Ridley Scott inspires Network Rail’s cave-exploring drone

- Published

A drone as seen in the movie Prometheus

When Hollywood director Ridley Scott filmed astronauts looking for aliens in his 2012 movie Prometheus, little did he know that it would one day inspire a Network Rail drone project.

But, bizarrely, that's exactly what has happened. Network Rail, which owns and maintains most of the railway infrastructure in Britain - from vast stretches of track to thousands of bridges, tunnels and level crossings - has long sought cheaper and easier ways of surveying the many underground caves and abandoned mines dotted around its property.

Engineers must account for "shallow" subterranean voids when doing building work or moving heavy machinery, because the caverns might collapse and cause the ground above to shift. There are more than 5,000 shallow voids in Britain.

At an innovation workshop in 2018, Network Rail's principal mining engineer Neal Rushton found himself seated at a table with electronics experts and robot researchers. He sketched a simple drawing of the sort of device he was looking for - something that could travel down a 15cm borehole, enter an underground cave and map its interior.

Existing methods of mapping these areas are slow and sometimes hazardous. Surveyors either drill multiple boreholes into the ground, through which they poke sensors at the end of long sticks in order to scan the space below; or technicians enter the mine shafts and caverns themselves to collect the data by hand. Dangerous gases, cave-ins and even explosions are all possible causes of harm to such workers.

Robotics engineer Simon Watson came up with a folding design for the drone

When Simon Watson, a robotics engineer at the University of Manchester, saw Mr Rushton's drawing, he immediately piped up: "Eh, I've watched a film about that," he said. "It's Prometheus."

In a well-known scene, external in the science-fiction blockbuster, four spherical drones whizz off into a creepy, unexplored alien structure, scanning it with lasers as they go in order to build up a 3D model of the environment. It's a tantalising moment in which the human space travellers realise the enormous scale of the outlandish place they have stumbled upon.

Mr Rushton knew the film and so instantly recognised Mr Watson's analogy, which got everyone at the table talking. "A tool like that would be invaluable," says Mr Rushton today. "Not just for us but for hundreds of applications around the world."

This is how the "Prometheus" drone project got its name and, although the caverns Network Rail hopes to explore with the device will be smaller than the alien tunnels in the film, the technological principles are almost exactly the same.

