What's your pension invested in?

- Published

Perhaps during lockdown, you've been tempted to do some financial spring cleaning and checked in on a private pension. But do you know what companies you're actually investing in?

If you do, you are probably in a minority, according to Simon Harrington, senior policy adviser at the PIMFA, the trade association for firms that provide investment management and financial advice.

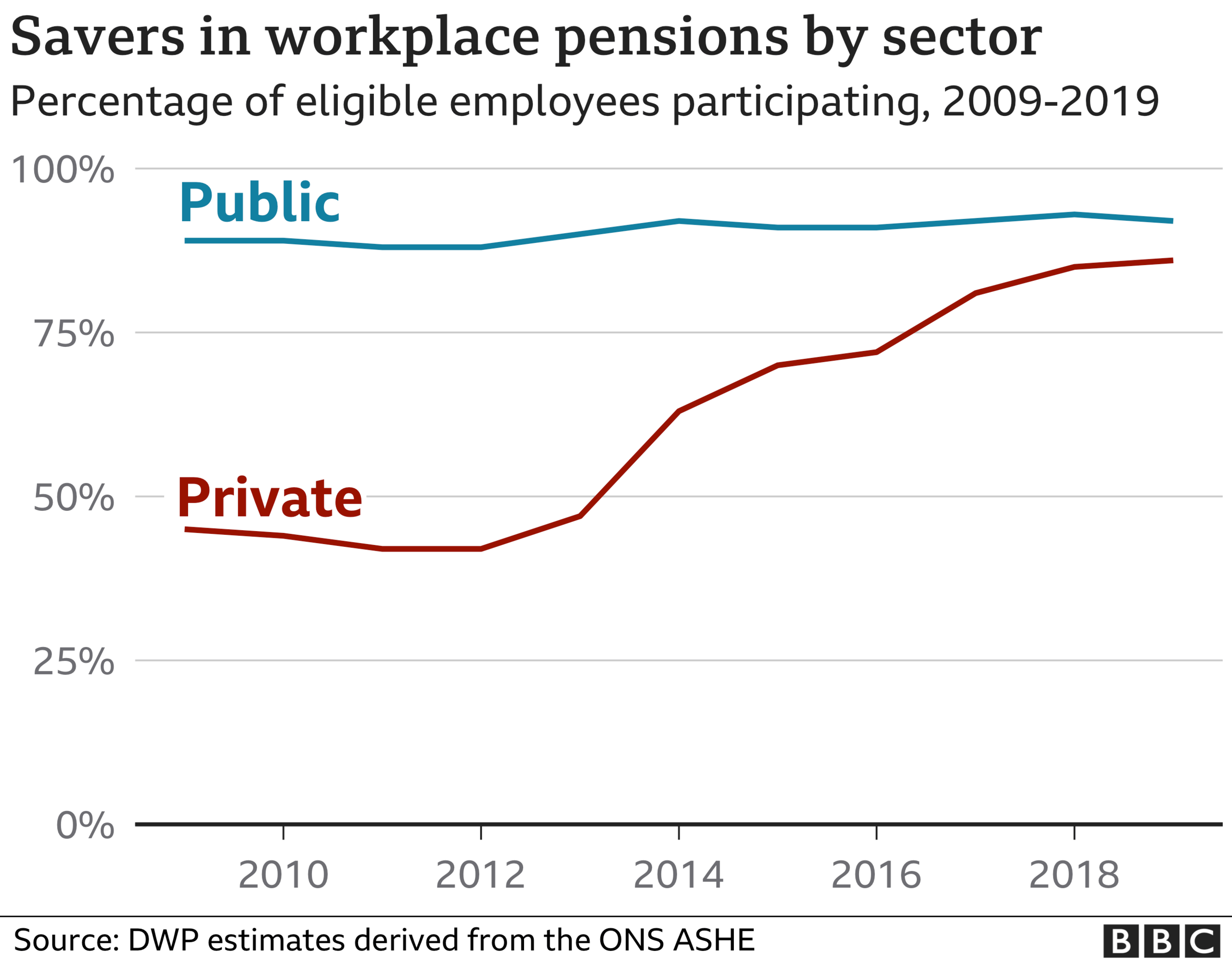

Part of it is to do with automatic enrolment. Since 2012, workers in most companies have been automatically signed up to a workplace pension without having to lift a finger.

This has swelled the number of people with a workplace pension by about 8.5 million to 19.2 million.

"The whole point of automatic enrolment is that basically, people save up [by] doing nothing at all," says Mr Harrington.

