Coronavirus: Robots use light beams to zap hospital viruses

- Published

The UVD robot takes about 20 minutes to treat a room

"Please leave the room, close the door and start a disinfection," says a voice from the robot.

"It says it in Chinese as well now," Simon Ellison, vice president of UVD Robots, tells me as he demonstrates the machine.

Through a glass window we watch as the self-driving machine navigates a mock-hospital room, where it kills microbes with a zap of ultraviolet light.

"We had been growing the business at quite a high pace - but the coronavirus has kind of rocketed the demand," says chief executive, Per Juul Nielsen.

He says "truckloads" of robots have been shipped to China, in particular Wuhan. Sales elsewhere in Asia, and Europe are also up.

"Italy has been showing a very strong demand," adds Mr Nielsen. "They really are in a desperate situation. Of course, we want to help them."

Powerful UV light is already a proven means to kill microbes

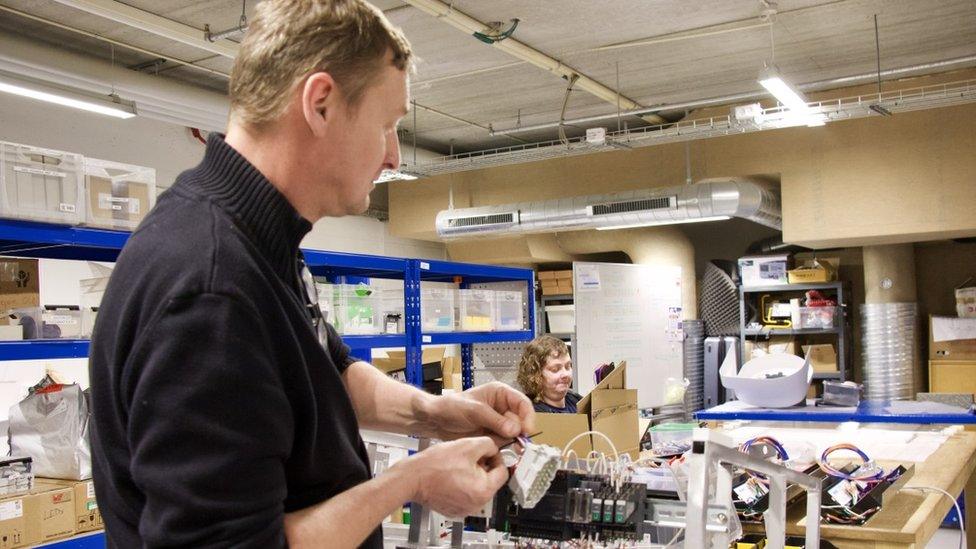

Production has been accelerated and it now takes less than a day to make one robot at their facility in Odense, Denmark's third largest city and home to a growing robotics hub.

Glowing like light sabres, eight bulbs emit concentrated UV-C ultraviolet light. This destroys bacteria, viruses and other harmful microbes by damaging their DNA and RNA, so they can't multiply.

It's also hazardous to humans, so we wait outside. The job is done in 10-20 minutes. Afterwards there's a smell, much like burned hair.

"There are a lot of problematic organisms that give rise to infections," explains Prof Hans Jørn Kolmos, a professor of clinical microbiology, at the University of Southern Denmark, which helped develop the robot.

"If you apply a proper dose of ultraviolet light in a proper period of time, then you can be pretty sure that you get rid of your organism."

He adds: "This type of disinfection can also be applied to epidemic situations, like the one we experience right now, with coronavirus disease."

UVD has tripled output of its disinfecting robots

The robot was launched in early 2019, following six years of collaboration between parent firm, Blue Ocean Robotics and Odense University Hospital where Prof Kolmos has overseen infection control.

Costing $67,000 (£53,370) each, the robot was designed to reduce the likelihood of hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) which can be costly to treat and cause loss of life.

While there's been no specific testing to prove the robot's effectiveness against coronavirus, Mr Nielsen is confident it works.

"Coronavirus is very similar to other viruses like Mers and Sars. And we know that they are being killed by UV-C light," he says.

Dr Lena Ciric, an associate professor at University College London and expert on molecular biology, agrees that UV disinfection robots can help fight coronavirus.

Disinfection robots are no "silver bullet", says Dr Ciric. But she adds: "These [machines] provide an extra line of defence."

"We're in the run up to having a lot of coronavirus patients in the various hospitals. I think it's wise to be on top of the cleaning regimes… from an infection control point of view. "

To be fully effective, UV needs to fall directly on a surface. If lightwaves are blocked by dirt or obstacles, such shadow areas won't be disinfected. Therefore manual cleaning is needed first.

UV light has been used for decades in water and air purification, and used in laboratories.

But combining them with autonomous robots is a recent development.

Xenex also has a device which uses UV light

American firm Xenex has LightStrike, which has to be manually put in place, and delivers high-intensity UV light from a U-shaped bulb.

The company has seen a surge in orders from Italy, Japan, Thailand and South Korea.

Xenex says numerous studies show that it's effective at reducing hospital-acquired infections and combating so-called superbugs. In 2014, one Texan hospital used it in the clean-up after an Ebola case.

More than 500 healthcare facilities, mostly in the US, have the machine. In California and Nebraska, it has already been put to use sanitising hospital rooms where coronavirus patients received treatment, the manufacturer says.

In China, where the outbreak began, there has been an adoption of new technology to help fight the disease.

The nation is already the highest spender on drones and robotics systems, according to a report from global research firm IDC.

Leon Xiao, Senior Research Manager at IDC China says robots have been used for a range of tasks, primarily disinfection, deliveries of drugs, medical devices and waste removal, and temperature-checking.

'I think this is a breakthrough for greater use of robotics both for hospitals and other public places," says Mr Xiao. However space in hospitals to deploy robots and acceptance by staff are challenges, he says.

YouiBot has quickly developed its own disinfecting robot

The coronavirus has spurred home-grown Chinese robotics companies to innovate.

Shenzhen-based YouiBot was already making autonomous robots, and quickly adapted its technology to make a disinfection device.

"We're trying to do something [to help], like every one here in China," says YouiBot's Keyman Guan.

The startup adapted its existing robotic base and software, adding thermal cameras and UV-C emitting bulbs.

"For us technically, [it's] not as difficult as you imagine… actually it's just like Lego," says Mr Guan.

YouiBot at a hospital in Wuhan

It has supplied factories, offices and an airport, and a hospital in Wuhan. "It's running right now in the luggage hall… checking body temperature in the day, and it goes virus killing during the night," he says. However the robot's efficacy hasn't yet been evaluated.

Meanwhile plant closures and other restrictions to curb coronavirus, have hampered getting parts. "The lack of one single component, [and] we cannot build a thing," adds Mr Guan, though he notes things have improved in the last couple of weeks.

"There are not many good things to say about epidemics," says Professor Kolmus, but it has forced industry "to find new solutions".