Will cruise ships return to Venice?

- Published

"Work! Work! Work!" shout the baggage handlers, ship cleaners and port security guards protesting on the steps of Venice's Santa Lucia train station.

The protest formed quickly and without warning - a flash mob, designed to call urgent attention to the 6,000 Venetians who rely on the cruise industry for work. After 15 minutes they are gone.

This year, international travel restrictions caused by the coronavirus are forcing cruise companies to delay most tours until 2021.

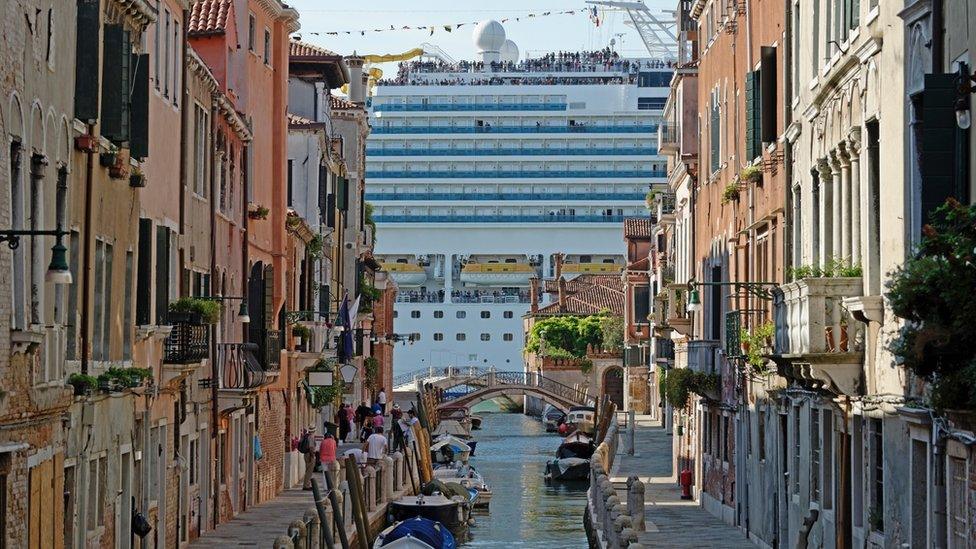

That's meant the ships that usually tower high above Venice's historic bell towers and basilicas have been noticeably absent.

Environmental campaigners have welcomed the change. They've been calling for cruise ships to be banned from Venice for years because of concerns about pollution and continual damage to the fragile foundations of the city.

Traditionally known as La Serenissima, Venice is no longer "'the most serene" but rather one of the most polluted ports in Europe, according to the green campaign group Transport and Environment.

Supporters of the cruise industry say the Italian government in Rome must now come up with a long-term plan - such as a new cruise terminal, outside the Venice lagoon - that will protect the city, but also guarantee the ships' future in the area.

Cruise industry workers calling for an "immediate solution for Venice's home port"

Antonio Valecca is a porter with the baggage company Portabagagli del Porto di Venezia, which has been transporting tourists' luggage from ships to Venice's hotels for the past 80 years.

"When the coronavirus is finished, we need to bring the cruise ships back to Venice," he says. "This is the moment for the government to make a decision."

Because of the continuing debate, the world's second-largest cruise firm, Royal Caribbean, has already announced that next summer, its cruise liners won't be calling at Venice.

Instead, they will be docking at Ravenna, 150km (90 miles) to the south. Passengers who want to visit Venice will be taken there on buses.

The protesters say other cruise ships could be permanently diverted to ports at Genoa or Trieste.

"We're really worried about that," Mr Valecca says.

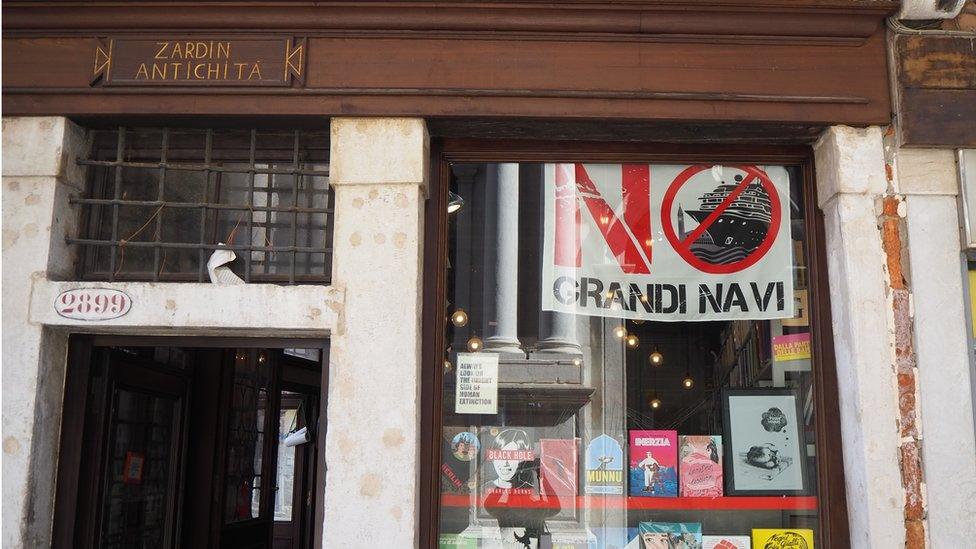

A bookshop in Venice displaying a flag reading "No big ships"

Baggage handler Vladimiro Tommasini who led the recent protest says the workers he represents are tired of waiting for the government to act.

