Budget 2020: UK public finances 'vulnerable' to borrowing shock

- Published

The OBR says the UK economy is on course to grow at the slowest pace since the financial crisis this year

A surge in public spending risks exposing the UK economy to a shock rise in borrowing costs, according to the government's spending watchdog.

Abandoning long-term goals to balance the books could have consequences, the Office for Budget Responsibility said.

Higher annual borrowing and overall debt would leave Britain "vulnerable" to changing investor sentiment.

The warning came as the chancellor unveiled the biggest Budget giveaway since 1992.

Rishi Sunak's first budget included an extra £7bn to support workers and businesses affected by the coronavirus and at least £5bn to help the NHS cope with the outbreak. In total he outlined £30bn of extra spending this year.

But higher spending over the long-term would be likely to lead to higher borrowing, which could prompt a rise in the cost of that borrowing.

Slower growth

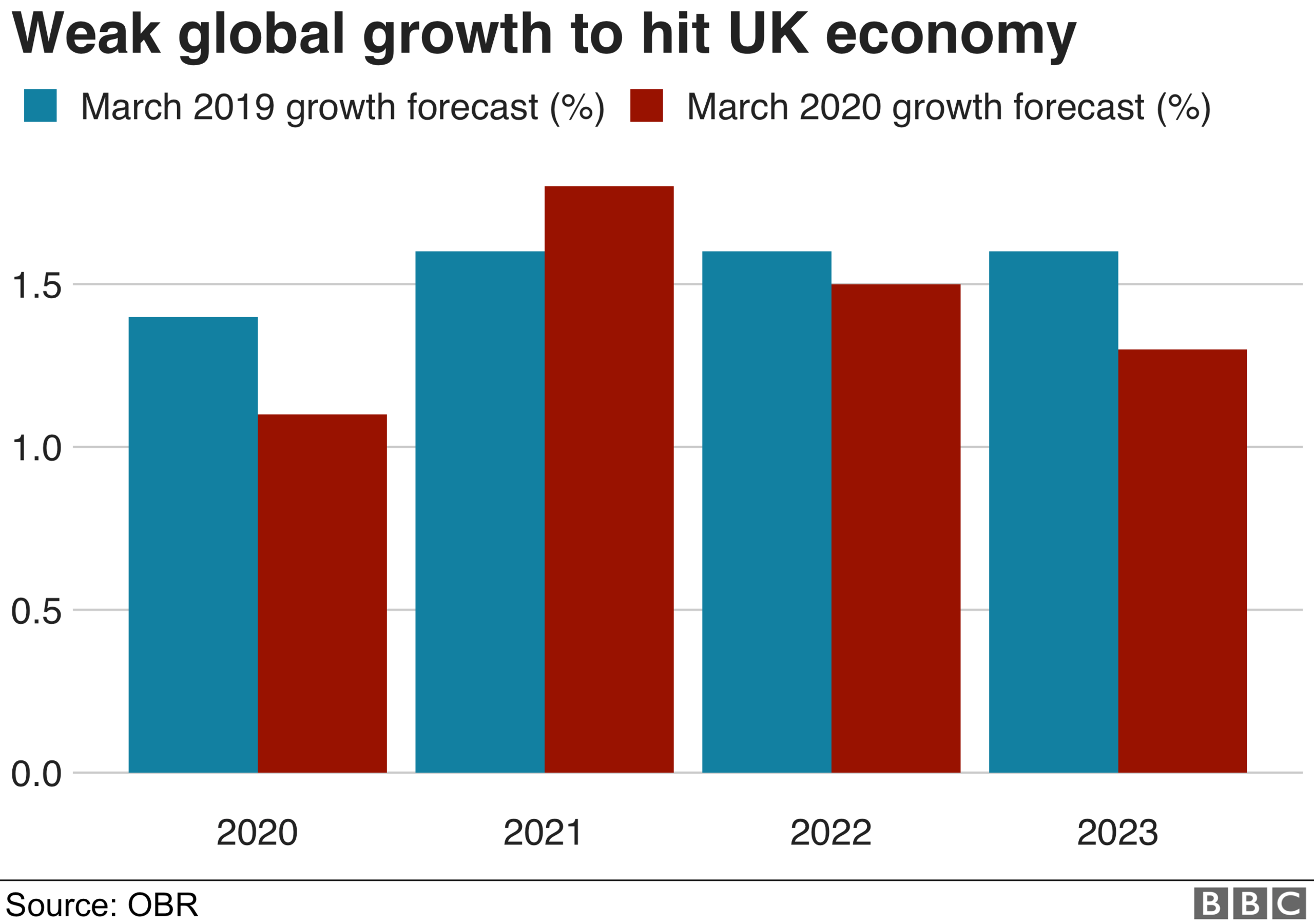

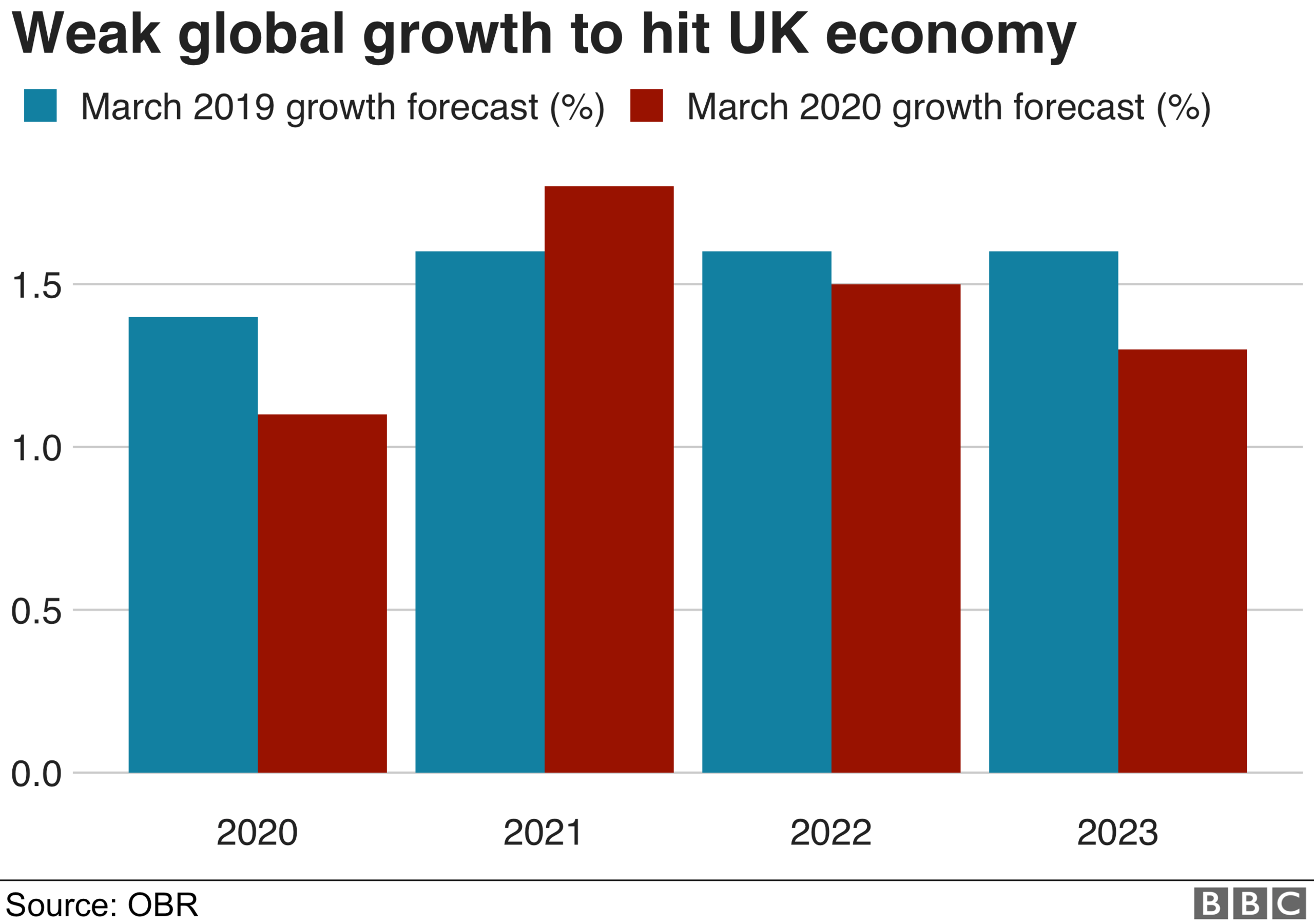

A year ago, the OBR predicted the UK economy would grow by 1.4% this year. Now it says it expects it to grow at just 1.1% this year, the slowest pace since the financial crisis.