"People will know, in most cases by looking at their pay every month that some money has gone into a pension scheme. But all of the data that we have suggests that they really never log on, check their annual benefit statement, or have any idea of what it is that they're invested in."

This isn't a disaster, he says. The default fund into which their money is placed is generally cheap to manage and receives a lot of attention because of its size.

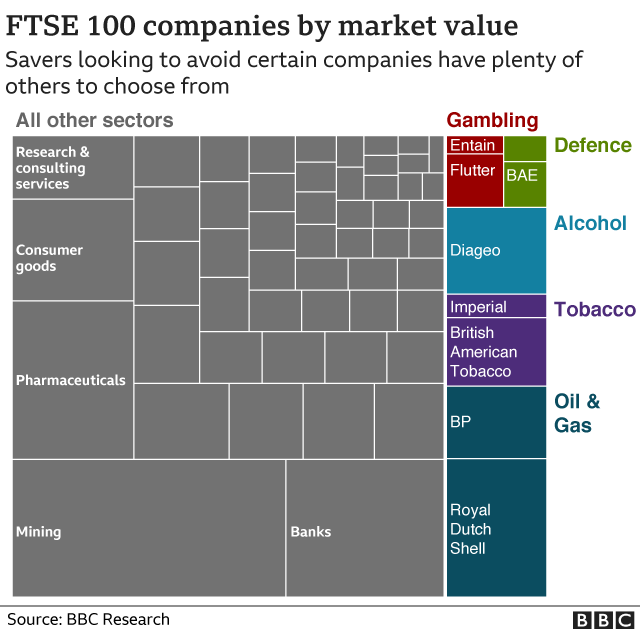

But it means that many people are invested in a pot of very disparate interests, which may include tobacco, gambling, firearms, alcohol, oil or other investments that they may personally want to avoid.

Part of that is down to the rules for this large pool of pensions. A default fund - the one your money is invested in if you take no action - can only charge a maximum of 0.75% a year, which means a lot of it will follow stock indexes like London's FTSE 100, FTSE 250 or the S&P 500 in the US - so-called passive investments which will include a vast number of companies.

Ethical funds, which avoid investing in these companies, do exist, though, and they are growing in popularity, albeit from a low base.

Stockbroker Hargreaves Lansdown, one of the largest do-it-yourself investment platforms, says the number of ethical funds it offers has almost tripled in the past 12 months, and there's more than 11 times more money in these funds than a year ago.

There are now close to 200 such funds, but that's out of 3,500 funds on the platform overall.

