New aircraft spy opportunities amid aerospace woes

- Published

Vertical Aerospace is testing technology on its Seraph aircraft

Michael Cervenka traces his interest in engineering back to his grandfather's influence.

"He was an organ builder and had me sorting out screws on his workshop floor when I was 18 months old," he says.

That interest literally took off. He is now the boss of Bristol-based Vertical Aerospace, and has progressed to electric vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) machines.

With the potential to be quiet and economical, these aircraft have been touted as the next big thing in passenger aircraft.

Vertical is working on the VA-1X, an aircraft intended to fly between regions. That regional emphasis matters as eVTOL machines have often been promoted as air taxis, whizzing around our cities under the banner of "urban air mobility" (UAM).

Michael Cervenka says pilot-free aircraft are a long way off

Some even suggest these vehicles could scoop up passengers and whisk them along pre-arranged flight corridors without a pilot.

Vertical dismisses this as a fantasy. "Our aircraft will be heavily automated," says Mr Cervenka. "But both regulations and the public will require a pilot for years to come."

An automatic response to an obstruction on a landing pad below will pull VA-1X up and away from a collision, but people still want to see a highly trained aviator in charge of their flight.

Using multiple propellers that point skywards for take-off and then rotate to tilt forward to fly horizontally, the VA-1X aims to carry four passengers and a pilot over short distances more cheaply than a helicopter.

Multiple rotors are a safety feature on many eVTOL aircraft

Airlines operate within a framework of strict regulation, so how will this entirely new category of machine pass the scrutiny of international safety bodies? Mr Cervenka says he is working closely with UK and European regulators.

The technology behind VA-1X has been tested at a remote airfield in Wales using a prototype called Seraph. This is a piloted black box surrounded by six arms mounting rotor blades.

Seraph's chunky appearance belies its role in proving the systems that should keep VA-1X's eight electric motors pointing in the right direction. And if a motor fails Seraph can still hover and land.

With a winged design, as opposed to some of the wingless flying car proposals in the eVTOL world, Vertical's VA-1X gains lift. So the wings take pressure off its electric power source, which is derived from a car battery. Vertical employs 25 ex-Formula 1 engineers and a battery engineer from Jaguar Land Rover.

Electric motors are simpler and quieter than engines on helicopters or jet aircraft

The company claims its aircraft will be 30 times quieter than a helicopter. So in theory it should be able to make more use of existing heliports where the frequency of landings is restricted by noise regulations.

It spies a market for travel between locations not served by high-speed rail networks and regional airlines. Regional connectivity is the name of this game.

"We will offer an ability to connect places that are not well connected today," says Mr Cervenka, who is eyeing up a London-to-Brighton service, a route notorious for rail delays and traffic jams.

Covid has slashed airline passenger numbers. So Mr Cervenka reckons new purchases of large airliners are off the menu. But airlines might use eVTOL flights from a major airport into the centre of a city to attract business or first-class flyers as part of their fare.

The 150mph (240km/h) VA-1X will need a full battery recharge every 100 miles, but a 25-mile short hop from an airport to city centre would allow for a fast recharge and quick turnaround.

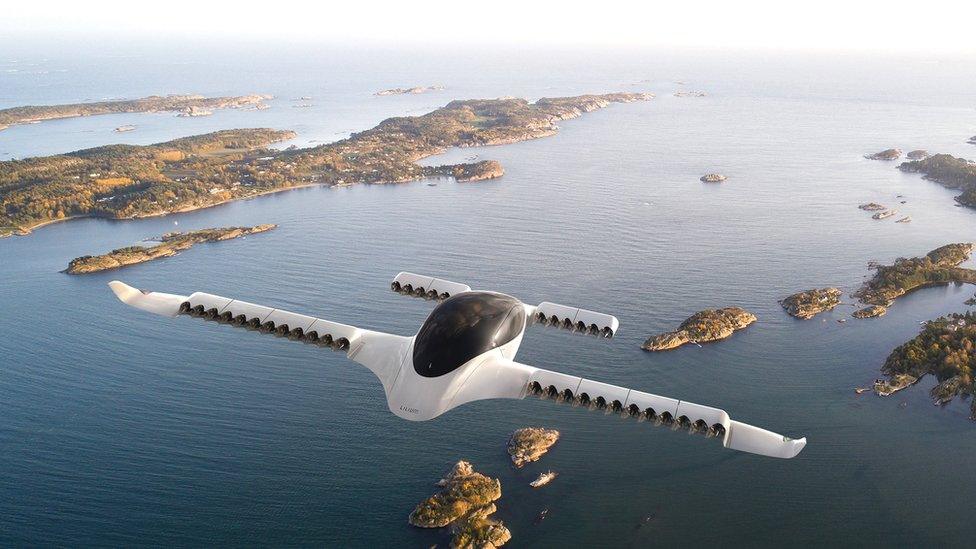

Lilium's aircraft demonstrates its vertical take-off capabilities

David Tait, a lawyer studying emerging technologies for the UK's Civil Aviation Authority, says he expects eVTOL craft to gain regulatory approval for certain services - but he also pours cold water on the wilder promises of flying taxis.

"Consumer on-demand services are a long way away," he says, citing the air traffic management challenges of putting too many machines into the air above a major city.

Designs such as the octo-engined VA-1X have no single point of failure, unlike a helicopter where the loss of rotor blades or power can be catastrophic.

"Our view is that eVTOL should be at least as safe as existing vehicles," Mr Tait says. "Our expectation is that these will be quieter, cleaner and safer."

Lilium has attracted engineers from Boeing and Airbus

Approximately 300 eVTOL projects are under way around the globe and Germany's Lilium is one of the most advanced, attracting engineers from Boeing and Airbus.

Its distinctive eVTOL machine has 36 electric engines buried inside slender white wings and tail planes. These are ducted fans, sucking in air and blowing it out in the manner of a jet engine but without mixing it up with fuel. This mass of fans creates a strong current that will push the little five-seater jet to 300km/h (186mph) and give the pilot control over direction.

Remo Gerber, its operational chief, says that despite this radical design Lilium is "following a classic aviation approach", with safety dictating design features such as the Kevlar shell around the fan blades, ensuring that if a blade flies off it will be contained within the tough material.

A technology demonstrator flew at its base outside Munich in 2019 and the larger production machine is intended to carry four passengers and a pilot like the VA-1X. These light passenger loads reflect the power limitations of electric motors.

Mr Gerber shares the view that UAM has been oversold: "We struggle with UAM. We don't see the benefits." He argues that very short distances make no sense for eVTOL because the final section of the trip still has to be made by road - Lilium is also focussing on the regional transport market.

Lilium is betting on longer-range regional connections

Lilium plans a regional network based around Dusseldorf and Cologne airports in Germany's densely populated North Rhine-Westphalia area. The idea is to connect smaller cities such as Aachen and Munster to the airports via Lilium aircraft by 2025.

It is also designing eVTOL airports - what it calls "vertiports". With a relatively small footprint these present an affordable alternative to airports and railway stations. These could link up a region with hundreds of daily flights, and multiple high-frequency flights from different locations would carry more passengers than rival first-class rail services at equivalent fares.

Back at Vertical, manufacturing will see components such as the VA-1X's cockpit displays arriving to be integrated in a final assembly. So Mr Cervenka's very early experience putting many parts of a machine together may still pay dividends.