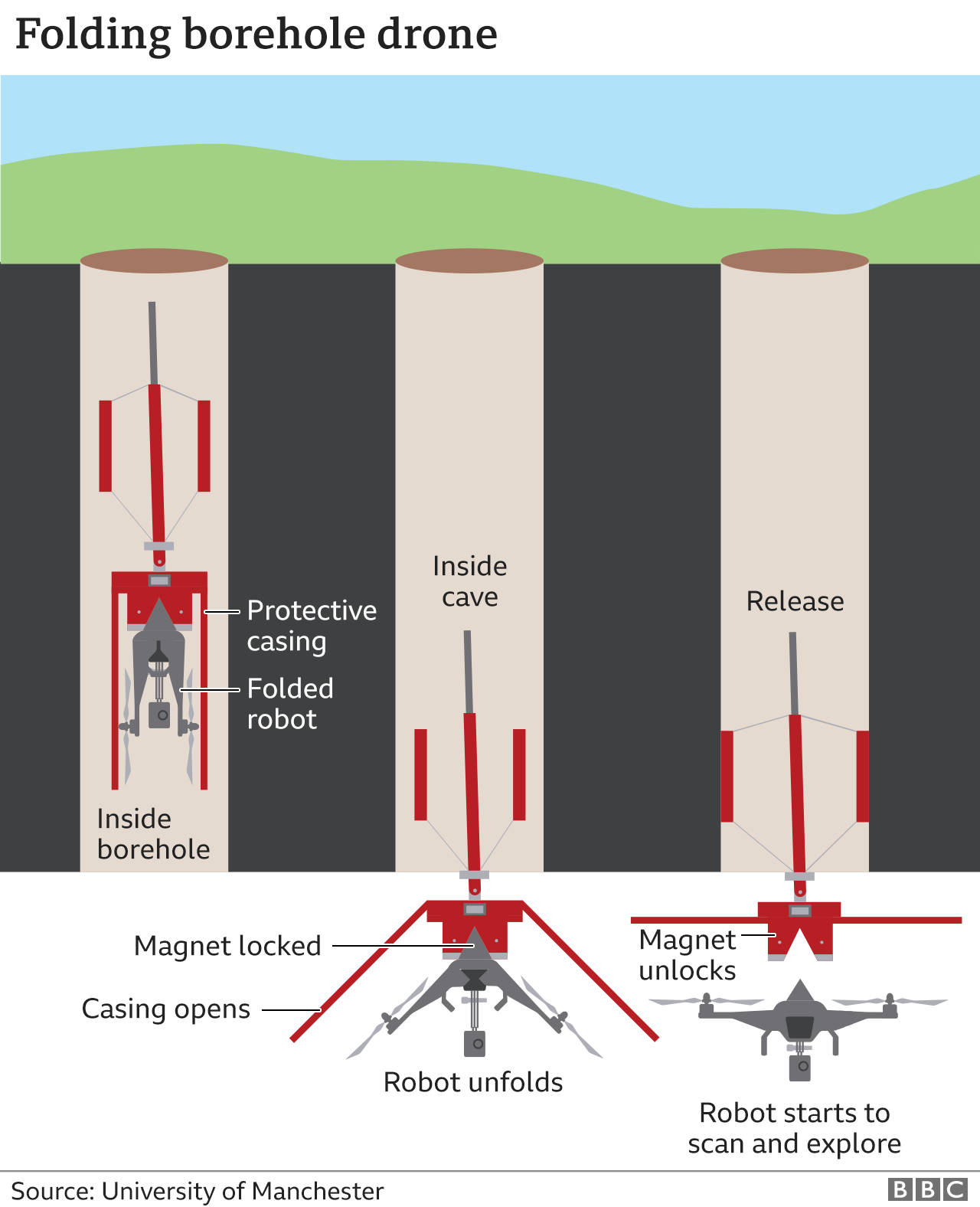

There are special challenges though. For one thing, the drone has to fit through a snug 15cm (6in) borehole - a standard size used for underground surveys. Mr Watson, his research associate, Liam Brown, and colleagues have come up with a folding design in which the drone's propeller-equipped arms raise up into the "flight" position once the device has been pushed through the borehole and into the gloomy mine below.

At that point, the drone detaches and zooms off into the underground space on its mission. But no human will have control over where it goes because of the lack of light and difficulty of maintaining a wireless signal to the surface. Prometheus must instead explore the subterranean space autonomously.

To gather data about its environment and avoid slamming into cave walls or stalactites, the drone will carry a camera that uses lasers and infrared imaging to make 3D maps of its environment. The device has been miniaturised so that it can fit onto the drone. If all goes as planned, once it has acquired a map of the cave's interior, the drone will then fly back to the borehole where it will autonomously dock with a rig and be pulled back up to the surface.

The consortium behind the project involves various organisations, including - among others - the universities of Manchester, Bristol and Royal Holloway, all working on the drone itself; and Headlight AI, a London-based tech firm tasked with designing the special camera and other components.

"The challenge with the Prometheus drone is, number one, it has to navigate when there's no GPS," explains Puneet Chhabra, co-founder and chief technical officer at Headlight AI, who was present when the idea for the Prometheus project arose at the innovation lab meeting in 2018. "That means you have to create a 3D map and that map has to update itself as the drone moves - you have to localise in that space, if you like."

Jameel Marafie and Puneet Chhabra (right), co-founders of Headlight AI

Not only that, but because of the drone's diminutive size, it can carry only a small battery so will have to complete its mission in just 10 minutes, says Mr Watson: "You have to navigate quite quickly but also slow enough to gather up all the data."

The team has already trialled some of the technology during test flights, such as the docking equipment - which uses locking pins and magnets to hold the drone in place until it is ready to drop down and fly away - and 3D mapping. Their work is described in a recently published scientific paper, external.

Plus, Mr Watson and his colleagues have also tested some off-the-shelf drones, which unlike the completed Prometheus, can't fly by themselves and don't have scanning equipment.

Nevertheless, the experiments in caves in Shropshire gave the team a sense of how the devices cope with turbulence in confined spaces. It's important to account for this, because, should the actual Prometheus drone crash underground on one of its future expeditions, there's more or less zero chance that engineers will be able to retrieve it.

An in-cave flight test using a prototype of Prometheus itself is scheduled for spring 2021, says Mr Chhabra.

It's not the first time that someone has attempted to build an autonomous, cave-mapping drone. Three years ago, a team in Australia demonstrated one such device - though it was much larger than Prometheus will be.

Guido de Croon develops drones at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands

Meanwhile, Guido de Croon, at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, and colleagues, have experimented with a swarm of small, autonomous drones designed to map an unknown environment. Their research was published in the journal Science Robotics, external last year.

Prof de Croon says Network Rail's ambition is impressive.

"I think it's very exciting. I was not aware of this problem, I must say," he comments.

"There's a whole world underneath that's hardly accessible, and dangerous for humans."

Although the project presents multiple challenges, he praises the approach chosen by the Prometheus team. And he notes how discussion of Ridley Scott's film has also come up among his students while working on similar projects.

These drones can operate as a swarm

"Movies make people dream," says Prof de Croon. "Researchers, they have an eye out for this kind of cool stuff that they would like to realise in reality.

"It also works the other way round. Some of the research work you do inspires movie-makers."

All well and good, so long as Prometheus doesn't find anything too startling on its future missions - alien spawn lurking beneath the East Coast Main Line, for instance.

"It's when we find the cavern and it's full of eggs and we're like… erm, right," says Mr Watson, with a nervous laugh.