The Fed's four radical moves to save the economy

- Published

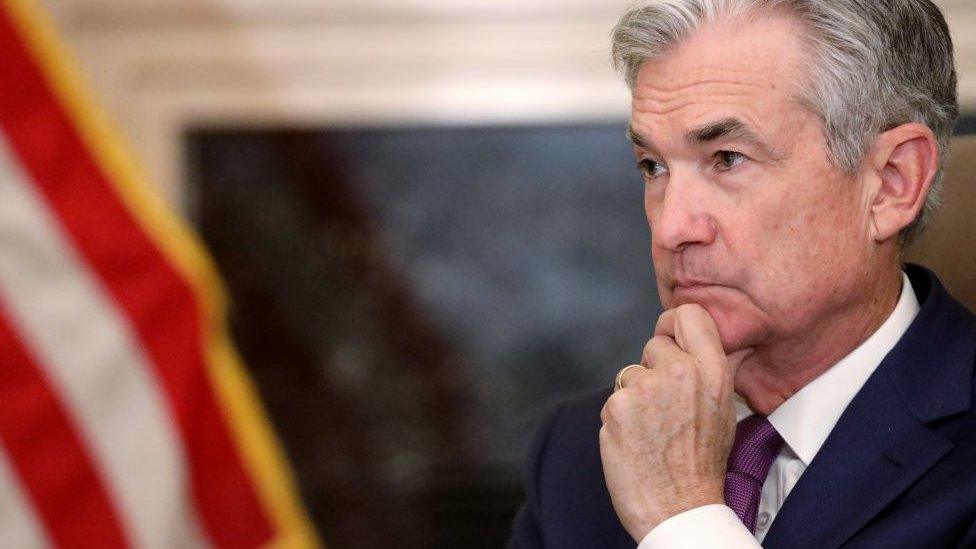

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell is grappling with the worst economic crisis since the 1930

As policymakers from America's central bank prepare to meet - virtually - this week, they will be looking to see if the extraordinary steps they have taken to confront the world's most severe economic crisis since the Great Depression are working.

Since March, the Federal Reserve has pledged to pump more than $4tn (£3.2tn) into the financial system, slashing interest rates, relaxing banking rules, and dramatically expanding its lending.

The Fed's moves, which have increased its balance sheet by more than $2.2tn so far, have been replicated to some degree by many other central banks, including the Bank of England.

The responses, which typically complement massive new government spending packages, are an effort to keep money flowing despite the near-freeze on business activity during the pandemic.

"They've taken basically what they did in the global financial crisis and now it's on steroids," says Frederic Mishkin, a professor of banking and financial institutions at Columbia Business School.

1. The Fed rushed dollars to foreign countries and financial firms

The financial system was under strain this spring, as investors pulled funds out of a collapsing stock market, companies tapped credit lines in anticipation of lockdown losses and people in other countries looked to hold dollars for stability.

Responding to the rush, the Fed used emergency powers to advance funds to major financial institutions. It also made it easier for foreign central banks to exchange their own currencies for dollars through so-called "swap lines".

The Fed was able to respond quickly, since it had developed the programmes during the 2007-2009 financial crisis, says Alan Blinder, professor of economics and public affairs at Princeton University. But at that time, the Fed was trying to shield the wider economy from risky bank behaviour, whereas now the Fed is working to protect the financial system from the bigger economic crisis.

"That's not because they care about the bankers," Prof Blinder says. "It's because if the financial system started to implode, which it had started to do, that's going to reverberate back onto the real economy and make things that much worse."

The Fed will offer loans to companies outside of the financial sector

2. The Fed offered to buy debt from big companies

But the Fed has gone beyond simply shoring up the financial system.

Fearing a wave of bankruptcies, as shutdowns create holes in company budgets and worried banks refuse to lend, the Fed in March said it would work directly with big companies on loans and bond offerings. It pledged up to $100bn to the effort, and within weeks had expanded its potential commitment to $750bn.

It has also said it would buy up to $100bn of other kinds of debt, including credit card debt, car financing loans, student loans, commercial mortgages and "leveraged" loans. The list is so extensive, some financial industry commentators on Twitter joked the bank would be buying baseball cards next.

The US Treasury is backing the programmes with $85bn - a sign that unlike most of its actions in 2008, the Fed is worried about losses.

Others have warned the bank's actions could encourage future risky borrowing. "Markets work best when participants have a healthy fear of loss," Oaktree Capital Management co-founder Howard Marks wrote. "It shouldn't be the role of the Fed or the government to eradicate it."

