The perfume makers that can't smell a thing

- Published

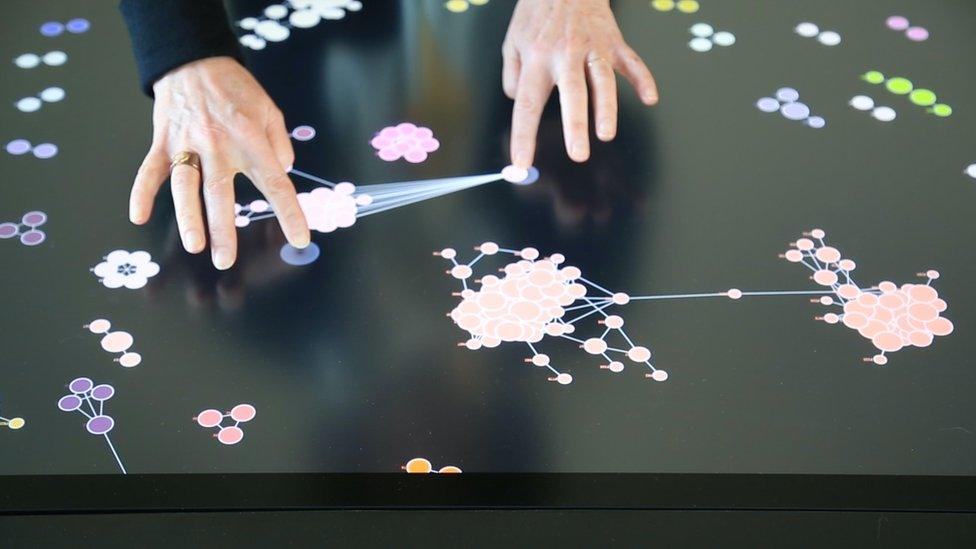

The Carto system can store 1,500 ingredients

Do you need a human to create a beautiful scent? That's the question being asked as artificial intelligence (AI) starts to infiltrate the perfume industry.

Companies are increasingly turning to technology in order to create more bestselling, unique fragrances that can be produced in just minutes.

Last year, Swiss-based fragrance developer Givaudan Fragrances launched Carto, an artificial Intelligence-powered tool to help perfumers.

Through machine learning (a way computers improve outcomes automatically by learning from past results) Carto can suggest combinations of ingredients.

Using a touch screen, the perfumer can pull together different scents using data from the brand's vast library of fragrance formulas - a much more efficient process than using spreadsheets. A small robot immediately processes the fragrances into perfumes, making it easier for perfumers to test their new scents.

"It's about finding a way to give more time to the perfumer," says Calice Becker, vice president perfumer and director of the Givaudan Perfumery School.

"The perfumers can choose from 1,500 ingredients and put it in a bottle without touching the ingredients. It helps to make sure you don't lose time and have to look at your notebooks."

The Carto systems can create fragrances very quickly

Ms Becker says the process of perfumery has evolved over the years and this is just the next step.

"Up until about 40 years ago, perfumers worked with all the ingredients in front of them and they'd grab the ingredients and write down the amounts and names of ingredients on a piece of paper."

The 1980s saw the introduction of computers and perfumers would create their concoctions through a system that looked like an Excel spreadsheet, she says.

One benefit of Carto is that samples are created instantly, giving them a competitive advantage. "We can adjust the perfume almost live with the customer," says Ms Becker.

"It is a big plus not just because we gain time but there's more intimacy when we connect in front of the tool."

What has been their customer's reaction? "We have some early adopters but some say they will never use it," she says. "I think that's totally normal. But it's created a lot of buzz from customers interested to see how they can see creations with it."

AI is not designed to replace perfumers

German fragrance house Symrise has gone one step further and teamed up with IBM Research to create an AI called Philyra, named after the Greek goddess of perfume, that actually studies the aromatic formulas and customer data to produce new fragrances.

Philyra was taught in a similar way to an apprentice perfumer, who can study for 10 years before making good new scents.

Like Carto, Philyra can't actually sniff anything.

Instead, families of smells, including florals, orientals and chypre, were coded along with the different requirements of products like shampoos, deodorants and skin lotions.

The AI was also taught about how much of each ingredient would be appropriate.

Claire Viola, vice president of digital strategy fragrance at Symrise, is the first to agree it hasn't been without flaws.

"It's machine-learning and sometimes the results have been wrong," she says. "It's still a project, the more we test, the more it continues to improve. It constantly needs training. You have to qualify every new material, so it understands the difference between different florals and oriental scents, for example."