Simon Harrington says more interest in what people are invested in will follow

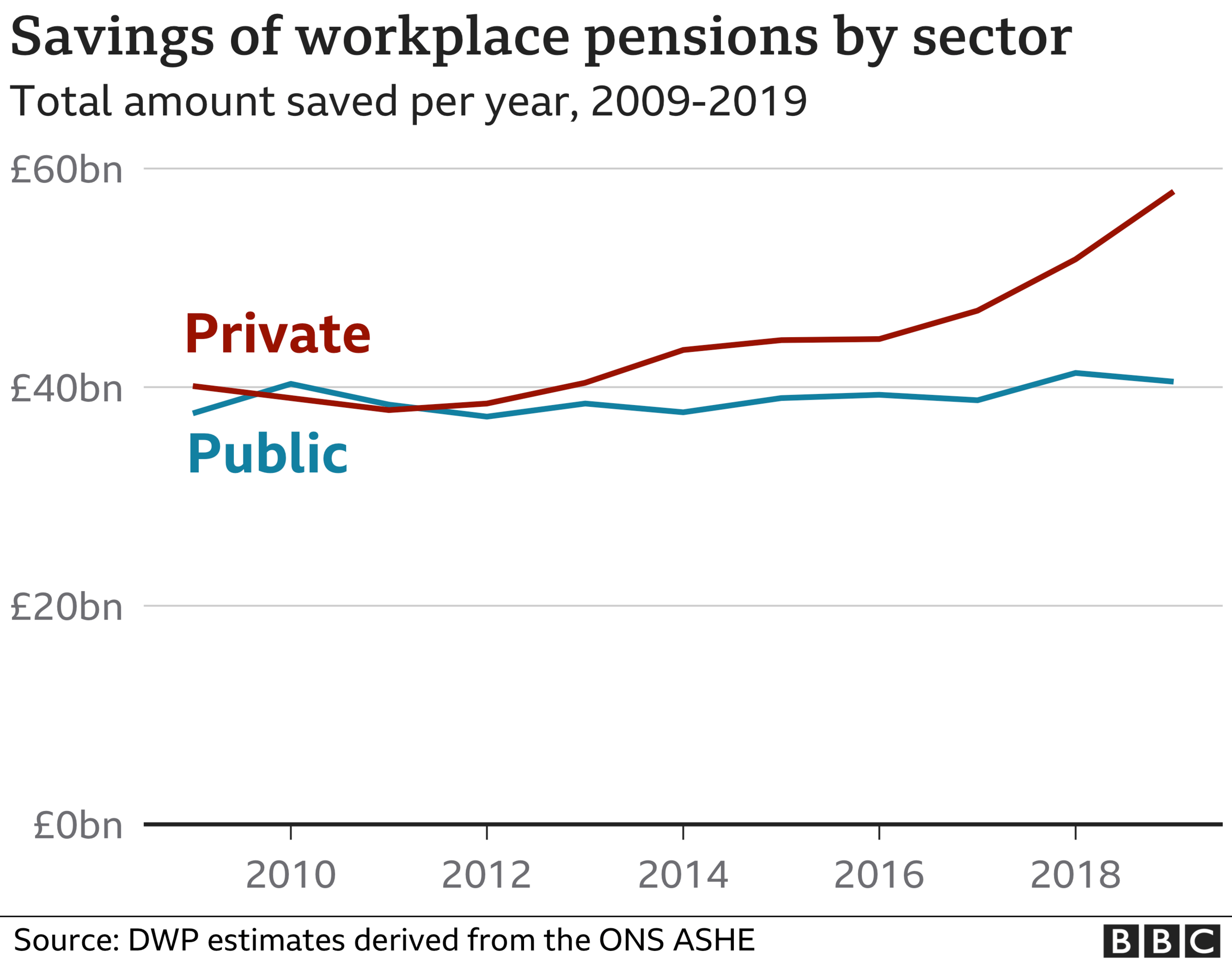

Pension providers are taking action, though. The biggest by membership is Nest, which has 9.8 million members and oversees £16.5bn of savings. It has already acted and scrubbed its investments of tobacco and uranium. It has a 10-year plan to cut emissions and wants companies it owns shares in to cut out Arctic drilling and coal.

Pension companies insist that there is interest in ethical investments.

The BBC asked some of the UK's largest pension providers how many workplace pension funds they offered and how many were ethical. Of the six that came back to us, we found that on average one ethical fund was offered for every 15 regular funds.

Several insist that all their investments now follow some pattern of green or ethical investing.

Legal & General Investment Management says all its default investments avoid controversial weapons and companies that purely mine coal.

Aegon says half of pension savings using its default fund will soon be in ethical investments and that it plans to slash carbon emissions in its investments.

Aviva says it has set a target for its default fund to be carbon neutral by 2050. It wants regulators to force its competitors to do the same.

A challenge for savers is that there's no agreed-upon definition for what qualifies for an ethical investment. And switching to an ethical fund may not provide the best financial returns.

Another challenge is finding those cheap funds which track an index, says Hector McNeil, co-chief executive of European investment platform HANetf.

While there are cheap international funds which exclude tobacco, external, for instance, such funds are harder to come by in the UK.

Much more choice and customisation is likely to be available in the future, he says.

"I think in three years' time we're going to be talking a totally different story," he says. He thinks most products will eventually allow customers to veto certain industries at will.

Hector McNeil says more customisable investments are on the horizon

Mr McNeil's company has grown from managing $50m (£35m) to $2.25bn (£1.6bn) in a little over a year. It designs funds and rose to prominence with a tradable fund investing in gold.

"You're getting more, broader, products," he says.

Many of his funds are based around themes, such as ethical gold or medicinal cannabis, or removing carbon,

If you take a look at the funds in your pension you may find it hard to tell where the money is. Many funds only list their 10 largest investments, leaving the majority of the value unaccounted for. Unless it explicitly promises to avoid a certain investment, it could be lurking in there.

With funds like his, which can be traded on stock exchanges, all investments are listed, he says, making it easy to check where your money is held.

Even then, mistakes are made. In 2019, fund manager Vanguard accidentally invested in gun-maker Sturm Ruger, external for a month before correcting the mistake.

Despite the challenges and the inertia of some savers PIMFA's Simon Harrington is upbeat about ethical investing.

"The UK pension saving population is reasonably young," he says.

Before workers were automatically added to workplace schemes, "the number of people actively saving into a pension scheme was very, very small," he says. "And we have to be realistic about the fact that we're at the start of a journey to a more developed saving culture."

The demand for ethical investments in personal savings like individual savings accounts (Isas) is a good indicator for what may be to come, he says.

Related topics

- Published31 December 2020