Broadway workers fight to stay afloat with theatres closed

- Published

After waiting for years to have her own chair in a Broadway orchestra, Katie Kresek's show was closed in March

Violinist Katie Kresek waited for more than a decade to have her own chair in a Broadway orchestra.

Last year, she became the co-orchestrator and violinist for the theatre performance of Moulin Rouge! the Musical. Just 10 months after she started, the lights seemed to go down on her dream.

She says she'll be "heartbroken" if the show doesn't return. "It's sad that when it finally happens, it has to be cut short," she says.

Instead of performing eight shows a week for a live audience, Kresek now records music alone in her bedroom.

Her story is a familiar one to other live performers and particularly Broadway's thousands of workers.

Katie Kresek (left) performing before the coronavirus pandemic

On 12 March, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo ordered Broadway's 41 theatres to close as the coronavirus pandemic spread through the city. The shows, with their hundreds of closely packed seats, presented a high risk for Covid-19 to spread among the audience.

In June, the industry announced that closures would extend until January next year.

Holly Coombs, the production stage manager for Mean Girls - the musical adaption of the film by the same name - has already started looking for work outside the theatres.

She asked friends with corporate experience to help her rewrite her CV hoping to land a project management role, and she's looked for jobs at coffee shops hoping to use the barista experience she picked up in university.

Holly says when she was told the show was closing it hit her that she didn't know how she would pay her rent.

"I was in shock, I didn't have a plan."

Unemployment cheques have helped pay for her flat, but she had to tap into her saving to buy groceries and food for her dog. "We have nothing right now," she says.

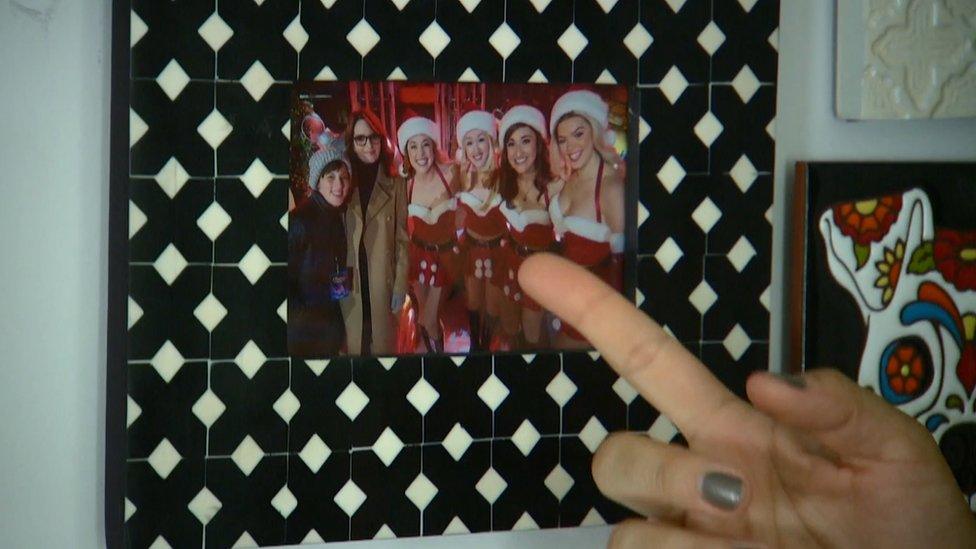

Holly Coombs has started looking for jobs outside of Broadway where she can use her skills as a stage manager

Holly says she never expected to be looking for a career change in her 30s. Proudly hanging on her sitting room wall among pictures of family and close friends is a photograph of the show's four leading actors and its writer, the comedian Tina Fey. She describes them as her "Mean Girls family".

"We spend so much time in the theatre together it's really taking away a huge chunk of our life," she says.

But, like so many others during the coronavirus pandemic, she is having to rethink how her life might play out.

Stage manager Holly Coombs points to a picture of her "Mean Girls family"

Broadway supports more than 96,000 jobs in New York and contributed nearly $15bn (£11.2bn) to the city's economy in 2019, according to the Broadway League, external, a theatre union. That number does not just take into account ticket sales but also the investment to put on and run a show, and the money tourists spend when they come to New York to see a performance.

Without Broadway performances, many businesses in the city's midtown area surrounding the theatres are also suffering.

One of the biggest fears of both Broadway workers and local businesses is that shows will not return at all. Already Disney's Broadway version of Frozen and the Broadway revival of Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? have said they will not be reopening when the coronavirus measures are lifted.

Broadway theatres, closed since March, aren't set to open until next year - leaving thousands of workers in limbo

But for Broadway veterans, nothing will ever replace live performance.

Judy Kuhn has starred in shows including Les Misérables, Fiddler on the Roof and Chess. Her performances as Helen in the Broadway production of Fun Home earned her one of her four Tony nominations.

That might be why she finds it so frustrating to hear friends ask whether theatre has just moved online during the pandemic. She tells them no, "that's just TV".

"TV is great, but that is an experience the audience has alone," she says.

"The thing that is so unique about live performance is it happens once that particular night with that particular audience and those particular performers."

Judy Kuhn (right) playing Helen in the Broadway production of Fun Home. Her performance earned her a 2015 Tony nomination

Judy was just two weeks into rehearsals for an off-Broadway performance of Assassins when New York went into lockdown.

Since she has been unable to work she has joined in a number of internet performances. Actors and musicians from several past and present shows have come together either via live stream or taped video calls to sing or re-enact scenes from their homes.

But there is an obvious drawback for actors and musicians, she explains.

"I haven't been paid for any of the online performances I've done and I don't know of anyone who has profited from them," she says.

Over the last several years ticket prices for Broadway shows have skyrocketed. The average ticket was $145 (£110) for the 2018-19 season.

With the coronavirus recession tightening families' spending habits, online performances may become the way more audiences choose to engage with theatre.

But money will not be the only thing that potentially keeps audiences away. While many shows are set to resume next winter another surge in Covid-19 cases could push that date back, leaving Broadway's thousands of workers in limbo and its theatres dark.

- Published17 June 2020

- Published27 July 2020