if the disruption were to get more serious. Mr Powell also said it could boost confidence. But it doesn't look like it will help much with the most direct economic damage. A rate cut now is probably not going to make people more enthusiastic about getting on a plane.

Nor is it much direct help for firms struggling with shortages of components due to transport disruptions. Mr Powell acknowledged that a rate cut would not "fix a broken supply chain".

The main effort in this crisis is for health agencies. But we can expect to see more actions from finance ministries and central banks seeking to mitigate the economic impact.

- Published3 March 2020

- Published3 March 2020

- Published6 October 2021

- Published28 February 2020

- Published18 February 2020

- Published30 January 2020