Many economists say those kinds of fears are overblown, given the unique nature of the current coronavirus-triggered crisis - which has created cash-flow problems even for firms on a solid financial footing.

"I think this is such a large external shock, that I think it is appropriate for the central bank to come in to provide liquidity and try to prevent some of the costs [to society]," says economist Nellie Liang, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a former director of financial stability at the Fed.

Businesses have overwhelmed America's rescue programme

3. The Fed is also lending to small businesses directly

The Fed has announced it would launch its own "Main Street" lending operation, dedicating up to $600bn to fund low-cost four-year loans worth $1m-$25m for mid-sized firms - something it has never done before. The Treasury Department has put $75bn to the plans, which were announced after the government's small business aid programme was overwhelmed by demand.

"It's a big step for the Fed, but I think this crisis is unusual," says Ms Liang. "The issues are not just market liquidity they're also liquidity for smaller firms that don't often have access to the market so to the extent that the Fed can provide some support here, it seems important."

But, she adds: "The Fed has to think really carefully about how to design the Main Street programme to help borrowers and not just increase their debt load."

Indeed, many of the current economic problems can't be solved by lending, Prof Blinder warns, pointing to the need for the government to increase spending on items like healthcare and unemployment benefits.

"Will these activities help the economy weather the storm? The answer is yes, but the operative word in that sentence is help - the Fed cannot do this by itself," he says.

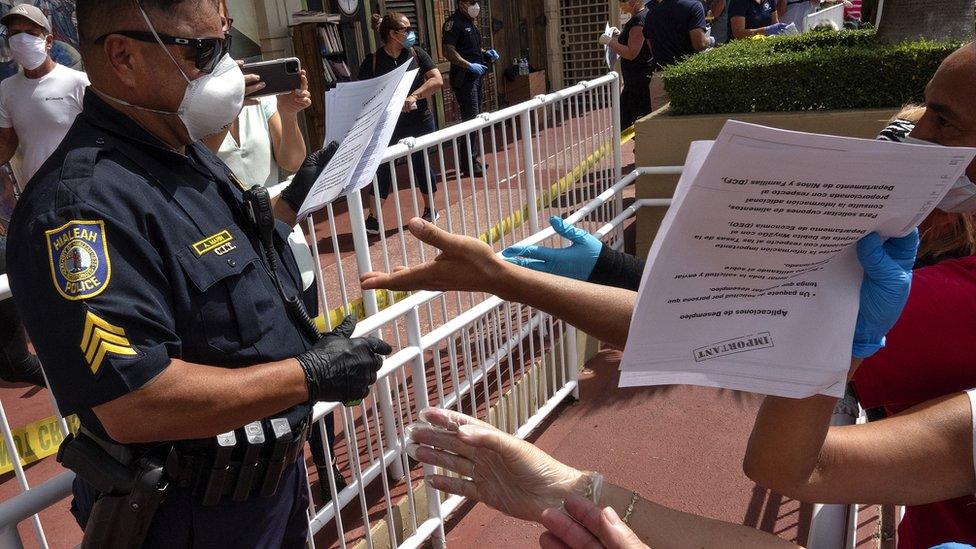

A police officer hands out unemployment benefit applications in a car park in Florida

4. The Fed is also helping local governments.

The increased costs of healthcare and social programmes, combined with plunging tax revenue, have created huge problems for local governments. Ordinarily, they could borrow money by issuing bonds. But that market seized up earlier this year, as the enormity of the crisis made investors wary about repayment.

So, the Fed said it would buy up to $500bn in new bonds issued by states, cities and counties of a certain size - something else it has never done before. The Treasury Department is backing the effort with $35bn.

The Fed's promise alone has appeared to re-set demand and help bring down the cost of borrowing, says Michael Belsky, executive director of the Center for Municipal Finance at Chicago University's Harris School of Public Policy. "This is a godsend," he says. "For the most part, I think it's a very creative and appropriate thing to be doing."

But the Fed must guard against creating the expectation that it will be there to backstop cash-strapped local governments in the future, encouraging imbalanced budgets even in ordinary times, says Frederic Mishkin, professor of banking and financial institutions at Columbia Business School.

"Although providing fiscal stimulus was the right thing to do, they've got to make very clear how unusual this is," he says.

After all, the Fed has had difficulty dialling back its activity after the 2008 financial crisis. While many hope the current economic shock will be short-lived, the powers the Fed has assumed may well prove long-lasting.

- Published1 December 2017

- Published17 April 2020

- Published23 April 2020