Why have global stock markets gone up this year?

- Published

Around the world, millions of people have lost their jobs or been paid by their governments to stay at home.

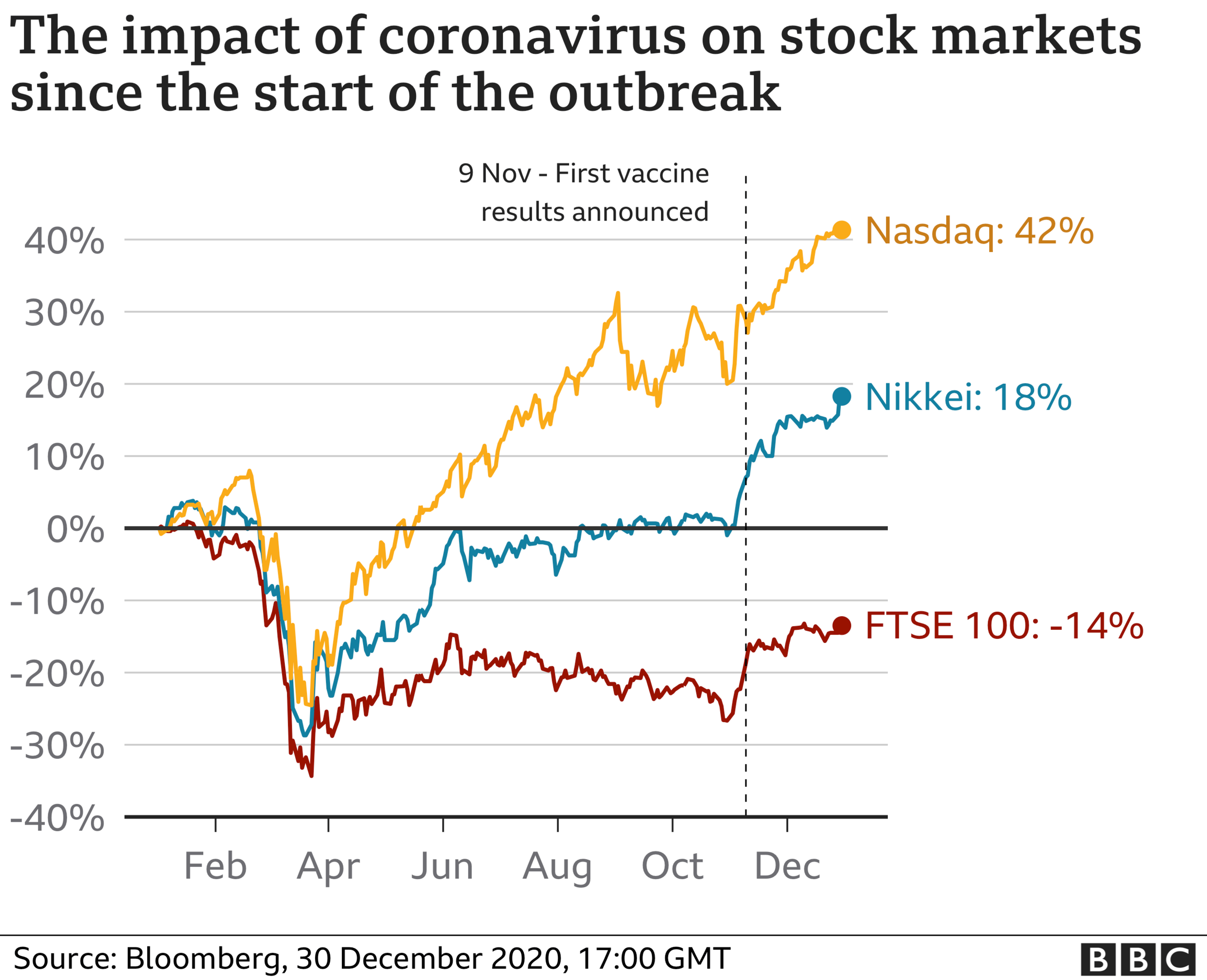

Yet stock markets have bounced back from steep drops in March.

