Trump taxes: A 'fundamentally unfair' system?

- Published

For years, US President Donald Trump has shrugged off criticism of his low tax bills, famously boasting that not paying taxes made him "smart".

"Like every other private person, unless they're stupid, they go through the laws, and that's what it is," he said during last month's presidential debate, when confronted over the New York Times report that he had paid just $750 in income taxes to the federal government in 2016 and 2017, and for 10 years, paid nothing at all.

So how unusual is his tale?

In the US, Mr Trump's route to such low sums, using business losses and expenses such as haircuts to offset other gains, has raised legal questions, triggering investigations by tax officials and authorities in New York.

And in other countries, Mr Trump might find it harder to deploy such strategies so freely, says Andy Summers, professor of law at the London School of Economics.

The UK, for example, has rules that limit how much losses in one business can be used to offset gains elsewhere.

All that suggests Mr Trump is a special case, notwithstanding research finding higher rates of tax avoidance among the super-rich.

But in other ways, tax experts say, Mr Trump has a point. Many of the world's wealthy pay less than what official tax rates might imply - with no need to resort to tricky tactics at all.

Donald Trump's refusal to release his taxes has been a source of political controversy

"It's not, 'Oh there's one person who's doing it,'" says Arun Advani, a professor of economics at Warwick University, who has examined taxes in the UK. "It's actually a relatively common experience."

Wage earnings hit harder

In the UK, a quarter of those earning between £5m and £10m in income and capital gains paid an effective average tax rate of just 11%, Prof Advani and Prof Summer found looking at recent tax data, external. That was not just lower than the official top income tax rate of 47%, but lower than the rate charged on someone earning just £15,000.

In the US, the 400 richest American billionaires paid an average overall tax rate of 23% in 2018 - lower than the 24% rate paid by the bottom half of households, economists at the University of California - Berkeley estimated, external in a 2019 paper.

The difference between the headline rates and what governments actually collected was driven by laws that hit wages and salaries with higher tax rates than other types of income, such as property and stock market investments, which belong disproportionately to the rich.

Morris Pearl says how much tax he pays has nothing to do with his real gains

Former New York banker Morris Pearl, 60, who has described his fortune as in the "tens of millions", says his federal income tax rate is in the high teens - far lower than America's official rate on top earners of 37%. That's despite strong gains in recent years in his stock market investments, which he has relied on for income since retiring from his job at investment giant Blackrock in 2013.

"The whole system is so fundamentally unfair," says Mr Pearl, now chairman of the Patriotic Millionaires, a group of wealthy Americans that backs higher taxes on the rich. "How much tax I pay has absolutely nothing to do with how much money any normal person would say I made."

Inequality driver?