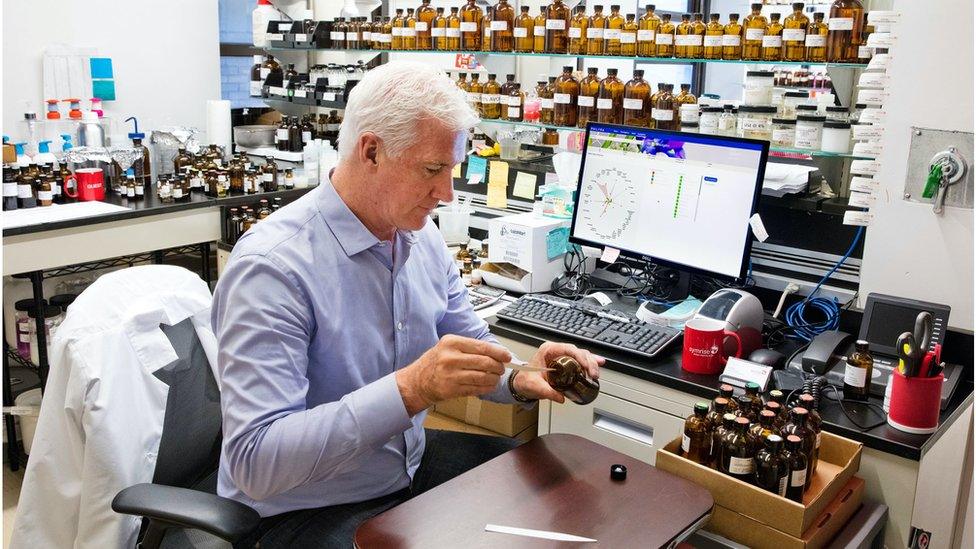

Philyra: It "never forgets" but still needs training, says Claire Viola

But, she says, the more they invest in training, the more accurate it becomes.

"We taught it to be like a perfumer... the machine never forgets [compared to humans]. The good thing is that the machine comes up with a selection of scents and interesting combinations that you wouldn't have thought of."

Given that the machine has a database of close to two million aroma formulas - the potential for a wider range of scents and combinations is huge. In 2019 Brazilian cosmetics company O Boticário worked with Symrise to launch the first fragrance using artificial intelligence.

One company is shaking up the sector by giving consumers the opportunity to play with the technology directly.

In Breda in the Netherlands, ScenTronix allows customers to create their own personalised scent based on a questionnaire they answer when they walk into its Algorithmic Perfumery shop.

After answering questions such as how do you see your role in life and what kind of environment did you go grow up in, the algorithm analyses the data to create unique perfumes for the customer within seven minutes. Customers can buy five samples for €30 ($33; £26).

Frederik Duerinck wants to move customers away from brand names

ScenTronix co-founder Frederik Duerinck says he wanted people to be able to wear a perfume that was a reflection of themselves in that current moment.

"The perfume industry is a lot about branding and adapting your identity to it," he explains. "I thought it would be a good idea to completely change the dynamic and and so the perfume becomes about who you are and not about the brand."

Mr Duerinck agrees there is a major physiological barrier to overcome as people aren't used to paying for a fragrance they're unable to test until it's been produced.

However, he says they try to overcome that hurdle by having someone on site to help customers. "Although I'd say 75% of the time it is spot on, we always have a professional there [to help]," he says.

Scentronix machines mix the perfume

Margaux Caron, global beauty analyst for colour cosmetics and fragrance at Mintel, believes artificial intelligence is a powerful tool to create fragrances that are original.

"Not only do they [AI tools] identify olfactory white spaces but they also dramatically optimise the speed of fragrance creation for perfumers.

"Technology and science are sometimes pictured and perceived as cold and rational, but the fragrance category is displaying a warm, emotional, human approach to it. The partnership between AI and perfumers is anchored in this philosophy."

The personalised scent

So does the introduction of technology spell the end of the perfumer? Not according to those I spoke to.

"It will never stop the role of the perfumer," says Ms Becker. "The computer will never come up with beautiful ideas. But it can help bring them alive."

Ms Viola agrees, adding that it's complementary support to their work, allowing them to experiment much more.

"It's not replacing the perfumer," she says. "It's helping them to be better faster and creative and freeing them from boring tasks. It still starts and ends with the perfumer. They're the ones with the intuition, emotion and feeling and guiding the machine to better results."

For now at least, as Ms Viola says, "It's a man-machine collaboration."