That does not take into account any hit from the virus, which will slow growth further and could add an additional £6bn to the deficit over the next two years, George Buckley, chief UK economist at Nomura estimates.

The extra £12bn to battle the coronavirus was not costed in this year's Budget, he points out.

Public borrowing is already forecast to climb to a six-year high by 2022 without taking into account these additional spending measures.

Budget gamble?

There has been no immediate impact on the cost of government borrowing. Yields on ten year government bonds rose only marginally after the Budget as investors took the near-term planned rise in borrowing in their stride

Ranko Berich, head of market analysis at Monex Europe, said: "Markets are not only willing to accept [higher] fiscal spending but are now actively cheering it."

However, the OBR said the government's decision to move away from trying to reduce Britain's debt in relation to the size of the economy, could store up problems for the future.

The last government said it aimed to bring down public sector net debt, but it now is projected to remain steady at around 75% of GDP over the next five years.

Robert Chote, the chairman of the OBR, said that while he did not see the government spending splurge as a "gamble", a sudden increase in inflation and interest rates would make "the arithmetic a lot more uncomfortable."

Sir Charlie Bean, a member of the OBR's budget responsibility committee, added: "Clearly the more debt you build up, the more exposed you are if things go wrong.

"And there's a good general principle that you want to have the debt-to-GDP ratio declining in good times, to build up the space for responding precisely to the events like the coronavirus.

"If you only have the ambition to keep debt constant as a proportion of GDP, every time you get a bad shock, you just ratchet that up again."

Boris Johnson's government has moved away from an previous Tory ambition to eliminate borrowing this decade.

In the Budget the chancellor launched a review of the government's current self-imposed spending rule, which requires it to balance the books, excluding investment spending, within three years.