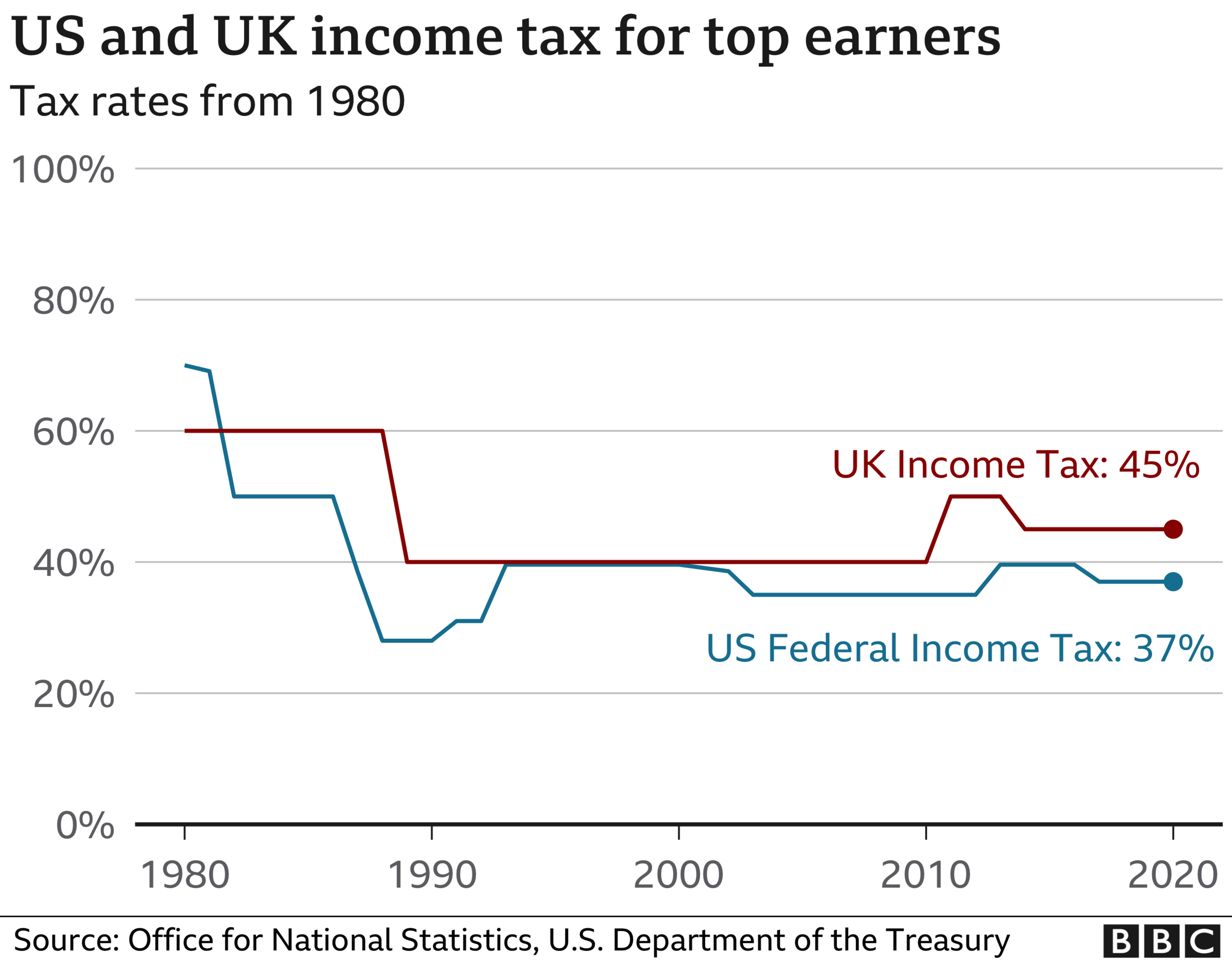

Since the 1980s, official tax rates on top earners have generally fallen in developed countries, never recovering from the cuts ushered in during the rightward political turn that swept global policy circles during the Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher era. While some countries have shifted the income level at which the top rate kicks in, or raised rates following the global financial crisis, the overall downward trend remains.

And most countries - even famously high-tax Denmark - have opted to reward investments and property with lower tax rates.

Advocates of the policies say they encourage investment, helping to spur growth and job creation. And they note that the rich still account for a disproportionate share of income collected by the government.

But it's a set-up that is increasingly being blamed for fuelling inequality and political instability.

Danish millionaire Djaffar Shalchi has founded Human Act, which campaigns for raising taxes on the wealthy among other things

Last summer, Mr Pearl helped to organise a letter from some of the world's richest, urging governments to raise taxes on the wealthy to help pay for the coronavirus pandemic.

Their cry has helped to drive political debates in the US, UK and elsewhere.

Another organiser of the letter, Djaffar Shalchi, a property and construction magnate in Denmark, says even his famously progressive country has seen its tax code become less so over time. He wants to see it reinstate a wealth tax to address the disparities.

"If we are not going to address this problem, then we will have the US system, maybe in 20 years," he says. "We are going in that direction."

Buckinghamshire tech entrepreneur Gemma McGough, who describes her fortune as "less than £20m", was one of the letter's UK millionaire signatories.

Buckinghamshire millionaire Gemma McGough estimates her family paid a roughly 40% tax rate

Ms McGough says she paid a roughly 40% rate last year, on income made primarily from savings and investments.

But when she and her husband sold their first business, Product Compliance Specialists, in 2014, they benefited from UK tax relief for entrepreneurs, which until recently shielded them from some taxes up to £10m in gains from certain business sales.

"I feel quite guilty about having become so wealthy," Ms McGough says. "I didn't feel that way during any of the time that I was running the business... because I felt like it was really hard work.

"It was only later, after we sold that it was like, 'No, there's a lot of people working really long hours,' and most people are not millionaires at the end of it."

Tax policy shift?

Ms McGough, Mr Pearl and Mr Shalchi remain a minority among their class - fighting against the tide of recent policy changes.

The UK cut the top rate on earners in 2013, reversing a rise from just a few years earlier, while the US cut tax rates on the top as recently as 2017.

But since Patriotic Millionaires was founded in 2010, its general aims have won some high-profile endorsements, including from investor Warren Buffett, who called for raising taxes on the rich in 2016, famously noting that his 16% federal income tax rate was lower than his secretary's.

Mr Pearl, whose recent tax payments of nearly $100,000 were still far higher than Mr Trump's, says he's hopeful that outrage over stories like Mr Trump's will force the pendulum of tax policy to start swinging in the other direction.

"It was kind of very abstract before but I think... people are realising that most people are paying a much higher share than some of our wealthiest citizens," he says. "A lot of people have decided that's not fair."

- Published20 October 2019

- Published13 July 2020

- Published29 September 2020