"We are here today to protest because we've been waiting eight years for a solution regarding the passage of cruise ships in Venice," he says.

"We ask that cruise tourism has to be compatible with the structure of our city and the lagoon. We now ask for answers from the government."

Eight years ago, 33 people died when an Italian cruise ship, the Costa Concordia, capsized and sank off the coast of Tuscany after hitting an underwater reef.

The accident prompted the Italian authorities to introduce a law banning the largest cruise liners from Venice - those over 96,000 tonnes. Smaller vessels were limited to five ships per day. But the law was thrown out soon after at appeal.

Matters came to a head again last summer, when the 60,000-tonne MSC Opera lost control and crashed into a dock and a tourist boat in Venice, injuring two passengers.

The MSC Opera, its horns blaring, crashes into a boat moored at a wharf in San Basilio-Zattere

Mobile phone footage of the incident shows the ship's horn blaring as bystanders dwarfed by the 13-deck vessel shout "Get back!" and run from the incoming hull.

But despite mounting pressure, city authorities and the national government in Rome have failed to come up with a plan for the ships' future, and Venice remains divided.

Opponents of the cruise industry say the pandemic has shown what the future could look like, if the cruise liners were banned for good.

On the same day as the port workers' protest on the train station steps, a climate camp is being held in a disused industrial site in Marghera, about 20 minutes' drive across the bridge from Venice.

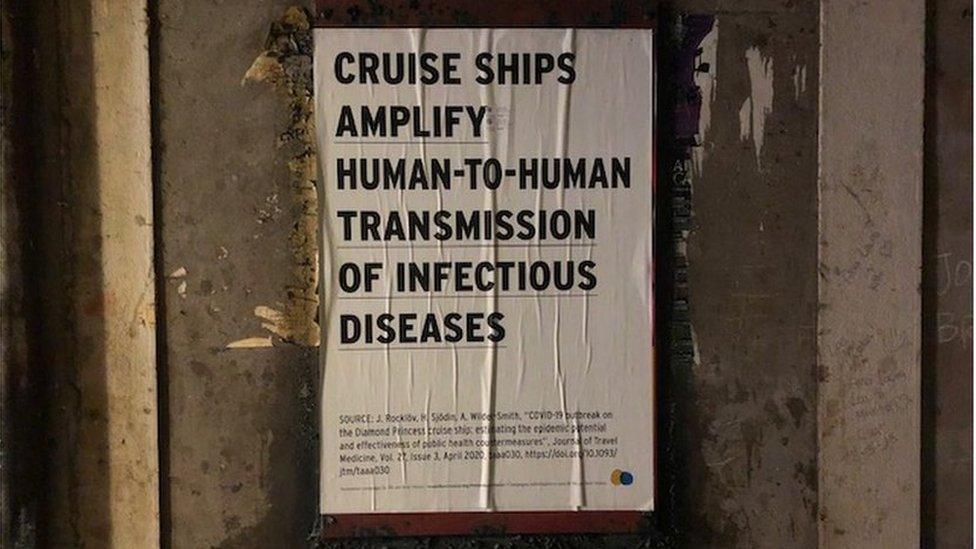

Posters linking cruise ships to the coronavirus were recently pasted on walls in Venice

Banners calling for an end to fossil fuels have been hung on the walls of a large warehouse where young people are listening to speakers making rallying calls for climate justice.

Flags painted with "no grandi navi" (no big ships) fly outside the camp.

Environmental activist Sofia Demasi is part of the No Grandi Navi committee and the international climate movement, Fridays For Future.

"Big cruise ships create a lot of pollution, a lot of problems for a city that should not be an example of the climate crisis, but of the fight against the crisis," she says.

No Grandi Navi leader Tommaso Cacciari says that as well as the pollution, the ships are damaging the city's foundations, by creating underwater waves that cause erosion.

"The stones of Venice are not concrete, they are not kept together by cement. It's kept together by mud and sand, materials that are very mobile," he says.

"And so it causes erosion of the structure of the city. And that's a big problem."

Environmental activist Sofia Demasi: "Without cruise ships Venice is a different place and we're happy"

But the environmentalists face a tough campaign against a cruise industry with powerful political allies. Italy is home to one of the world's largest shipbuilding firms, Fincantieri.

Last month, the company delivered the latest member of its fleet - a 145,000 tonne mega-ship called the Enchanted Princess, ordered by the Carnival Corporation, the world's largest cruise firm.

Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte sent his congratulations in a video message.

Carnival Corporation CEO Arnold Donald joined the ceremony by video link from Florida.

"We are facing extremely challenging times within our industry," he told the socially-distanced crowd at Fincantieri's Monfalcone shipyard.

"We thank you prime minister and your government for your ongoing support."

Carnival's 145,000 tonne Enchanted Princess, recently delivered by the Italian shipbuilder Fincantieri

Mr Donald said Carnival Corporation had been one of the largest foreign investors in the Italian economy, pointing to the €30bn ($35bn; £27bn) that Carnival has spent on Fincantieri ships over the past 30 years.

"Gathering here today helps us to focus on the joy that sailing the oceans brings to millions of guests each year," he said.

"It also reminds us of the vast numbers of people whose careers and livelihoods depend on the maritime industry."

It is not yet clear who will win the argument over the future of cruise ships in Venice, but the pressure is mounting on the authorities to reach a decision.

This year, visitors who do make it to Venice have the chance to see the city as it was, before the cruise ships came.

"If you walk near the canals now, you can see what the difference is. Without cruise ships, Venice is a different place and we're happy," says Sofia Demasi.

Additional reporting by Vera Mantengoli