More on Budget 2020

Borrowing breakdown

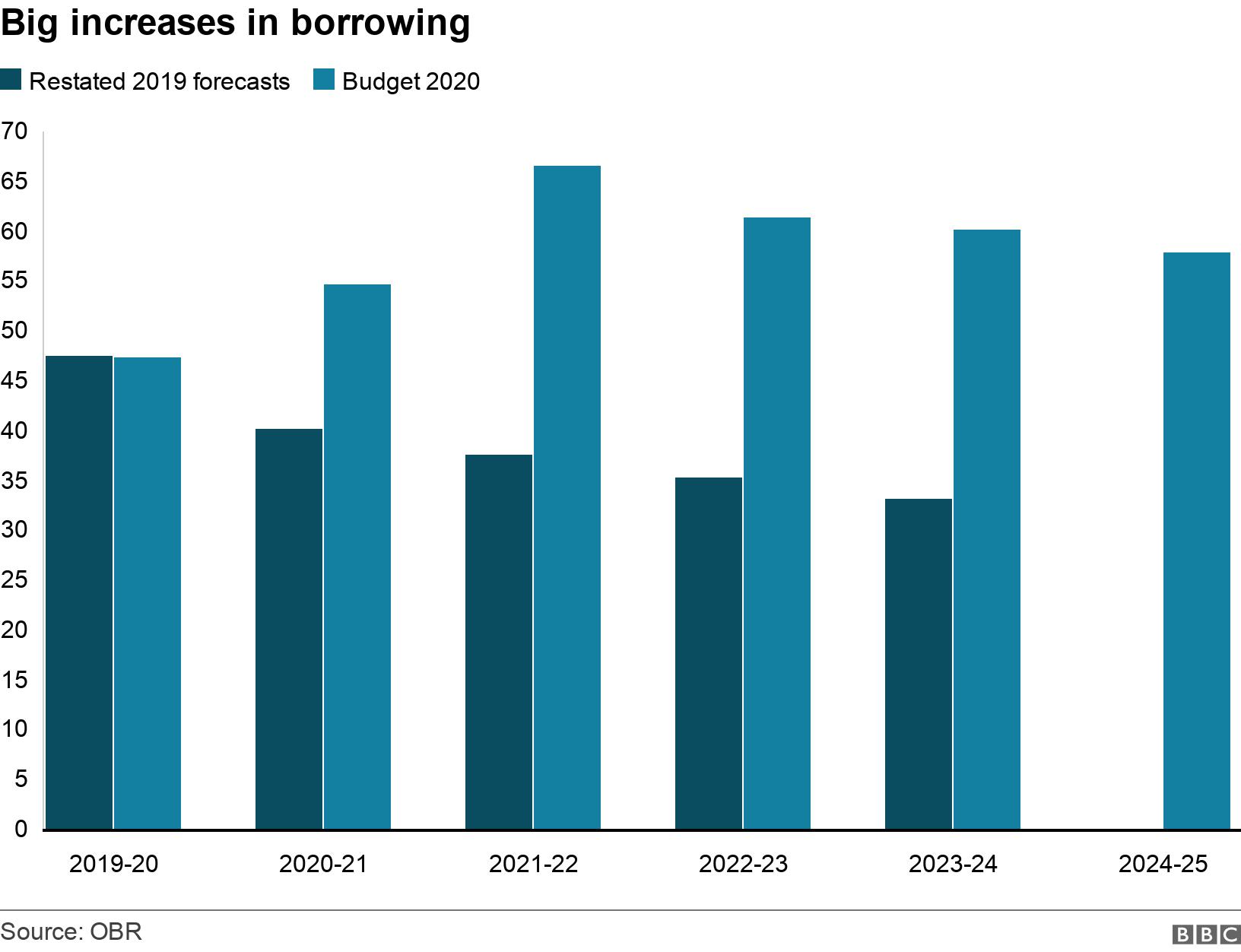

Public borrowing is forecast to be lower this financial year at £47.4bn than predicted last March, but after that the deficit is projected to rise sharply.

The government is now set to borrow £54.8bn in the coming financial year to plug the gap between the money it spends on public services and the tax revenues it collects. This is much higher than the £40.2bn that was forecast.

This will rise to £66.7bn in 2021-22.

The spending in this Budget is being largely paid for with a big increase in government borrowing.

The government expects to borrow almost £100bn more in this Parliament (before mid-2024) than was expected the last time we had any forecasts.

And that figure does not include £12bn to be spent on getting the economy through the coronavirus outbreak.

The Treasury documents say that money will be accounted for in the next Budget in the autumn.

Mr Sunak said a weaker global backdrop would drag down UK growth. But the OBR said it expected the economy to rebound in 2021 with the help of the big spending boost.

It said growth is forecast to rise to 1.8%, before moderating to 1.5% in 2022 and 1.3% the following year. Higher growth would make it easier to reduce debt as a proportion of the overall size of the economy and make the UK less vulnerable to a shock rise in borrowing costs.

However, the growth forecasts were made before the extent of the coronavirus outbreak in the UK became clear. So they do not take into account the impact of the virus, the emergency government stimulus measures, or the cut in UK interest rates announced earlier on Wednesday.

Fighting the virus

Mr Sunak said the coronavirus outbreak would have a "significant impact" on the economy, warning that a fifth of Britain's workforce could be off work at the same time during the peak of the outbreak.

But he said the extra spending and investment would provide "security today" and "prosperity tomorrow".

Mr Sunak unveiled a three-point plan to tackle the coronavirus, including:

Providing the NHS with unlimited financial resources to fight the virus

Extending sick pay benefits to healthy people forced to self-isolate as well as the UK's five million self-employed

Pledging to foot the sick pay bill for any business employing less than 250 people for up to 14 days, and scrapping business rates for small firms.

Mr Sunak said the government would do "everything we can to keep this country and our people healthy and financially secure".

- Published11 March 2020