The most striking gains have been made in the US, with the tech-heavy Nasdaq up a whopping 42% and the wider S&P 500 up 15% on the year.

But the UK's FTSE 100, with its struggling oil companies, banks and airlines, all of which were whacked by the pandemic, has not had such an easy time.

While it is still down 14% since the start of the year, it has seen a steady rise over the last few months and received a recent boost after a trade deal with the EU was reached and another vaccine was approved.

In Japan, shares bounced back after a vaccine was found, with pharmaceutical stocks and gaming companies leading the way., external

Some of the growth is down to the way we measure the performance of stock markets, and some might be down to some overenthusiasm, according to investors.

There is also the matter of the amount of money central banks are creating, they say. And finally, there are some small reasons for optimism.

An important thing to consider is that stock market prices aren't just about the here and now, says Sue Noffke, head of UK equities at money manager Schroders.

"Stock markets look forward so they are a bit like driving a car - you have your eyes on the horizon, rather than the pothole that's in front of you," she says.

Investors are banking on the success of the various new vaccines that have been approved or are in development in getting growth and sales back to normal.

Cheap money

They are also factoring in cheap borrowing, which is a boon for businesses.

There is also all the money being created by central banks, and the effect that is having. The Bank of England alone, external plans to buy £895bn of government and corporate bonds with new money, via quantitative easing (QE).

Since March the US Fed has bought more than $3 trillion (£2.25tn) of assets.

These purchases are part of an effort to keep borrowing costs low, and while this new money enters the economy as purchased bonds, it has the effect of driving up prices elsewhere.

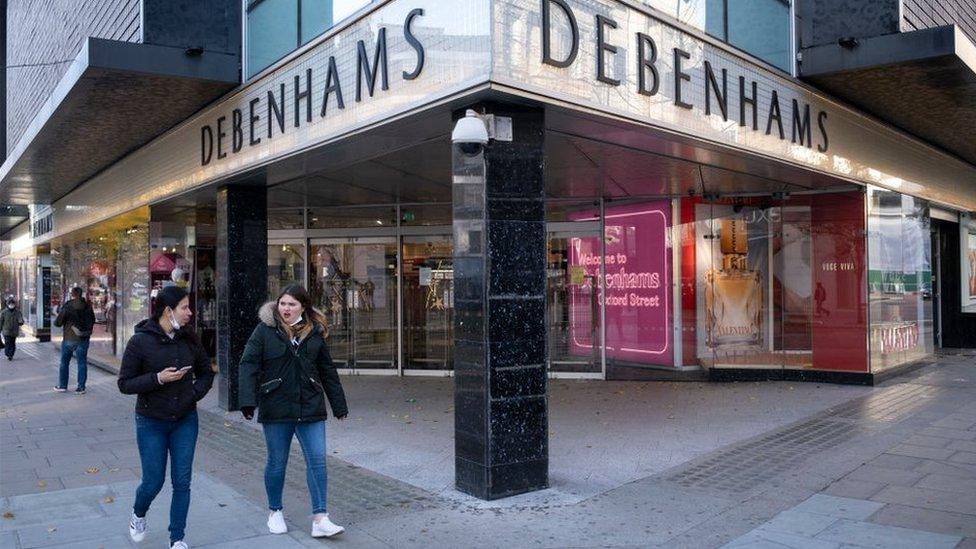

While the FTSE 100 in London has risen since March, chains like Debenhams have collapsed

"Money has become cheaper, and cheaper money boosts the valuations of financial assets and that is what we have seen globally supporting the stock market," says Ms Noffke.

