Stressed firms look for better ways to source products

- Published

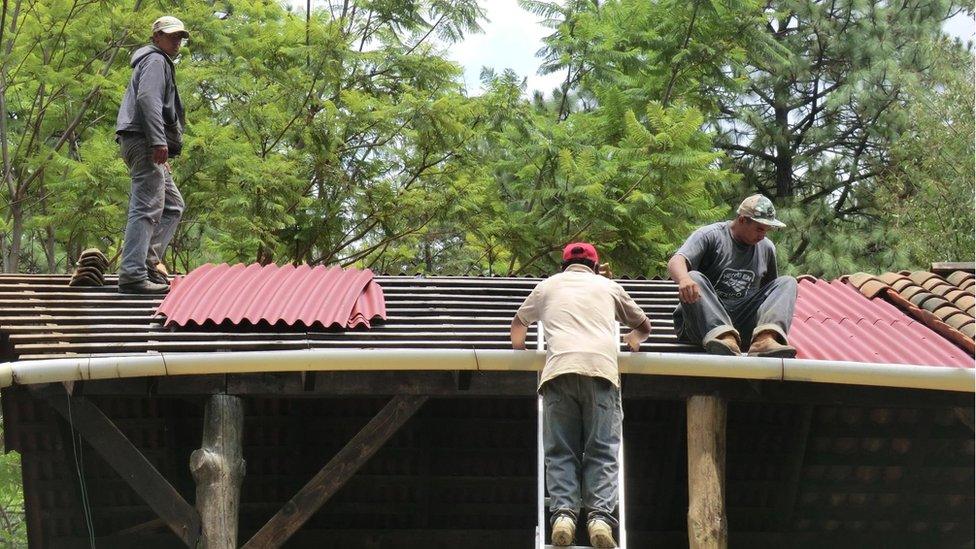

Onduline products are sold in more than 100 countries

Maxime Firth's business is complicated to manage, even in good times.

His company, Onduline, turns recycled fibres into roofing material, after dousing them with bitumen to make them waterproof, and sells products in 100 countries.

Its eight production plants span from Nizhny Novgorod in Russia and Penang in Malaysia, to Juiz de Fora in Brazil.

Further complicating his supply chain, Mr Firth's business is strongly seasonal. People install roofs in the summer, so products are made from January to March, to sell from April to September.

The big question for him is how much demand there will be from important markets like China and the US.

"Instead of manufacturing something that you are forced to sell, it is better to know what the market wants to buy," he says.

The impact of coronavirus makes it difficult for businessmen like him to make the right decisions.

To manage demand Mr Firth's company used to work with "homemade" IT tools mainly based on Excel spreadsheets.

But now he is using software accessible over the internet (also known as cloud-based) which can model his situation every week.

It allows the firm to use the latest data to explore how demand might start returning in different markets.

"In terms of profitability, and also production, it's changing every week," he says.

Coronavirus "puts supply chain planning under the spotlight," says Frank Calderoni, chief executive of Anaplan, whose software Onduline has been using.

Some companies have seen sales dry up: like Mr Firth's roofing material purchases, which he says are down 70%.

But demand for some goods has rocketed, including groceries, books, coffee, and toys for children.

Supply chain chaos could last at least another 18 months, and probably longer, says Len Pannett, president of the UK roundtable of the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals.

Supply chain disruption could last another 18 months experts say

Businesses trying to get back to work may find their overseas suppliers are still in lockdown.

The more information available about every firm in the chain, the better.

"Being in touch with a customer's customer's customer, you can see ahead of time what's coming your way" and start finding alternative suppliers if you need to, Mr Pannett says.

Most businesses had been monitoring supply chains, finance, and sales with different tools.

Joining these silos into one cloud platform lets finance teams peek into supply chains and sales, and be more efficient with money, he says.

And with margins tighter than ever, businesses will need to make better decisions.

More accurate real-time information will help them do this, and keep better track of their decisions' effects, according to Mr Calderoni.

Supply chains were already trickling onto the cloud and he says coronavirus will accelerate that move, with technologies like blockchain and artificial intelligence (AI) becoming commonplace.

Susan Hunter looks after the day-to-day operations of Khalifa Bin Salman Port

For the Gulf state of Bahrain - an island - all its ventilators, facemasks, medicines, and 99.5% of the goods in its market come through its only port.

The outbreak forced the port to change its procedures, says Susan Hunter, who as head of APM Terminals Bahrain is in charge of Khalifa Bin Salman Port's day-to-day running.

The port had to quickly arrange for lorry drivers to apply for gate passes, do security checks, and make payments online.

It has also set up a critical cargo programme, to identify containers carrying medical supplies, to allow these to swiftly pass these through customs and put them where they can be accessed quickly.

Ms Hunter would like to move all the administration to a blockchain system. "There's no resistance, just 'How are we going to make that happen?'" she says.

"We're just a couple of steps away from being able to put a lot of our documents onto a blockchain platform, we are seeing the industry changing that way," she says.

Blockchain keeps a record of transactions in a ledger, stored across a number of computers linked in a peer-to-peer network.

This lets firms share information about a container just once, but everyone up and down the chain can see that information.

It allows "the right person to have the right information at the right time, in a permissioned way," says Richard Stockley, blockchain executive at IBM Europe.

Blockchain could make tracking goods simpler

Blockchain has made headway in areas like tracing food through a supply chain.

Walmart asked IBM to create a food tracing system based on blockchain technology.

As an experiment, Walmart's chief executive pulled out a packet of mangoes, imagined they were toxic and asked how long it would take to find out where they came from, and where the other mangoes in that shipment were.

Manually, it took six-and-a-half days to find the answer. But using blockchain "we've got that down to about two seconds," says Mr Stockley.

The biggest challenge in introducing blockchain to supply chains is getting different organisations to collaborate.

"Blockchain is a team sport," he quips.

But Mr Stockley says blockchain can make supply chains "a lot more resilient, more transparent, and proactive," and will get much more attention as we emerge from coronavirus.

Amazon has changed forever how quickly we expect products to arrive, and how visible their movements should be to us on the way, says Adam Compain, chief executive of San Francisco-based ClearMetal, an AI supply chains startup.

But outside Jeff Bezos's company, big corporate supply chains are still pretty static.

Typically, every six months, a company will look at how long it takes products to go from China to a warehouse and on to a store shelf, he says.

Companies would like to know exactly where their products are

Getting more up-to-date information means making sense of thousands of pieces of information each day about where products are.

Much of that information can be poor or conflicting. For example, a delivery company might tell you twice that the same shipment has been delivered, or is out for delivery.

But machine learning algorithms can spot patterns in this messy data. Maybe the same delivery company always sends two messages, but the first is generally more accurate.

AI is now much better than humans at spotting whether there's a storm brewing now that will delay your shipping container next week, Mr Pannett says.

For thousands of businesses like Mr Firth's in France, the coming year will be tough.

"Now we know until May we are okay," he says. After that, "we don't know if the customers will pay us."

So each week his company, like many others, will make high-stakes decisions using a combination of luck and the best tools technology can offer.

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

LOOK-UP TOOL: Check cases in your area

MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash