Like a good deal? Maybe a hagglebot can help

- Published

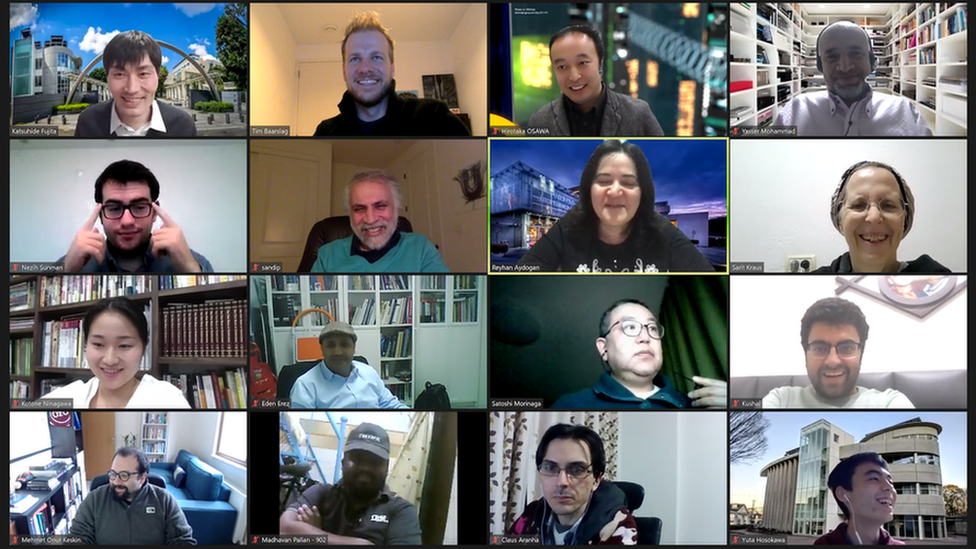

Participants in the 2021 hagglebot games

Earlier this month, the Olympics for hagglebots was held: the 11th annual competition for artificial intelligence (AI) that has been trained to negotiate.

Called the Automated Negotiating Agent Competition, it pits more than 100 participants from Japan, France, Israel, Turkey and the United States against one another, in five leagues.

This would have been held in person (or in silicon) in Japan, as part of the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, but due to coronavirus the competition was part of a virtual conference.

Universities from Turkey and Japan were the big winners this year, haggling with humans and each other: simulating a factory manager doing supply chain management, and the game Werewolf.

In some leagues they haggle with real-life human subjects, recruited from the web. In others, the bots negotiate with other bots.

"In the first years, [the AI] were really easily outperformed by human beings," says the hagglebot games' co-founder, Tim Baarslag from the Centrum Wiskunde & Informatica, the Dutch national research institute for mathematics and computer science.

But now they are "behaving closer to human form, sometimes even better than humans but only in very artificial domains," he says.

Tim Baarslag says that AI is getting close to matching human negotiators in some situations

Humans have the upper hand understanding emotion and subject matter expertise, but can falter when there are many issues.

Negotiating software has quite a long history - a few negotiating support systems started appearing in the early 1980s: tools with names like Inspire and Negoisst.

These drew on academic work in game theory, which models how rational decision makers make choices, based on views about what other decision makers will do.

The tools tried to help negotiators prepare offers and strategies, and then help both sides arrive at good deals that "don't leave money on the table", says Mr Baarslag.

But now horse-trading artificial intelligence that can act on its own has begun appearing in business.

If you sell to Walmart, you might have already met one. An AI system developed by Pactum was tested by the giant US retailer.

A chatbot contacts suppliers, and invites them to renegotiate together contracts over things like price and payment terms.

With some suppliers there are up to 30 different points to settle.

Pactum chief executive Martin Rand has been testing the firm's AI at Walmart

"We now see that some vendors prefer talking to a bot. If there are tens of thousands of vendors, it's hard to get human attention sometimes," says Martin Rand, chief executive of Pactum, which is based in Tallinn and Silicon Valley.

This bot often proposes unrelated offers to a vendor, asking for instance if they would rather increase their payment time by a certain number of days, or keep items in their own warehouse.

Then based on these answers the bot learns their preferences, Mr Rand explains.

If everything is known, "negotiations should not have to happen at all. You need zero rounds, and the deal is struck immediately," says Mr Baarslag.

Much of negotiation is finding out which subjects matter more to your counterpart, and at what point they'd walk away.

Machine learning now helps an AI predict the other side's preferences based on a few observations, plus lots of experience in prior negotiations.

And once you know these things, even a negotiation involving thousands of side deals "just becomes a big calculation, something computers are amazingly good at", according to Mr Baarslag.

"We had a problem at BP. It was taking us 90 to 120 days to get a contract done," says Michael O'Brien, who managed the oil company's $2bn (£1.5bn) budget for IT services from 2012 to 2020.

Mr O'Brien found his department was spending 80% of its time negotiating terms and conditions from scratch with its vendor.

Only 20% of the time was spent sorting out the most difficult points, such as disputes over the quality of goods and services.

Michael O'Brien introduced AI to deal with IT contracts at oil giant BP

With thousands of bespoke contracts in place, there was no way to know how often suppliers just agreed to the standard terms, or to ones that were heavily negotiated.

There were 1,400 vendors. "I couldn't read 1,400 contracts," Mr O'Brien says.

Contracts would "go into a file cabinet, and I couldn't remember what we agreed to," he says.

The company may always have asked its contractors to have $10m in insurance for a $10,000 project, then often settled on a tenth of that.

So he made a machine-learning tool together with AI developer App Orchid that could learn what BP actually agreed to in past contracts.

And the tool can use that information to offer more informed options to suppliers it negotiates with.

The idea suppliers could negotiate with an AI and get to a contract with less time and effort was revolutionary, says Mr O'Brien.

Suppliers said to him: "If you're telling me if I select this option, which isn't great for me but isn't necessarily bad, we can have a contract tomorrow - well I'm going to click that, and let's be done with it," he says.

It resulted in an 80% reduction in work, with contracts taking between one and eight days to negotiate.

In August 2020, this tool, ContractAI, was spun off for anyone to use.

One challenge has been getting the AI to understand the legal training language in previous contracts, but then use accessible language with its negotiating partners, says Mr O'Brien, now ContractAI's head.

While some people are working on automated negotiation, between two bots or a bot and a human, others are crafting negotiation support systems - an AI helping two or more humans.

Jared Curhan says AI will be a useful adviser during negotiations

Machine learning helps us learn to recognise when negotiations are going well or badly, says Jared Curhan, who is faculty director of MIT's negotiation for executives programme.

An AI listening by microphone to the first five minutes of a negotiation can predict 30% of the variation in its eventual outcome, just from negotiators' voices.

This research could produce AIs "as an adviser on your shoulder, whispering in your ear, 'I think they're lying, you should push harder,'" says Johnathan Mell from the University of Central Florida.

"I can also see AIs working as your agent, not just as an adviser - really doing the negotiating work for you, in the future," adds Dr Mell, who built a system called IAGO to create bots that negotiate for you.

When negotiators' volume and pitch vary a lot, it turns out, they're performing less well at the table.

If they mirror each other's speaking patterns - say, both using short utterances like "uh huh" - the weaker party is getting on well.

Inexperienced negotiators don't like when their heart rate goes up; seasoned pros do better when theirs do.

AI is "providing a mechanism by which we can understand these relationships better than if we just had humans looking at the data," says Prof Curhan.