Five dominate

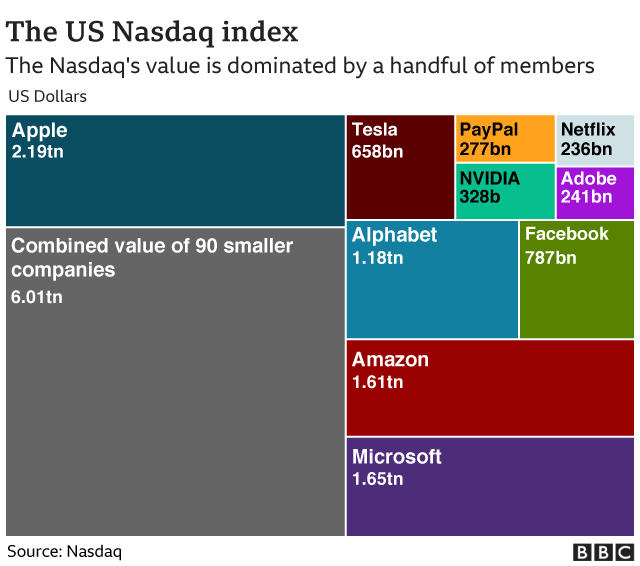

When we look at the performance of markets, we are typically looking at an index, which is a group of companies lumped together.

The growth - or otherwise - of large companies has a bigger effect on the index's value than the movements of smaller ones.

