Will the UK really refuse trade deals over human rights?

- Published

The UK is forging its post-Brexit path as a "confident, independent nation - and an energetic force for good", according to the government.

It's free to set trade on its own terms, pursue opportunities and higher living standards. But can it square profit with principle?

Is turning a blind eye to human rights violations worth it to have a trade deal that knocks a couple of quid off the price of an imported shirt?

That New Year's resolution is already being tested, as China falls increasingly out of favour.

Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab has referred to conditions, under which over a million Uighur Muslims are being held in camps and forced into work, as "at the worst... torture and inhumane and degrading treatments".

He warned that British companies will face fines, if they can't show that their supply chains are free from forced labour.

In December, a BBC investigation revealed thousands of Uighurs and other minorities have been compelled to toil in the cotton fields of Xinjiang. The region accounts for a fifth of the world's crop - it's not always easy to tell where your t-shirt hails from.

The UK and Canada have led the charge here, but one wonders how much further can it go.

Mr Raab told the BBC that the UK should not be engaging in free trade negotiations with countries whose record was "well below the level of genocide".

Determining human rights abuses

There are several issues with this: first, working out who gets to decree human rights abuses.

Amendments to the Trade Bill currently going through Parliament would oblige the government to assess the human rights records of potential partners.

In July, Dominic Raab accused China of "gross and egregious" human rights abuses against its Uighur population

One amendment proposes allowing the High Court to declare a genocide in other countries, and forcing the immediate cancellation of trade deals with said nations.

Mr Raab, however, says the decision to declare a genocide can't, and shouldn't be, delegated to the courts. Rather, it's for MPs to hold the government to account over trade deals.

But Labour MPs, who have written to their Conservative counterparts urging them to support the amendments, say they've already been denied powers of scrutiny.

They highlight trade deals rolled over with Egypt, Cameroon and Turkey, with whom the UK previously enjoyed similar deals the EU had struck.

These three countries, they argue, have questionable records on human rights.

And then there's China. The UK is not planning a deal with Beijing and has indicated it won't do a deal with countries that don't share its democratic values.

But both nations have their eye on joining the wider Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement.

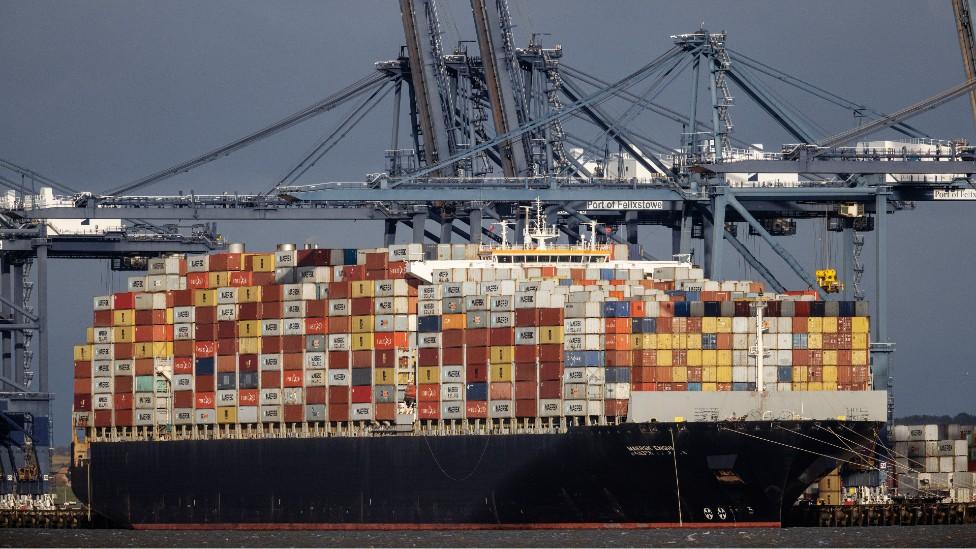

With imports and exports worth almost £80bn in 2019, China already scores as one of the UK's largest trading partners, and it's not just about frocks and financial services crossing borders.

The question of China

Since Xi Jinping and David Cameron famously sipped a pint in a Buckinghamshire pub in 2015, Chinese investment in the UK has exploded, backing everything from football clubs to restaurant chains.

Now China's appeal has soured, but it may not be easy to back away from encouraging investment, or a trade deal which touts lower import prices and greater opportunities for exporters, when the UK economy is already reeling.

The Wolverhampton Wanderers are owned by Chinese investors Fosun International

Take textiles - a free trade deal would do away with a 12% tariff on clothes hailing from China. Ultimately, trade deals build on an existing - in this case very lucrative - relationship.

Critics argue it's not enough to refrain from boosting ties with nations with chequered records - they should be lessened.

But it's even harder to snub countries that are already providing jobs for thousands, or items from the frivolous, such as smartphones, to the vital, like billions of PPE items.

Some say the UK has its own issues elsewhere. It resumed the sales of arms to Saudi Arabia last year, after the government said the method for licensing had been reformulated to ensure they wouldn't be used in Yemen. Human rights groups are less sure.

Balancing its quest to be a responsible citizen, together with exploring fresh fortunes, is just one dilemma the UK faces, as it shapes its new identity on the global stage.

- Published9 December 2020

- Published26 January 2024