The stealthy little drones that fly like insects

- Published

Engineers admire the dragonfly's flying ability, but have found it impossible to mimic

When Storm Ciara swept across the UK in February, Alex Caccia was strolling on Oxford's Port Meadow watching birds take to the air.

He marvelled at their indifference to high winds: "While airliners were grounded by the weather the birds couldn't care less!"

It was more than just a passing thought for Mr Caccia, who is the chief executive of Animal Dynamics, a technology start-up applying lessons from wildlife to drone design.

Formed in 2015 to pursue the science known as biomechanics, his company already has two drones to show for an intimate study of bird and insect life.

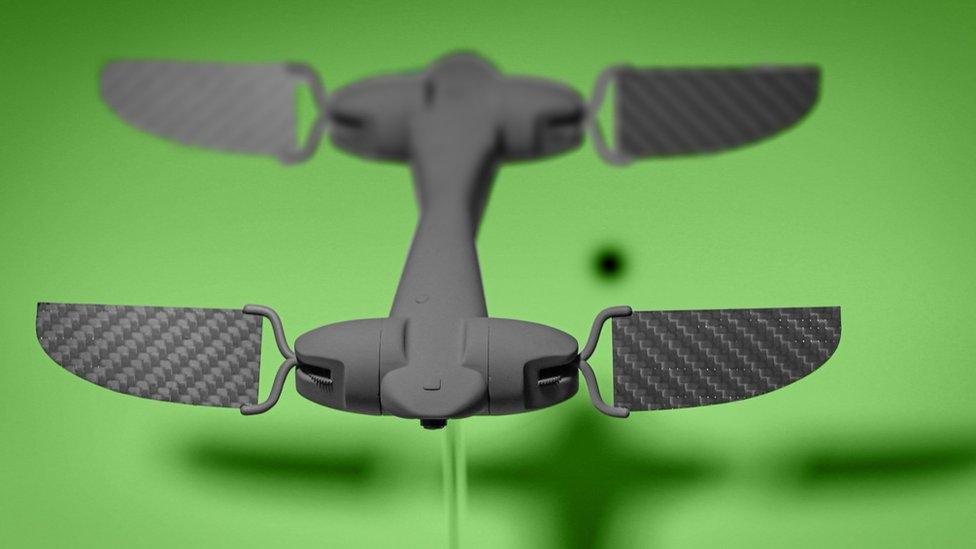

One takes inspiration from a dragonfly, and has attracted funding from the military. Its four wings make it steady in high winds that would defeat existing miniature spy drones.

Known as Skeeter, the secretive project has cracked the challenge of using flapping wings to power a drone. While wings are more efficient than a propeller and allow a dragonfly to hover in the face of strong gusts they are almost impossible for human engineers to emulate.

Alex Caccia with a prototype of the Skeeter drone

"Making devices with flapping wings is very, very hard" says Mr Caccia. Helicopters manoeuvre by changing the pitch of rotor blades to go forward and backward or to hover. For smaller objects hovering is a major challenge.

"A dragonfly is an awesome flyer" says Alex Caccia, "It's just insane how beautiful they are, nothing is left to chance in that design. It has very sophisticated flight control."

The dragonfly does have 300 million years of evolution on its side. Animal Dynamics has spent four years writing software that operates the hand-launched drone like an insect and allows it to hover in gusts of more than 20 knots (23mph or 37km/h). From 22 to 27 knots is classed as a "strong breeze".

That software gives Skeeter a degree of autonomy and guides it around obstacles towards its objective.

And it meets a Ministry of Defence desire for a wind tolerant miniature reconnaissance drone to let soldiers spy on threats concealed ahead.

The Skeeter can hover in winds of 20 knots

Skeeter will carry a camera and communications links into the skies and should be cheap enough for operators to lose some without denting the defence budget.

It is currently around eight inches long, but production versions are planned to be smaller. Squeezing a lot of aerodynamic and navigational wisdom into a diminutive package is nature's prerogative but was a big challenge for Animal Dynamics. "We started small to learn hard lessons" as Alex Caccia puts it.

Animal Dynamics's 70-strong team relied on electronics from the smartphone industry to shrink their knowledge into Skeeter's frame. Insights into robotics, biology and software all play their part in the design but mobile phones have been a boon to all mini-drone makers.

Guido de Croon and the Delfly

Guido de Croon, a Professor at Delft University of Technology (TU Delft), acknowledges the debt bio-mechanics pioneers owe to smartphones. His team has built a series of flapping wing drones which rely on mass-produced digital components. "I am very happy with the mobile phone industry," he says.

Under the family name of DelFly, the creation from TU Delft weighs less than 50g, and takes inspiration from the wing movement of fruit flies. DelFly's four wings consist of an ultra-light transparent foil powered by a light, economical motor, which lets it fly for six to nine minutes.

The wings might look delicate, but they can touch a surface or even fly into an obstacle and the DelFly will right itself like an insect hitting a window. For most existing drones with rapidly spinning propellers, such a contact would be disastrous.

Smartphone camera lenses feed vision back to AI software and Mr de Croon is developing algorithms that mimic the avoidance senses of an insect.

WATCH: Could bots swarm in to rescue you one day?

The DelFly team's goal is to achieve autonomous flight indoors, useful for roles such as monitoring crops inside large greenhouses. Mr de Croon reckons that one day bio-mechanics could tailor a drone for each and every purpose. "Each task has its own ideal drone."

At Animal Dynamics the Stork, Skeeter's much bigger and more public sibling, was inspired by similarities between light parasail wings and large birds. Stork is built to take knocks and suffer the attentions of clumsy operators.

Constructed around a tubular metal frame that is easy to repair it uses an electric engine pushing a rearwards-facing propeller and has a collapsible parasail for a wing.

Controlled remotely via GPS signals Stork's brain consists of a black box spouting two little mushrooms that are antennae for the navigation system.

The current version has a shoebox-sized payload bay but a larger model could be launched in flocks to distribute food or medical supplies across inhospitable terrain in Africa or Latin America. The nylon parasail folds into a bag and lifts itself as the Stork's engine putters along any vaguely flat surface.

The Stork looks like a flying baby buggy

The machine lands almost vertically so can reach just about any spot. The remote operation via GPS allows it to be flown back to a central point once the cargo bay has been opened and emptied.

With its pram tyres and near-unbreakable frame Stork is a utilitarian machine. The designers call it a flying mule and that prompts Alex Caccia to perform his party piece, seizing a Stork resting on a work surface and hurling it onto the floor where it sits undamaged and electronically unperturbed.

Stork may be shipped out in parts and assembled locally by operators in locations where medical support drones are needed..

As an alternative to 4X4s or motorbikes the Stork's marriage of easily-mastered technology and rugged design stands out in a world where delivery drone design has been distracted by efforts to fly parcels to urban consumers.

Bio-mechanics takes a contrasting approach to that of most drone designers courtesy of dragonflies, storks, fruit flies and of course, mules.