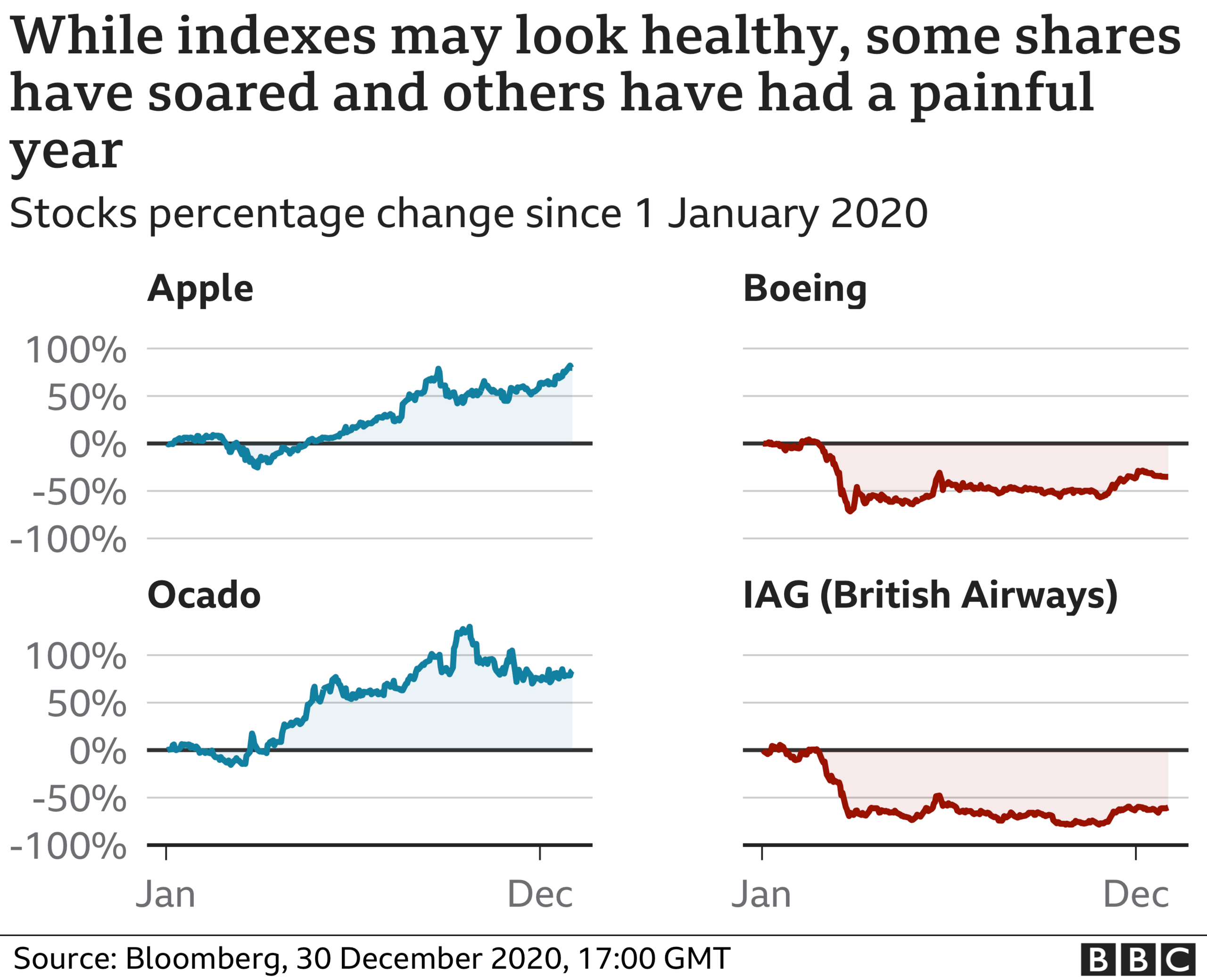

But of late, especially in the US, the larger ones have become very, very large. This means that a good year for tech companies, whose earnings have grown as more people work remotely, has masked a bad year for firms like airlines.

The Nasdaq, for instance, has seen a huge rise since the start of the year. But just five companies - Google owner Alphabet, Apple, Microsoft, Amazon and Facebook - have almost the same value as the remaining 95 combined.

"So you look at the performance of the index, and you would think that coronavirus had not really impacted the US economy at all," says Ms Noffke. "And that's clearly not the case. So it's not necessarily representative."

10-year trend

The dominance of a few big companies in an index has coincided with the rise of so-called passive investing, where pensioners, money managers and speculators can buy a cheap investment fund that tracks an index.

Hence, when investors buy these funds, they buy the underlying shares and help give prices a boost.

"What you can see for the last 10 years is an outflow of money from active funds into passive funds and that didn't change with the pandemic," says Johannes Petry, a post-doctoral researcher in financial markets at the University of Warwick.

He says the companies that oversee these indexes, which companies go in them, and therefore which ones benefit when someone invests in a FTSE 100 fund or Nasdaq fund, have growing power because of this.

While many companies join an index or leave it because of their size, this is not always the case, and index setters' rules can mean that big companies, like online retailer Boohoo for instance, aren't part of large indexes like the FTSE 100.

For example, he says, electric car maker Tesla, which entered the S&P 500 index this month, is estimated to have generated an extra $100bn of demand for its shares as funds scramble to buy them.

Nervous?

That being said, things might be ready for a drop, says Joe Saluzzi, a partner at brokerage firm Themis Trading.

"Every day is a rally and everyone's shaking their heads," he says. While plenty of investors think that markets can't keep rising forever, it's hard to tell when a drop will come.

He says he watches an indicator published by CNN called the Fear & Greed index, external. It was as high as 92 a month ago, indicating "extreme greed", although it has since fallen.

"When I see that it tells me people aren't really nervous and they should be," says Mr Saluzzi.

Surging markets seem out of place with rising unemployment and damaged economies

Another pointer he watches is the ratio of bets that the market will rise compared to bets that it will fall. Recently, rising bets outweighed falling bets by the most since 2012, external.

"A big mistake people make is they go through the analysis we just did, we come to the conclusion that we are priced too high, I have to get out," he says. "They say, 'But I'm smarter than the market.' No you're not. Nobody is."

There are a few reasons for markets to carry on their run, says Ms Noffke, at least for a while.

Plenty of people who have kept their jobs have been spending much less and will want to have some fun and make some purchases once they can, she says.

Governments are unlikely to return to the austerity measures seen in the wake of the last crisis, she adds.

But when markets do drop, it will be interesting to see how investors react, says Mr Saluzzi, especially younger ones who have mainly experienced a market that goes up and recovers quickly. They are a small but active part of the market.

"They are not battle-tested. They haven't been in the markets that long," he says. "It gets ugly quick."

- Published16 December 2020

- Published17 December 2020